About the only words I can manage to produce these days are the lectures I produce ex tempore in the classroom. Sometimes, when the discussion has been lively, I take pictures of the whiteboard at the end of class. Always, what appears on the whiteboard is shaped by the questions and comments of my students as we go along.

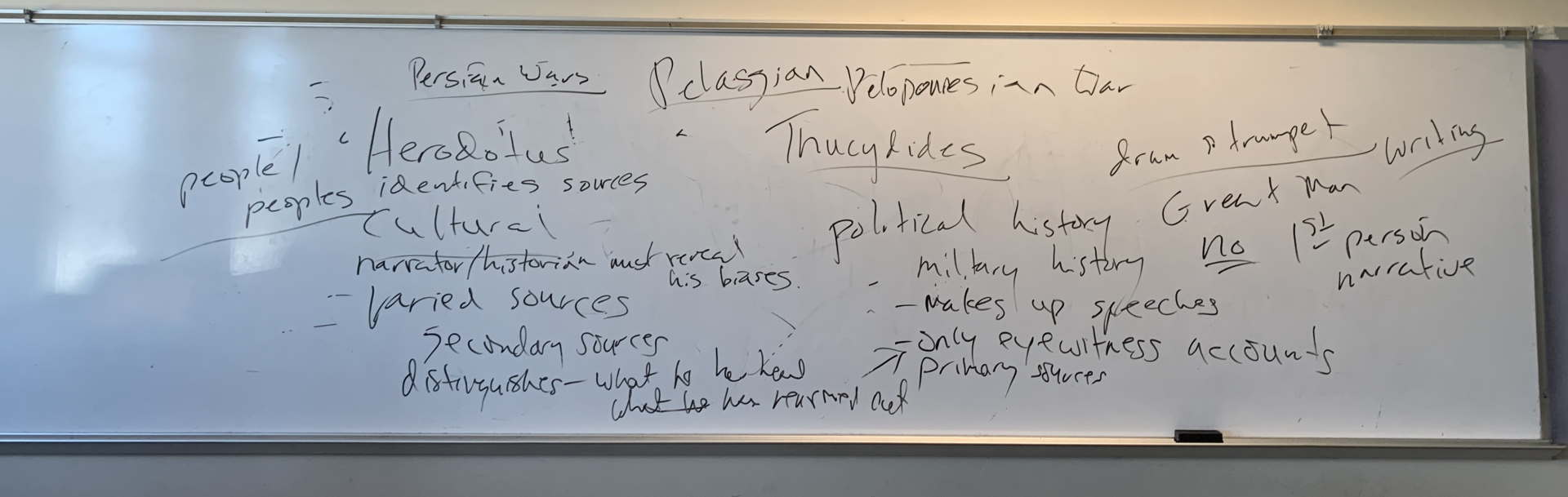

Here’s the final whiteboard from my Western Civ class the week before last, when we discussed Herodotus.* They had read about both Herodotus and Thucydides in the textbook, but I only assigned them selections from books I and II of Herodotus for the primary source readings. As you can see, we discussed what distinguished the two historians’ approaches from one another (though I should note that “primary sources” was something I also mentioned for Herodotus, while emphasizing how much he relied on – and acknowledged – secondary informants).

Herodotus and Thucydides, Feb. 6, 2020

I pointed out to them the extent to which historical writing today tries to navigate between Herodotus and Thucydides, including our own Western Civ textbook – sweeping panoramas of cultural norms and cultural change and the telling details of daily life on the one hand, and on the other hand the sustained focus on wars and founders, empires and borders, dudes and dates. The first half of each chapter is generally more Thucydidean, while the second half usually ranges into Herodotean registers – first the political history, then the cultural history. And in our own writing historians struggle with the models and strictures laid down by Herodotus and Thucydides – what is the purpose of writing history, and what is the place of the historian in relation to the sources they use and the account they produce? It was a good discussion.

From last week’s class, I sorely wish I had taken a snapshot of my illustration of Plato’s allegory of the cave. I’d never taught Plato before, so had never had occasion to draw out the allegory before, but I did it on the fly and it turned out great. I told my students this is probably the most famous mental picture in all of Western philosophy; the trolley problem is possibly a close second. “If you know how to talk about the allegory of the cave,” I said, “you can b.s. your way through a cocktail party.”

No, that’s not the reason – the good, as Aristotle might say – for which I am teaching my Western Civ students about Plato and Aristotle. But it’s a beneficial side effect for them – an accident of education, not its essence.

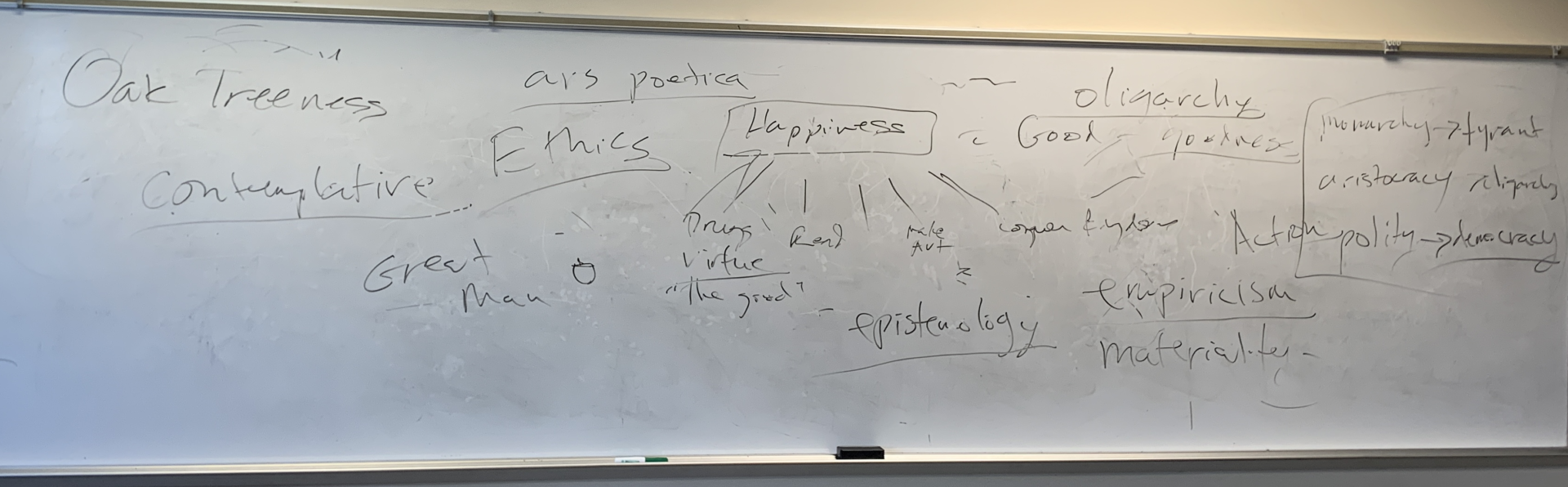

Anyhow, as you can see from the image here, I erased what I had written on the whiteboard about Plato and started over with Book One of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and a short reading from Plutarch on the life of Alexander (that’s why “Great Man” is written on the board two weeks in a row).

Aristotle’s and Plato’s ideas of the good, Feb. 13, 2020

But Platonic thought is represented to the left of the illustration – we have “Oak Treeness” as a (compound) illustration of the idea of the Platonic forms we had just discussed. But there on the board, just beneath the word Ethics, is a little drawing of an acorn. And that’s the difference between Plato and Aristotle, in a nutshell, as it were: either the things we see are figments and shadows of the purely Real that only those who spend a lifetime of searching for truth can hope to dimly see, or the things we see – and the people we are — hold within themselves the potential to become what they ought to be and will do so if at every step they are afforded and seek only what is to their good. We seek lesser goods (examples given were sex, drugs, reading, conquest) because we believe they will lead to happiness, which is the aim of life, but only they who are completely good can be completely happy, so that the ultimate aim of life is goodness itself — not a goodness we seek through contemplation, but one we cultivate and train ourselves towards through right action.

The dialectic between these two approaches to history and these two schools of thought in philosophy should keep us busy for the rest of the semester. We’ll come to Plato again in Saint Paul and Augustine (and beyond), and we will meet Aristotle in the medieval university and the Baconian laboratory (and beyond). As for Herodotus and Thucydides, they sit on my shoulders every class like little invisible squirrels, chattering and chasing each other around the tree-trunk of time. Just don’t ask me what side of the tree they’re on at any given moment.

_____

*I think if you right-click the photos and open them in a separate tab you can zoom in on them. Good luck reading my handwriting though!

0