Editor's Note

This is one of a series of guest posts we are running at the USIH blog this week to reflect on the scholarly legacy of Alan Trachtenberg, a Yale professor and pioneering thinker in the field of American Studies. Trachtenberg passed away on August 18 at the age of 88.

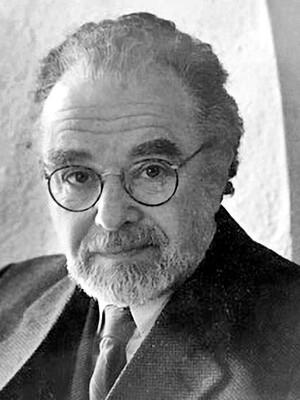

Alan Trachtenberg / Yale News Service

The passing of Alan Trachtenberg on 18 August was an occasion for great sadness for those of us who had learned so much from him over the years, and of course even greater sadness for his colleagues, family members, and friends. Alan’s work was absolutely crucial to my own intellectual formation, and he himself was enormously generous to me when it mattered. I identified, and I suppose still identify, strongly with the neo-Marxist turn in American Studies in which he played such an important role. Alan showed us you could write a “critical cultural history” of ideas, visual culture, literature, and the built environment, and do so in graceful and accessible prose. He was a literary artist in his own right.

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to reflect on Alan’s work at a roundtable Ann Fabian organized at the 2005 American Studies Association meeting to mark the fortieth anniversary of the publication of his first book, Brooklyn Bridge: Fact and Symbol. Robin Kelsey, Elizabeth Blackmar, Brad Evans, and Richard Haw also participated, with Alan offering comments at the end. I reproduce my remarks below.

_____

ASA meeting, 4 November 20

For forty years now, Alan Trachtenberg has been building bridges. Bridges back to a moment in the cultural history of the United States when American nationality, the idea of a civic culture, and “the modern” were all more fluid than they have come to seem in retrospect, more amenable to popular strivings, cosmopolitan mixing, and democratic hope. Bridges built of myths, literary texts, public speeches, photographs, buildings, and, yes, bridges themselves. Those “structures of meaning and feeling,” as Alan has characterized his subject—with a nod to Raymond Williams—have connected the multiple enterprises of American Studies since the publication of his first book in 1965.

Of course, it has been one bridge above all others—Brooklyn Bridge, located in what Paul Rosenfeld called the Port of New York—that Alan has been building for some time now. By interrogating the lives and works of the Roeblings and their interpreters, Alan has himself joined in the making and remaking of that bridge’s meaning, intervening in the epic narratives that followed immediately upon its construction, and subjecting them to his uniquely demanding scrutiny. It is fitting that his most recent book, Shades of Hiawatha, takes us back to the Port of New York, where the Wannamaker Department Store sought to build an Indian Memorial monument as a partner to the Statue of Liberty, and where young Luther Standing Bear marched with his school band in the opening day ceremonies at Brooklyn Bridge. Even more fitting that he closes that book by invoking Standing Bear and Hart Crane together imagining “a humane nation as a great bridge woven of diverse tribal stories.”

One way of describing Alan’s bridge-building over the years is to call it “critical cultural history”—the phrase he himself used in a retrospective essay on The Incorporation of America. To my mind, there has been no better practitioner of critical cultural history working in American Studies, no one who has brought a deeper, more informed historical understanding to the study of expressive culture. There has likewise been no other scholar in the field who has more deftly deployed the word “culture” to chart a “whole way of life” shot through with political contradiction, to envision the totality of human relations and representations, and to maintain that culture, understood as a realm of alternative values, might prefigure a more fully democratic society. To be a critical cultural historian, from this perspective, is to write as an immanent critic of culture as it was understood and imagined at a particular moment, probing its fault lines and pushing hard to expand its borders of social possibility.

As I have read Alan’s work over the years, it is the critical dimension of his cultural history that has most inspired and astonished me. In those extraordinary books, one again and again finds sparkling gems of cultural criticism: his reading of Crane’s “The Bridge” in Brooklyn Bridge or of Melville’s “Billy Budd” in The Incorporation of America; his recovery in Reading American Photographs of what he calls the “political art of the photograph” in Walker Evans’s work; his juxtaposition of Longfellow, Robert Frost, and Lewis Henry Morgan in the opening pages of Shades of Hiawatha. Such passages could easily stand on their own as essays; they are models of critical writing that show up the foolishness of all dichotomies of “text” and “context,” “base” and “superstructure.” In these readings, context is folded into the very structure and form of texts, which themselves shape the felt and imagined world beyond.

To consider Alan as a cultural critic is likewise to appreciate his gifts as a literary stylist. Think, among many other passages, of the opening paragraph of Brooklyn Bridge:

Brooklyn Bridge belongs first to the eye. Viewed from Brooklyn Heights, it seems to frame the irregular lines of Manhattan. But across the river perspective changes: through the narrow streets of lower Manhattan and Chinatown, on Water Street or South Street, the structure looms above drab buildings. Fragments of tower or cable compel the eye. The view changes once again as one mounts the wooden walk of the bridge itself. It is a relief, an open space after dim, crowded streets.

This is a passage that stands alongside John Dos Passos’s “Camera Eye” vignettes in the USA trilogy, and in many ways, surpasses them.

It is as a cultural critic, in my view, that Alan has played his most important role as a bridge-builder within American Studies. No one else writing today has more effectively reinforced the historical connection between American Studies and the non-academic criticism that preceded it in the first decades of the last century. Again and again, his work makes its way back to the Whitmanian current in cultural criticism and prophecy of those years, to the writings of Rosenfeld, Van Wyck Brooks, Waldo Frank, Randolph Bourne, Lewis Mumford, William Carlos Williams, Constance Rourke, and Kenneth Burke. These writers took Whitman up on his bet that the words “America” and “democracy” might yet become synonymous and dared to hope that a modern culture they first glimpsed in the Port of New York—in steerage and in Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph of steerage–contained the resources for transcending the intellectual and political divisions of their country. Whitman’s gamble, as understood by these intellectuals, has been Alan’s as well. The practice of cultural criticism understood as cultural self-criticism might break the hold that ideological cliché and official myth exercise over the democratic imagination.

Alan’s knowledge of the critical roots of American Studies made it possible for him to see, early on, the points of contact between a Mumford or a Burke and the early work of Raymond Williams and E.P. Thompson—and beyond them, the whole sweep of Western Marxism. The romantic anti-capitalism at the heart of both Whitmanian criticism in the U.S. and the Western Marxist tradition of cultural critique was also a point of departure for the so-called “myth-and-symbol” school of early American Studies. It is too easy to say that Alan synthesized these three traditions in his work. As I consider his intellectual trajectory, it seems to me instead that Alan deployed each of these currents of cultural criticism to exert pressure on the other in order to generate a new approach to U.S. cultural studies. Mumford’s urbanism was reread and revised in light of Williams’s The Country and the City. Burke’s pragmatism leavened the economistic thrust of Marxism. Myth-and-symbol entered a fruitful exchange with hegemony theory. Alan’s Port of New York was not an entry point for exotic European theoretical goods; rather, it was an opening onto a horizon where radical cultural critics from different national and historical traditions might meet as intellectual equals and interlocutors. Once situated on that horizon, Brooklyn Bridge became The Incorporation of America. Another bridge, then, that Alan has given us as a cultural critic—a trans-Atlantic bridge, connecting New York to Britain and continental Europe.

Many of the hopes that animated the critical tradition to which Alan has so often returned no longer inspire much of what goes under the banner of American Studies today. Scholars in the field are more likely to emphasize the complicity of Whitmanian rhetoric in colonialist projects, and in the strategies of exclusion that narrowed the boundaries of citizenship, than they are to suggest its potential for a social-democratic future. In place of a bridge, much recent work in American Studies builds a wall between contemporary political commitments and a cultural history that stands accused not only of tolerating structures of domination but of constituting them. Personally, I note all this with regret but understand that many colleagues applaud this shift in sensibility as a momentous political and intellectual advance. Regardless of one’s feelings about the re-orientation of our field, there is no denying that the prospect of something called “America” serving as a vehicle for a radically expansive “democracy” seems even dimmer in the early twenty-first century than it did a hundred years ago.

I would argue nonetheless that one way of paying homage to Alan’s example is to pause and weigh carefully whether our understanding of the past and hopes for the future are richer for having walled ourselves off from the Whitmanian hope that has long impelled his “critical cultural history.” There is still need for the bridges Alan has built, in my opinion. Those bridges–as Alan wrote of the Roeblings’ great bridge forty years ago–“might still incite dreams of possibility, might yet become a symbol of what ought to be.”

0