The Book

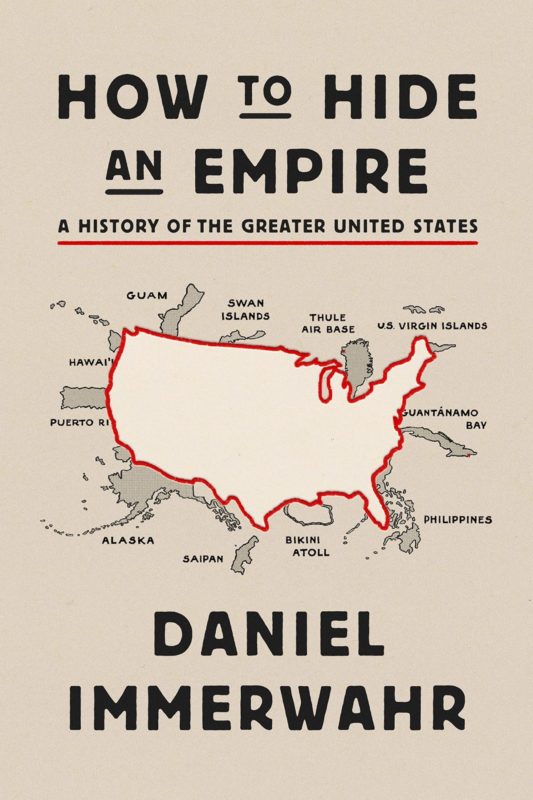

How to Hide An Empire: A History of the Greater United States

The Author(s)

Daniel Immerwahr

Editor's Note

Last week, the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians ran a review essay, link here, by Anne Macpherson on Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire. Dr. Immerwahr has written a response to that essay.

Anne Macpherson has written a thoughtful reflection on my book, and I’m grateful for the chance to reply. Macpherson is a Caribbeanist and from that perspective has four major objections. First, she argues, I don’t fully explain how the U.S. territories were hidden from mainland view. Second, I downplay the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories. Third, I fail to appreciate the Greater Caribbean as the setting for Puerto Rican history. Fourth, I leave out other important aspects of Puerto Rico’s past. I’ll reply briefly to these objections, handling a few smaller matters in footnotes.

The title of my book is How to Hide an Empire and throughout I give examples of mainlanders ignorant of the fact that the United States has a territorial empire. The problem continues today. Yet Macpherson doesn’t think I explain this ignorance satisfactorily. For her, what is “hidden” by my book is that “the federal government does not want Americans to notice the non-incorporated territories or what their existence means about the character of the United States.”

I agree with Macpherson that the federal government has played a role, and I don’t believe I hide that fact. Indeed, I show how the census, presidents, and Supreme Court have helped relegate the overseas territories to the margins.[1] But I think we need a broader explanation. Alongside and informing the governmental marginalization of the colonies, there has been a strong current of popular racism leading mainlanders to dismiss the overseas territories as foreign and irrelevant. In my book, I discuss how Broadway musicals, non-governmental maps, and mainland journalism have consistently written the colonies out of the story, too. The combined effect has been to make the United States seem like a nation-state rather than an empire, a contiguous country with no territories.

Macpherson bristles at my talk of “territories.” She notes that Puerto Rico, the focus of her research, is not just a territory but a particular type of territory: an unincorporated territory. In the early twentieth century, the Insular Cases divided the United States’ annexed lands into two categories. Of the overseas territories, the Supreme Court ruled that the ones with larger white settler populations, Hawai‘i and Alaska, were incorporated, while it ruled that the others were unincorporated. Macpherson fears I don’t stress the distinction enough. She writes that my book spends only a “miniscule” amount of time on the topic (4–5 pages, actually) and that I often speak generally of “territories” without distinguishing the legal flavors.[2] “Non-incorporation is simply not an organizing principle” of How to Hide an Empire, Macpherson writes.

She’s correct, it’s not. But should it be? I’ve been influenced by the work of legal historian Christina Duffy Ponsa-Kraus, a specialist on Puerto Rico and a central scholar on this topic. Ponsa-Kraus argues that “the significance of the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories has been substantially exaggerated” and points out that the incorporated territories were also legally subordinated to the states.[3] In my own research, I saw incorporated territories treated as colonies just as unincorporated ones were. Hence, for example, the imposition of brutal martial law on the Territory of Hawai‘i from 1941 to 1944, justified by the federal government because Hawai‘i was a territory and not a state.[4] Hawai‘i was incorporated, but that did little to protect it.[5] I’m extremely uncomfortable with Macpherson’s persistent identification of colonialism with non-incorporation, as if Hawai‘i, Alaska, and Indian Territory weren’t also colonized.

She’s correct, it’s not. But should it be? I’ve been influenced by the work of legal historian Christina Duffy Ponsa-Kraus, a specialist on Puerto Rico and a central scholar on this topic. Ponsa-Kraus argues that “the significance of the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories has been substantially exaggerated” and points out that the incorporated territories were also legally subordinated to the states.[3] In my own research, I saw incorporated territories treated as colonies just as unincorporated ones were. Hence, for example, the imposition of brutal martial law on the Territory of Hawai‘i from 1941 to 1944, justified by the federal government because Hawai‘i was a territory and not a state.[4] Hawai‘i was incorporated, but that did little to protect it.[5] I’m extremely uncomfortable with Macpherson’s persistent identification of colonialism with non-incorporation, as if Hawai‘i, Alaska, and Indian Territory weren’t also colonized.

There are two other good reasons to consider non-state spaces under U.S. jurisdiction together, rather than starkly dividing incorporated from unincorporated territories. First, doing so allows us to connect settler colonialism and overseas empire by making room for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century territories—these were neither incorporated nor unincorporated because the legal distinction didn’t yet exist.[6] Second, it makes it easier to recognize continuities between inhabited overseas territories and other overseas administered spaces, such as uninhabited islands, military bases, and occupation zones, which I believe should also be part of the story, even if they don’t fit into the incorporated/unincorporated schema.[7]

Macpherson’s next objection concerns geography. She stresses the importance of the Greater Caribbean—“a blurry-edged ecological, economic, social, and cultural region”—for Puerto Rican history. She gives examples of scholarship that profitably places Puerto Rican history within that context. But How to Hide an Empire is “conceptually at odds with Greater Caribbean historiography,” she writes, because it groups Puerto Rico with Hawai‘i and Guam rather than with Jamaica and Colombia.

It does, but I don’t agree that there is a conceptual clash here. The Greater Caribbean is one useful frame; the Greater United States is, I hope, another. None of the scholars contributing to the Greater Caribbean literature have to my knowledge insisted that their geographic focus is the only way to contextualize Puerto Rican history, and I certainly don’t make any such claim on behalf of the Greater United States. In fact, some of the books she cites as central to our understanding of the Greater Caribbean—by José Amador, Michael Donoghue, and Jorge Duany—were also crucial in informing my narrative.[8]

Historians encounter different geographical frames all the time. We can understand Texas as part of the U.S./Mexico borderlands, part of a global oil empire, and part of the former Confederacy. None of these geographies contradicts the others, and all are relevant to making sense of Texas. Similarly, in suggesting that we can productively understand Puerto Rico as part of the U.S. territorial empire, I am not hiding, rejecting, denying, or diminishing Greater Caribbean historiography. I’m just doing something different.

But Macpherson thinks there are other important aspects of Puerto Rican historiography that I “hide,” beyond the Caribbean turn. My book “ignores” Puerto Rican history before 1898, offers only glimpses of it past the 1950s, and tells the reader too little about Puerto Rican women and gender, party politics, racial identities, capitalism, labor conditions and organizing, and the diaspora. Again, Macpherson cites a rich literature.

And again, I fail to see the problem. How to Hide an Empire tries to engage readers in the history of the U.S. territorial empire through what Macpherson rightly calls an “episodic narrative.” Puerto Rico receives more attention than most places, accounting for three of the book’s twenty-two short chapters. But this is not a book that makes the slightest gesture toward offering comprehensive coverage of any territory or overseas space. Similar gaps could easily be found in my treatment of Hawai‘i, the Panama Canal Zone, Guantánamo Bay, Dhahran, or the Northern Marianas.

The stronger claim would be to point out not what How to Hide an Empire omits but what it thereby gets wrong. Here Macpherson is less forthcoming. The themes I do treat, she allows, are “important.” The main interpretive sin of which she accuses me is this: by saying little about Puerto Rico after the 1950s, I make it seem as if Puerto Rico was no longer a colony. Perhaps this was a cost of my moving onto other topics, yet nowhere do I claim that Puerto Rico’s colonial status ended. Just the opposite, in fact. In 1952, I tell how the territory got a new constitution and became a commonwealth.[9] But, as I write, “the actual lines of authority didn’t change” and I note that the lawyer who drafted the constitution “maintained that Puerto Rico was still a colony.”[10] Whether it is remains a subject of heated political debate today. Macpherson counts Puerto Rico as a colony still, though, and so do I. In my book’s conclusion (“Enduring Empire”), I argue that “empire lives on” in Puerto Rico and the United States’ four other inhabited territories.[11]

Macpherson feels that I don’t say enough about the parts of Puerto Rican history she finds essential. But could any broad narrative about the U.S. territorial empire satisfy Macpherson’s demands for comprehensiveness vis-à-vis Puerto Rico? I am not sure. The sole example Macpherson gives of an acceptable book that covers the U.S. empire beyond Puerto Rico is Alfred McCoy and Francisco Scarano’s Colonial Crucible, a 685-page, co-edited anthology to which 48 authors contributed. I share Macpherson’s admiration for Colonial Crucible, yet even that terrific work has tremendous gaps and makes no attempt to cover many of the areas of Puerto Rico under U.S. rule that Macpherson faults me for saying too little about: gender, post-1952 cultural nationalism, labor organizing, migration/diaspora. Still, Macpherson concludes that Colonial Crucible achieves something that “no single-authored volume can do with regard to the non-incorporated territories” because “their historiographies are simply too large for any one person to master and synthesize.”

If Macpherson is correct that no one could ever command the expertise to write a history of the U.S. territorial empire, then that’s bad news for our field. But I’m more optimistic. I’ve read Julian Go’s Patterns of Empire, which synthesizes not only research on U.S. colonies but research on the British Empire, too, into a sharp, thoughtful account.[12] I’ve read Lanny Thompson’s Imperial Archipelago, which carefully considers the continuities and differences in imperial governance in the United States’ various colonies.[13] And I’ve read recent articles by Alvita Akiboh and Funie Hsu, which respectively tell the tales of U.S. money and English-language instruction within the empire.[14] Such works don’t profess to capture every historical detail or historiographical tendency. But they are informed, authoritative, and illuminating.

Macpherson concludes with the hope that we will be able to “steer students of U.S. history toward the library shelves” where the books on U.S. colonies reside. That is my hope, too. I am grateful to her for writing a review that highlights what a rich trove of scholarship sits upon those shelves.

[1] Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), census: 12–13, 78–79; presidents: see especially 4–7 and 111–112; Supreme Court, 83–87.

[2] Ibid., 83–87, plus later references to the Insular Cases at 104, 257, and 394–395.

[3] Christina Duffy Burnett, “Untied States: American Expansion and Territorial Deannexation,” University of Chicago Law Review 72 (2005): 801. The author now goes by Christina Duffy Ponsa-Kraus.

[4] Immerwahr, How to Hide, 177. The most extensive coverage of this episode is Harry N. Scheiber and Jane L. Scheiber, Bayonets in Paradise: Martial Law in Hawai‘i during World War II (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2016).

[5] Macpherson says that Hawai‘i and Alaska were “always incorporated territories on a path to statehood.” This statement is false in two ways. First, Hawai‘i and Alaska were annexed before the Supreme Court ruled them incorporated—decades before in Alaska’s case. Second, it was far from clear in the early twentieth century that either would become a state. Both territories had majority nonwhite populations, and there was strong racist resistance to admitting either to the union. See, for example, Eric Love, “White is the Color of Empire: The Annexation of Hawaii in 1898,” in Race, Nation, and Empire in American History, ed. James T. Campbell, Matthew Pratt Guterl, and Robert G. Lee (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 75–102.

[6] The importance of placing settler colonialism and overseas empire together analytically is emphasized in Alyosha Goldstein, ed., Formations of United States Colonialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014) and a helpful recent example is Katharine Bjork, Prairie Imperialists: The Indian Country Origins of American Empire (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

[7] Key works on bases particularly are Catherine Lutz, ed., The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against U.S. Military Posts (New York: New York University Press, 2009) and David Vine, Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Abroad Harm America and the World (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2015). A terrific reflection on the other point-like spaces within the U.S. territorial empire is Ruth Oldenziel, “Islands: The United States as a Networked Empire,” in Gabrielle Hecht, ed., Entangled Geographies: Empire and Technopolitics in the Global Cold War (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011), 13–42.

[8] José Amador, Medicine and Nation Building in the Americas, 1890–1940 (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2015); Michael E. Donoghue, Borderland on the Isthmus: Race, Culture, and the Struggle for the Canal Zone (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014); Jorge Duany, The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

[9] Macpherson takes me to task for a radio interview in which I said that Puerto Rico had a “constitutional change” in 1952 and became a commonwealth. “There was no constitutional change,” she insists, as if correcting a factual error. This strikes me as a bad-faith reading. Puerto Rico got a new constitution in 1952, which is what I was talking about. Macpherson, ignoring the most plausible interpretation of my words, objects because in her view 1952 did not alter Puerto Rico’s standing under the U.S. Constitution.

[10] Immerwahr, How to Hide, 257, 258.

[11] Ibid., 400. Macpherson has two smaller, cross-cutting interpretive concerns: first she objects that I focus on nationalism and violence at the expense of “party politics” and then, two paragraphs later, she protests that I “hide” the harsh incarceration of nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos in the post-1952 period, thus concealing the brutality that undergirded the smooth operation of party politics. Actually, I devote two paragraphs to Albizu’s incarceration (p. 259), and do so in the context of a larger discussion of Puerto Rican party politics beyond violent nationalism.

[12] Julian Go, Patterns of Empire: The British and American Empires, 1688 to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[13] Lanny Thompson, Imperial Archipelago: Representation and Rule in the Insular Territories under U.S. Dominion after 1898 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2010).

[14] Alvita Akiboh, “Pocket-Sized Imperialism: U.S. Designs on Colonial Currency,” Diplomatic History 41 (2017): 874–902; Funie Hsu, “The Coloniality of Neoliberal English: The Enduring Structures of American Colonial English Instruction in the Philippines and Puerto Rico,” L2 Journal 7 (2015): 123–145.

About the Reviewer

Daniel Immerwahr teaches U.S. history and global history at Northwestern University. His first book, Thinking Small, won the Merle Curti Prize in Intellectual History and the Society for U.S. Intellectual History’s annual book prize. His second, How to Hide an Empire, was a national bestseller and the finalist for the Mark Lynton History Prize. Immerwahr’s writings have appeared in the New York Times, The Guardian, The New Republic, The Nation, and Slate, among other places.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

A couple of notes on a tangent, so to speak.

Re the connection, in the U.S. context, between settler colonialism and overseas empire, and as note 6 puts it, the “importance of placing settler colonialism and overseas empire together analytically”: the emphasis on this connection and on pre-1898 U.S. imperialism (or empire-building) is not solely a product of recent historiography, though I’m sure recent historiography has thrown new light on it.

Even if W.A. Williams and his students/disciples always emphasized the connection (and I frankly am unsure whether they did or not — maybe not?), the point isn’t/wasn’t limited to them. Just to take one example, Geoffrey Barraclough, in An Introduction to Contemporary History (1964, pb 1967), wrote that U.S. imperialism did not occur “suddenly and without precedent in 1898” and that American policy “[f]rom the beginning…looked out across the Pacific to Asia….” (p. 101) More recently, and without (as I recall) using the phrase “settler colonialism,” political scientist John Mearsheimer stresses the 19th-cent U.S.’s “aggressive behavior in the Western Hemisphere,” expansionism, and its establishment of “regional hegemony” over the course of the 19th cent. (Quotes from Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, p. 238. He’s wrong about a lot in this book, but not about that.)

Another possibly interesting angle is a comparative one. The official U.S. myth — which one can hope Prof. Immerwahr’s book might help to undermine — is that the U.S. has never been an imperialist power, unlike the “old” European great powers, esp. say Britain and France. Today, though, the actual configuration of the U.S. and French territorial empires arguably looks not too different: the French have a few overseas possessions of one status or another, remnants of what was once an extensive territorial empire, and the U.S. has some overseas possessions, remnants of what was once a somewhat less extensive territorial empire than the French one. The difference, or a difference, is that France does not pretend its overseas possessions don’t exist, whereas the official U.S. stance, as presumably reflected in public school curricula for example, is basically to ignore Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Marianas etc. and pretend they aren’t there, and also to downplay the global network of U.S. military bases.

Both of these points seem important to me. In my book, I argue that the United States was distinctive among large empires in having a metropole that was by and large unaware of the colonies. A helpful point of comparison is the UK. The British had a holiday, which started in the schools and gained official recognition in 1916, called “Empire Day.” Children dressed up in national costume of various colonies and gazed at the map of the empire on the classroom wall. The USA had its own patriotic holiday with an identical chronology: it started in the schools and became official in 1916. But it was “Flag Day,” it was explicitly designed to celebrate the nation rather than the empire, and the object of reverence was not the imperial map but the U.S. flag, which had a star for every state but no representation at all for the territories.

I don’t think that Daniel Immerwahr’s response to my review really engages with my core points. I argue that he treats the “logo map” as explanatory rather than symptomatic. I argue that he homogenizes incorporated and unincorporated territories. Of course the former were also subordinated to the states, but not in the same ways and not permanently. Nowhere in the book did I find an explicit justification for grouping all territories together or a robust discussion of what the various methods of subordination were. Non-incorporation is a distinct and ongoing set of imperial practices. Incorporated territories were always on a path to statehood and have all become states. Puerto Rican statehooders sometimes pretend that because of this it should be straightforward for Puerto Rico to follow suit; it is non-incorporation that disproves their argument. I am not arguing that the Greater Caribbean frame is the only way to frame Puerto Rican history, I am arguing a) that it is a very important frame that the book ignores and b) the Greater United States frame–even if used alongside others–is not good precisely because it wants to make the non-incorporated territories “part of” the United States. The “Greater United States” concept is at the basis and core of the book, and it is deeply flawed and in my view irredeemable. Finally, I am not simply arguing that the book’s account of Puerto Rico is incomplete, I am arguing that its conception of Puerto Rican history and historiography is flawed and distorted. It is not a framework that can be added onto; it needs to be rebuilt, starting with recognition of pre-1898 history, of post-1873 Puerto Rico as a post-emancipation society, and forcefully of post-1952 history. Yes, the book invokes Albizu’s last years on page 259. But this brief mention is contained in a chapter about the 1950s, and the fact that Albizu lived to the mid-1960s–well into the period when the US was supposedly massively decolonizing-is not mentioned. I applaud Daniel’s passion to make US historians and the American public aware of the history of “the territories”; I just think that the way How to Hide an Empire tries to raise awareness is flawed at the root.

Anne, it sounds as if you are arguing that any account of Puerto Rico, even an episodic one, that does not delve into its pre-1898 history, that does not present it explicitly as a post-emancipation society, and that does not explore its post-1952 history at length, is not only incomplete but “flawed and distorted.” We may have reached an impasse. I’ll just note that your Journal of American History article on the colonial minimum wage, which I like very much, does none of those things.

That article, you write, seeks to place formal empire “at the heart of metropolitan historiography.” That is precisely what I think the Greater United States concept does. So, yes, I’ll plead guilty to wanting to make unincorporated territories “part of” U.S. history. I think that’s exactly what you’re doing in that article, too, and doing artfully (in fact, you published it in a U.S. history journal). Puerto Rico has many historical trajectories: as part of the former Spanish Empire, as part of the Caribbean, as a post-emancipation society. One of them is that it has also been part of the United States. To write about that reality is not to endorse it or to argue for statehood. It’s to grapple with the fact that the United States has been and remains an empire.

We may well be at an impasse! About my JAH article. First, it’s just an article, with a limited word count, on 1938-41. Elsewhere, for example in my Small Axe essay, I have traced Puerto Rican history across the watersheds of 1873 and 1898 while comparing it to Belize in that same long period. Second, even as it tries to get US historians to pay attention to Puerto Rico as relevant to their enterprise, it argues that Puerto Rican history and historiography cannot and must not be subsumed within US history and historiography. I reiterated this point in a key paragraph of my critical review of HTH – that US historians have to hold in tension Puerto Rico as something simultaneously relevant to US history and something separate from US history. The “Greater United States” concept and framing simply don’t allow for this to happen, which is why I urge US historians not to adopt them. Finally, this is what I found in HTH about pre-1898 Puerto Rican history: “For centuries Puerto Rico had endured colonial rule with little direct resistance” (146). There are two problems with this. First, it comes awfully close to reproducing a trope of Puerto Rican docility (often in contrast to Cuban ferocity) that generations of scholars have worked to disprove. Second, it means that HTH conjures Puerto Rico into existence at the moment of US invasion – that’s when and why it becomes relevant. Even just the history of US-Puerto Rico connections and relations pre-dates 1898, and shaped responses to the US invasion.

Our disagreement is whether to see these historiographical frames as exclusive. I don’t. Your own work is an example: in your JAH article you operate within a Greater United States frame (hooray!) but in your other writing you invoke other useful frames (also hooray!).

My line about Puerto Rico’s longtime relative lack of “direct resistance” is from a discussion of violent nationalism. Pre-1930s Puerto Rico saw markedly less of that than Cuba or the Philippines, both of which were devastated by repeated wars for independence. But if you’re worried that my book reproduces a “trope of Puerto Rican docility,” I have good news: that statement is immediately followed by an account of nationalist uprisings on the island. In fact, in your initial essay, you object that I focus on Puerto Rican anticolonial violence too much.