One of the favourite serious recreations of educated people in Augustine’s day was the ‘philosophical weekend’. This was a little like a modern conference where a group of people with a specialist interest meet to listen to papers and discuss topics arising from them, except that it was not attended by specialists. It was a leisure pursuit anyone might follow, but with the serious purpose of making ordinary educated people see themselves as real practicing philosophers. For philosophy in the ancient world was not merely an intellectual exercise; it required of its adherents a way of life, the practice of self-discipline and moderation. From this world of debate survives the Saturnalia of [Augustine’s] contemporary Macrobius, in which a group of friends meet over the Roman holiday of the Saturnalia and ‘spend the greater part of their time for the whole holiday together’ in ‘discussions’ (disputationes) with lighter conversation on similar themes at mealtimes. There is a conscious comparison with Plato’s Symposium, another surviving classical ‘philosophical conversation’ taking the form of a ‘literary dinner’. We have already seen that Augustine himself set up such a meeting, though with a rather more open-ended timescale, soon after his conversion to Christianity, when he retired to Cassiciacaum on Lake Como with his mother and a group of friends to talk about the purpose of life and the ordering of the universe, topics as much philosophical as Christian. The senator Volusianus wrote to Augustine (Letter 135.2) about a similar ‘conversation weekend.’

–G.R. Evans, Introduction, City of God, translated by Henry Bettenson (London: Penguin Books, 2003), xxxiv-xxxv.

At present, we cannot gather together. We cannot meet face to face. We cannot travel. We cannot attend a conference, or a weekend retreat, or even a symposium. All of those things have rightly been canceled for the next few months because it is not safe to gather. Even if we felt safe, or unafraid, or indifferent to the risks of COVID-19 – and the more we learn about this disease, the less indifferent we should feel about how it might affect our own health – we must practice “social distancing” measures for the sake of those who are at greater risk than we believe ourselves to be. And even the young, the hale and hearty, the fit and strong, seem to be at enormous risk right now. So at present we must forgo our own version of symposia and “philosophical weekends.”

But we can read together at a distance, we can converse together from afar – and here is where we may do that and where we have been doing that for about thirteen years, ever since Tim Lacy launched this blog to connect to other grad students and scholars interested in U.S. Intellectual History. The connection from a distance preceded the fellowship of face-to-face meetings. The blog came first; the professional society emerged from the connections formed here. We are very fortunate to have this space already established, and we are fortunate to know that this model – thinking together asynchronously, enjoying a long philosophical weekend as we have the time to read and write and comment here – is a workable model for fostering meaningful connections with others, connections that sharpen our minds and warm our hearts.

If you follow me on Twitter, you know that, besides teaching five classes asynchronously, I’ve been spending home quarantine cooking everything from scratch and baking and gardening and building a compost bin and worm farming and distributing toilet paper via mail and giving bricks of yeast to local friends who need yeast for baking. (You know it’s the good sh*t when it’s packaged in bricks; this stuff is harder to come by than cocaine.) And – perhaps most amusingly to some of you, though certainly not a surprise to those who know me best – I have been immersed in experiencing and sharing the liturgical life of my church, recording the scripture readings in Spanish, inviting people to join the livestreamed liturgy of morning and evening prayer, live-tweeting the Sunday morning service with cues and text for various portions of the liturgy. I have a screengrab of the Nicene Creed and the Lord’s Prayer ready to go if you need it. And I have five copies of the Book of Common Prayer in Spanish — El Libro de Oración Común — if you need one.

And still there is time in the day, for which I am profoundly grateful. I have never been more grateful for time, nor more aware that the time I have in the day to call my own is entirely a function of my socioeconomic status, the kind of paid work I do, the kind of paid work my spouse does. We are all learning who is and who is not and essential employee when it comes to sustaining the basic functions of society. Non-essential employees can work from home; essential employees have to expose themselves to significant risk and go to work among the public in the middle of a pandemic. My spouse, unfortunately, is an essential employee, so our household is not as isolated right now as I would like it to be. But we are relatively secure compared to those who must constantly interact with others in order to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table. If we all do not come out of this cascading crisis with more equitable pay and benefits for those who are keeping the grocery shelves stocked and delivering orders and caring for those who need medical attention and keeping hospitals and stores and key work sites clean and sanitized, we will have learned nothing and squandered every bit of their time and our own.

And still there is time in the day, for which I am profoundly grateful. I have never been more grateful for time, nor more aware that the time I have in the day to call my own is entirely a function of my socioeconomic status, the kind of paid work I do, the kind of paid work my spouse does. We are all learning who is and who is not and essential employee when it comes to sustaining the basic functions of society. Non-essential employees can work from home; essential employees have to expose themselves to significant risk and go to work among the public in the middle of a pandemic. My spouse, unfortunately, is an essential employee, so our household is not as isolated right now as I would like it to be. But we are relatively secure compared to those who must constantly interact with others in order to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table. If we all do not come out of this cascading crisis with more equitable pay and benefits for those who are keeping the grocery shelves stocked and delivering orders and caring for those who need medical attention and keeping hospitals and stores and key work sites clean and sanitized, we will have learned nothing and squandered every bit of their time and our own.

Time is something that some of us have in abundance because our system extracts it from others’ lives in exchange for a pittance. This means that very few can simply retire to Cassiciacum and spend the days in contemplation.

But if you can do that in some small way – if, after all the extra work of teaching online (and it is EXTRA), and reaching out on the regular to your students, and rediscovering the joys of cooking every meal at home, and planting your plague garden, and sewing masks, and tending to whatever little flock God has placed in your care, you still find that you have the time to think – you should go ahead and do that without any sense of guilt. Because thoughtfulness and contemplation are essential employments. They are valuable not for what you can produce from them; they are worthwhile in their own right, and they are valuable for what they can produce in you.

You don’t have to be writing right now. You don’t have to emerge from the plague with the next Confessions or City of God – or even with the next peer-reviewed article. Or a first peer-reviewed article. Just say no – a resounding no – to the extractive demands that you be productive in the middle of a pandemic. Just come out of it. Just get through it. And if connection in conversation with others helps, please reach out. Leave a comment here, pose a question, let someone know you’re dying on the vine for want of some conversation or interaction or something to think about besides the craptastic crescendo of cataclysmic news. You’re not alone, even though you may be isolated and feel very lonely.

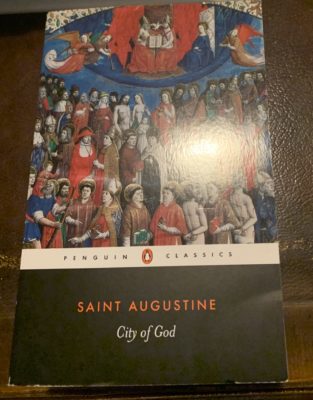

If you want to take a long philosophical weekend, you are welcome to join me and my friend Mark Thompson as we read through City of God together. It will take us all summer, and we’ll converse about it and write about it – probably here, maybe at my blog, who knows? – and you can read along with and chime in or just eavesdrop on the conversation. What does City of God have to do with American thought and culture? I don’t really know. Frankly, at this point, I don’t really care. It’s what we wanted to read, so it’s what we’re reading. Join us if you like.

Or if you have something you’d like to read in company with others, post about it in the comments here. Maybe someone would like to join you and converse about that text.

Just take care of yourselves. Take care of each other. And we will see each other again and converse face to face, as one speaks with dear friends.

14 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thank you very much for your wise and inspiring words. I have longed, throughout my life, for informed conversation. I am a conference junkie. For the last 35 years I have organized my entire life schedule around preparing papers for conferences, and then rewriting them for publication. Conference submission deadlines have provided my life backbone. It has been extremely satisfying. This year I had a number of speaking invitations and several papers accepted at conferences and of course all of this was wiped out by Corona. Since February I have been going through the stages of grief – and not getting too far along in them. But your reminder that we can create our own mini-conferences with our dearest colleagues, and share the intellectual life – and its corresponding life of friendship – while we are in isolation is heartwarming.

Well, you are welcome here Leonard. I’m so sorry for your grief — and it is right indeed to acknowledge it as grief — and for the loss of all you are missing. There are no silver linings; there are no “well, just think of it this way”s. It’s just an awful and disheartening time.

I miss the face-to-face work of teaching more than I can say — I am never happier than when we are rolling along through a discussion and hands are going up and questions are flying and I have to turn around and quickly write on the whiteboard in my awful scrawl and my students are laughing at my bad drawings and diagrams. That’s education and community and learning and growing together. Trying to replicate that in short videos and discussion boards and weekly video chat checkins is impossible. I am doing what I can for my students, but it’s a poor substitute and I grieve the loss of our class time together.

I’m glad you commented here, and I hope you’ll accept our open invitation to become a “regular.” And if you have a conference paper or idea you’d like to workshop, or if you want to put together a panel of your colleagues to discuss a topic, we would be very happy to publish it here and join in the discussion in the comments. Not a silver lining, but a way of helping each other through a rough time. You can send me an email at LBurnett AT Collin DOT edu.

Take care of yourself. I look forward to meeting you on the other side of this.

“What does City of God have to do with American thought and culture?”

Here’s one observation as I’ve finished Books I and II. Augustine helps me understand how people have consistently applied a dualistic understanding of causality and responsibility (How people narrow (maybe in a pragmatically useful way?) the possible factors involved in certain thoughts, words, or actions that—whether enacted or failed to enact—led to dramatic consequences (praise/blame for hindering/helping the deluge of COVID-19, e.g.). Is it natural or artificial? people seem to ponder? Should I stay or should I go? (sings The Clash). In the debate about why the virus spread, people are asking: Did this person not do enough or were they in the right? If the former, then another either/or neural path is opened up; the latter road again yields to more dichotomous thoughts (“If one cannot blame the person, one might aim their sights on an institution or ideology,” leading once again to the double-sided sensibility that is perpetually active).

His dualistic sensibility is not foreign to people in today’s politic climate. Despite the different ontological system Augustine used when referring to the two “citizens,” most people in the United States view things similarly through this bi-focal (or maybe dichotomous) sensibility. Instead of dividing people via Augustine’s theological manner into “goats” and “sheep,” people rely on political designations to locate “rational” or “irrational” voters; if one votes a certain way, they are seen as somehow Other, an enigmatic puzzle that defies logic or reason. I don’t think William James would have a difficult time understanding why people believe that one presidential candidate is more attractive than the other; these potential Presidents obviously are seen as tools for promoting certain effects.

Even the typical example of dualistic thinking, the mind-body problem, suggests that an almost Kantian faculty or category of the mind influences our decision; it is simply how the natural/objective world and our subjective construction of reality interacts. Even some scientists concur with this view. Psychologist Nicholas Humphrey, author of Soul Dust: The Magic of Consciousness (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), states:

“Thus, development psychologist Paul Bloom aptly describes human beings as ‘natural-born dualists.’ Anthropologist Alfred Gell writes: ‘It seems that ordinary human beings are “natural dualists,” inclined more or less from day one, to believe in some kind of “ghost in the machine”. . . .’ Neuropsychologist Paul Broks writes: ‘The separateness of body and mind is a primordial intuition. . . . Human beings are natural born soul makers, adept at extracting unobservable minds from the behavior of observable bodies, including their own.’”*

I admit I do a lot of head scratching when seeing the intensity of denunciations leveled at certain individuals who did not have the prophetic insight to anticipate the varieties of contingency daily shaping our mode of life (Not to denigrate the serious issues people are debating, but take just a minor example: Whether I get up on the right or left side of my bed: Will I strain my back if I choose one way rather than the other? Should I have known about the consequences and chosen accordingly?). Augustine’s text shows that people offered the same kinds of irrational responses that we encounter today. Why did the Empire fall? Not enough grain lad at the feet of Ceres? The common-sense assumption seems to be that whenever “badness” happens, blame is sure to rear its head as sure as winter follows autumn. The stoic approach to life (be willing to accept Fate and adjust one’s eyeglasses to ensure tranquility) does not seem to be a viable option for most people today. Is that attributable to our living as citizens in an “empire” as Augustine did, or would this anti-Stoic sensibility about blame and causation emerge if we were inhabitants of an isolated outpost? Was Thomas Haskell onto something about the interdependence of American society leading to confused notions of causal responsibility? Furthermore, is there something “American” about this usage for navigating daily life, or do other countries share this sensibility? I’m sure that Perry Miller and Ramus play a part here, but I don’t have time to revisit that dense jungle. . .

*Nicholas Humphrey, Soul Dust: The Magic of Consciousness (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 195.

Mark, you caught me being careless. City of God has *everything* to do w/ American thought and culture if we read it as a “timeless” text that can speak to our present moment. The whole problem / pretext behind the work — How did this once mighty city/center of civilization fall to ruin and whose fault is it? — is painfully germane.

I should have specified that I don’t know yet what it has to do with the history of American thought and culture. Where does City of God show up among the Founding Fathers, for example? Does Augustine have immediate interlocutors in the intellectual histories we have traced, or are we all his third-hand conversation partners as we get Augustine filtered through Luther and Calvin and from there to, I don’t know, Millerites and Mormons. America has its notions of original sin; how original are they?

But to your point — Augustine’s dualism is, by his own accounting, his Achilles heel. That’s the leftover detritus of the Manichaeism that he *thiought* he had left behind but that he could never quite escape. He fights dualism in DCD by a few strategies. In these first few books, his rhetorical recourse to pagan sources, which is apologetically useful, is also implicitly a rebuke to the dualism that would split “truth” and “error” (an eternal dualism [?], which claim would in itself be heretical) into neatly identifiable material dualisms of sources. Later, his insisting on the intermingling of the two cities and the impossibility of knowing to which someone belonged (not to mention the impossibility of anyone knowing to which city they themselves belonged) is another push against dualism.

I’m just not sure how hard Augustine is fighting dualism. Is he turning away from Manichaeism, or is he simply baptizing it?

“Augustine’s dualism is, by his own accounting, his Achilles heel. That’s the leftover detritus of the Manichaeism that he *thought* he had left behind but that he could never quite escape.”

This is the point also made by Ken Wilson (The Foundation of Augustinian-Calvinism): that Augustine returned to a Manichean determinism.

When I read Augustine’s indecision about knowing the actual inhabitants of the 2 cities, I still view this as a formal acknowledgement that nothing is problematic about dichotomous thinking (for him, maybe the sub specie aeternitatis?).

I guess I’m interested to know what this ancient primary source reveals about the distinctions conveniently made between the ancient, medieval, and modern worlds. At times, I find that the historical discontinuities are overstated; if Augustine (or, in my previous example, the people of Rome angry about their current plight due to the abandonment of the older gods) is showing the differences between our age and his (curse the demons!), is he also exhibiting continuities in ways of thinking (or sensibility)?

Not a bad question. I am sure the answer is yes — yes, he is exhibiting continuities in ways of thinking, BUT to what extent do we owe those common ways of thinking to the pervasive influence of Augustine himself (and those who trailed after him in time and thought) in shaping the sensibilities of the ages that followed his own? Am I overstating — or over-imagining — the case for Augustine? Perhaps. But you can count on one hand the thinkers/authors whose speculations and explorations and explanations marked and made the epochs of Christian thought over 1600 years — Paul, Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin. Do we have a Massachusetts Bay Colony without Calvin? No. And do we have Calvin — or Luther — without Augustine? No. (For that matter, we don’t have Augustine or even Paul without Plato, and we don’t have Aquinas without Aristotle).

It’s perhaps not possible to answer this question about what is influence and what is resonance. We have some sense of “the human condition,” perhaps another name for “human nature [with nature being constant — a nice Aristotelian idea!] as it suffers the vicissitudes of mortality.” And we could say Augustine speaks to the human condition and be quite correct. But it’s also true that Augustine helped invent and define the human condition — no wonder he resonates so!

tl;dr — heck if I know. But I am keeping on with the reading and am noticing some things. More later. In the meantime, I am hoping one of our interlocutors here, or a reader at home, will write another blog post on City of God and American thought/culture, broadly construed. This could be you!

I forgot to mention, of course, Arthur Lovejoy’s The Revolt Against Dualism. However, if I remember correctly, he charts this idea from Descartes onward. I wonder if there’s an Augustine to Descartes history out there about this specific topic (probably from a philosopher, I imagine).

Interesting discussion. Thanks for hosting it.

My contribution will hopefully be productive, although I’m afraid it might be somewhat beside the point of the main question: how does Augustine’s dualism – or his work the City of God – influence American culture? I’m not a historian, but a philosopher, so I am not qualified to answer this question. But I think I can shed a bit of light on the various “dualisms” Augustine contemplated over the course of his life.

First and foremost, it is fair to say that Augustine was a dualist of *some* kind for most of his adult life. The qualification here is intended to signal that he accepted different “dualisms” at different points in life. That is, the dualism he is committed to in his mature philosophical/religious works is different than the dualsim he accepted as a Manichean.

Manichean dualism denotes a dualism between two different types cosmic “forces” or “principles.” Yet, the dualism here is embedded and underwritten by a deeper commitment to materialism. This is evident by the Manichaean identification of the “good” force with “light” and the “bad” force with darkness. In The Confessions, Augustine recalls that one reason Manicheism originally attracted him was because he could not understand how something could exist and yet not be corporeal. But the primary appeal of Manicheism lie in how it solved a pressing philosophical problem: the problem of Evil: evil is the result of “forces” operating completely independently from the “forces” of light.

So Manichean dualism is not the metaphysically “deep” sort of dualism we find in Plato or Descartes. Rather, the difference between the two “forces” would be rather like the difference between two different physical substances. While their properties/dispositions are different, these two substances are at the end of the day of the same kind.

But when Augustine rejects Manicheism, he also rejects its underlying materialism. The “dualism” he embraces here is the familiar dualism of Plato etc: that of two categorically distinct modes of being, bodies (e.g. physical objects) and souls (e.g. God, angels, human souls). And of course, in opting for mind-body dualism, he inherits all of the problems associated with that tradition.

David,

Thanks for jumping in.

It seems like one could be an ontological monist and still harbor dualist tendencies. As I was saying above, the Familiar/Other form that people use (even today) to regulate their lives in a pragmatic way could be seen as an “Idea” (in the History of Ideas sense) or as a Kantian, a priori structure of the mind.

I guess I’m asking if Manichaeism appeared because it was suggested (implanted) through the ol’ Lockean senses or if it constitutes an inescapable part of the human condition. Have there been any post-Kantian philosophers that specifically dealt with this question?

Hi Mark,

It’s very nice to meet you. Thank you for your comment and the post you made above. I enjoyed reading it.

If you don’t mind, I will quote you and then respond. I do so only to keep things clear, not to play any sort of “gotcha” game.

You wrote: “It seems like one could be an ontological monist and still harbor dualist tendencies.”

I agree. I take it my original post suggested otherwise and that’s my bad. A person could absolutely be a monist about metaphysics and a dualist about other issues.

I think Augustine is a really good example of this tendency. Manicheism espoused a really simplistic view of morality insofar as it didn’t leave much room for shades of gray. I think the same black-white dynamic is at play for what you call “Familiar/Other” mode of categorizing people.

Then you write: “…I’m asking if Manichaeism appeared because it was suggested (implanted) through the ol’ Lockean senses or if it constitutes an inescapable part of the human condition. Have there been any post-Kantian philosophers that specifically dealt with this question?”

I maybe not understanding your question here. I will try to reformulate it, but please let me know if I didn’t do so correctly.

I take it you are asking whether Manichean-type thinking – by which I mean, black-white/ridgid ways of framing experience – is something that is learned or something that is innate in humans. My answer is neither. I think these sorts of frameworks arise from a complicated mix of genes and culture and I don’t think we yet know how to tease these two things apart (or whether even if it is possible to tease biology and culture apart).

II think it’s because I’m using the term “dualism” in multiple ways (maybe too loose)—as an idea, structure of the mind, or sensibility—that my comment might have caused confusion. I don’t necessarily think of dualism (or dichotomous thought/form) as inherently simplistic. In Augustine’s case, if he sees the world as inhabited by people on the path to either 1 of 2 cities (God or Man), the path to those roads is anything but simplistic in his overall theology. As L.D. mentioned above, Augustine admitted that knowledge of who was going where was not definitively revealed to his fallible, human self. If I’m playing tennis, I can hit the ball to the right or left of my body (because my physical, symmetrical shape limits my options), but there are all kinds of additional factors to consider (amount of topspin, force, location, ad nauseum).

The question about whether people can avoid seeing in “twos” for particular modes of thinking or reasoning appears to have been taken over by psychologists, neuro-biologists, and others from that disciplinary background. It seems like Kant was the last to attempt a totalizing worldview that involved, nature, consciousness, and metaphysical ideas (such as “free will”).

I’m curious if any philosopher after Kant—Merleau-Ponty, possibly—has tried to explain the prevalence of dualistic thinking by looking at it either as an idea (in which case, again, I was thinking of the [sometimes hackneyed and misleading] dispute between Rationalists and Empiricists), or an innate, way of interacting in this 4-dimensional space-time continuum?

Re Mark T.’s comments above: It could be (I don’t know) that there is a predisposition to think in “twos”.

On the other hand, certain people (Hegel, e.g.?), in certain contexts at any rate, seem to have been attracted to thinking in “threes”.

Here’s one specific example. The late Stanley Hoffmann, who was born in Vienna and grew up in France before becoming an academic in the U.S., made the passing observation in an autobiographical essay that “I think I have become quaintly legendary for making all of [my arguments] in three parts….” (S. Hoffmann, “To Be or Not to Be French,” in _Ideas and Ideals_, ed. L. Miller and M.J. Smith, Westview Press, 1993, p. 41)

Yes, Louis, threes, sevens, and tens have their followers as well (I think Peirce had a fixation on 3, if I remember). Hopefully something will come of this (admittedly, too general) speculative take on the significance of Augustine for thought and culture in the United States.

Two might also be promoted simply for the felicity of expression (Laurel and Hardy; Ben and Jerry; Salt and Pepper—and let’s not forget the singing duo Salt-N-Pepa); it’s easier to reach for the salt and pepper than salt and pepper and thyme, I guess?

Lora & Friends,

I won’t be reading City of God with you, but I appreciate the effort and spirit behind the call.

As a permanent great bookie—hooked on that category long before I studied it—I appreciate all efforts to engage texts with pretensions to timelessness. As a historian I know that not text nor author ever fully escapes their times, but I think some try harder to engage ideas that transcend. For my part, I’ll follow your discussion, even if I don’t post on it. I might drop a comment here and there—because I consider Augustine an old friend. 🙂

Otherwise, I’m with you 100 percent on letting one’s “productivity” be happenstance, or redefining it in ways that feel useful in the moment. I don’t want to have been a slave to productivity such that if/when I catch the COVID-19 virus (knock on wood), that I have REGRETS.

Side note: I appreciate the civility and politeness of the thread above. Reminds of some of the good old days around this space (an arena, as Lora notes, has been part of my life for 13 years).

Peace, TL