Editor's Note

The following is part three of a longer series about phenomenology, and specifically Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s book, The Phenomenology of Perception. Last time out I described what Maurice Merleau-Ponty meant by “phenomenology” and considered how phantom limb syndrome might help us work out that meaning. But this approach can also suggest an interesting way to do history with its concerns in mind, specifically with respect to how Merleau-Ponty understood the body and space. Today I’ll describe a historical incident of phantom limb syndrome to set up a phenomenological approach to history. In posts to follow, I’ll return to Merleau-Ponty and offer a few suggestions for how to read the case.

Many of our number have read or even assign George Santayana’s luminously written essay in intellectual history, “The Genteel Tradition in American Philosophy” (1911). It was partly an act of mourning for William James, who had died the previous year. No doubt Santayana bears some of the blame for the widespread tendency of historians in the decades that followed to treat James’ thinking as somehow the most sophisticated expression of the American “mind” or “character.” In a larger section about how James’ tolerance and curiosity–his excess of democratic sentiment–helped Americans cope with the modern world, these lines have always struck me:

For one thing, William James kept his mind and heart wide open to all that might seem, to polite minds, odd, personal, or visionary in religion and philosophy. He gave a sincerely respectful hearing to sentimentalists, mystics, spiritualists, wizards, cranks, quacks, and impostors — for it is hard to draw the line, and James was not willing to draw it prematurely. He thought, with his usual modesty, that any of these might have something to teach him. The lame, the halt, the blind, and those speaking with tongues could come to him with the certainty of finding sympathy; and if they were not healed, at least they were comforted, that a famous professor should take them so seriously; and they began to feel that after all to have only one leg, or one hand, or one eye, or to have three, might be in itself no less beauteous than to have just two, like the stolid majority. Thus William James became the friend and helper of those groping, nervous, half-educated, spiritually disinherited, passionately hungry individuals of which America is full. He became, at the same time, their spokesman and representative before the learned world; and he made it a chief part of his vocation to recast what the learned world has to offer, so that as far as possible it might serve the needs and interests of these people.[1]

For my purposes, the line, “they began to feel that after all to have only one leg, or one hand, or one eye, or to have three, might be in itself no less beauteous than to have just two, like the stolid majority” is more than a little thought provoking, not the least because it calls attention to American bodies.

George Santayana also knew that William James’ father, Henry Sr., had lost a leg as a young man. In what should be considered another act of grieving, some five years following his father’s death, William published an article for The Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research

called “On the Consciousness of Lost Limbs” (1887).

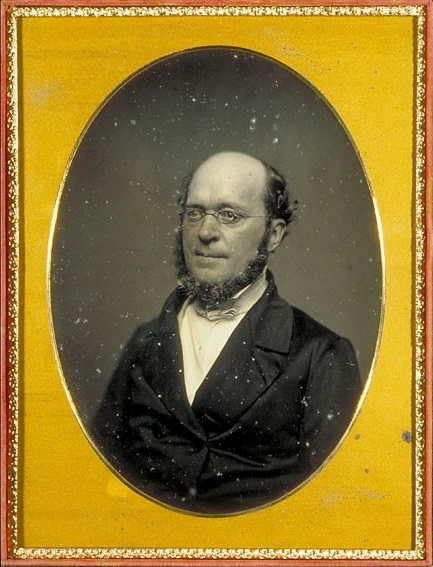

Henry James, Sr.

In that article, James admitted frustration with the phenomenon. The essay was one of those offshoots from work that would become The Principles of Psychology. Around the same time, the philosopher had published a four part series of articles for the journal Mind on the “The Perception of Space.” (I’ll return to those articles in my next post.) For “On the Consciousness of Lost Limbs,” James gathered subjects in an effort to find some commonalities in the experience, conducting a survey of nearly two hundred amputees from lists he got from prosthetic limb manufacturers. He couldn’t account for a physiological cause. He noted wild differences in the experience, from where people felt their losts limbs, to how they felt them, to the amount of time they felt them (in some instances the syndrome disappeared after a time). As for that last variable—the amount of time experienced—he offered the following example:

The oldest case I have is that of a man who had had a thigh amputation performed at the age of thirteen years, and who, after he was seventy, affirmed his feeling of the lost foot to be still every whit as distinct as his feeling of the foot which remained.[2]

This was clearly William James’ father. It would be hard to imagine it being anyone else, unless James knew more than one septuagenarian who happened to have lost his leg at age thirteen. In a footnote to selections from his father’s Literary Remains (1884), William James mentioned of his father’s leg that “At the age of thirteen, Mr. James had his right leg so severely burned while playing the then not unusual game of fire-ball that he was confined to his bed for two years, and two thigh amputations had to be performed.”[3]

The story of how Henry Sr. lost his leg goes like this: As part of scientific instruction in their Albany, New York academy, young Henry and his schoolmates sometimes experimented with paper air balloons, open at the bottom, heated from underneath with an attached ball of tow soaked in turpentine and set on fire. The ball of tow sometimes ignited the balloon, and, burning through its attachments, the lit ball would then fall to the ground, where the boys would kick it around. Attempting to stamp out a fire from an errant fireball that threatened a hayloft, Henry was badly burned. A period of horrible morbidity followed. The young Henry’s confinement lasted even longer than William remembered. The first amputation was probably botched, leading to a second some years later. We can gather that Henry suffered tremendously, seeing how anesthesia wasn’t in widespread use at the time.[4] I think it had a largely under-appreciated influence on William James and his being-in-the-world.

Next time out, I’ll treat some philosophical details from William James to connect things, moving back into The Phenomenology of Perception to begin filling out the story. To preview, Merleau-Ponty did something beautiful in the book. He showed how people we might think damaged or strange have worlds too. As George Santayana knew, William James did the same thing in his own work. James’ attempt to normalize phantom limb syndrome in “On the Consciousness of Lost Limbs” is stunning. What if, as I mentioned last time out, Merleau-Ponty is right, and phantom limb syndrome is a mode of grieving, a kind of denial? If so, then James’ account is like phantom limb syndrome, in this case the ambivalent presence of his father. This case can be made in ways other than straightforward psychoanalytic ones, and with a surprising degree of philosophical rigor. That William James worked on the cusp of phenomenology only complicates the story even more.

[1] George Santayana “The Genteel Tradition in American Philosophy (1911),” online at http://monadnock.net/santayana/genteel.html

[2] William James, “On the Consciousness of Lost Limbs,” Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research 1, 249-258. Online at https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/lostlimbs.htm

[3] William James in William James, ed. The Literary Remains of Henry James (New York, Houghton-Mifflin, 1884), 174.

[4] Alfred Habegger, The Father: A Life of Henry James, Senior (Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, ), 66-82. See also Henry James (the son of William James), in Letters of William James, vol. I (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1920), 7-8. The most thorough account of the fireball episode is Howard Feinstein, Becoming William James (Cornell, 1984), 68-75.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Brilliant. History is a phantom limb. Can’t wait to see how you stick the landing.