Sarah Churchwell is a professor of American literature, and in Behold, America: The Entangled History of “America First” and “The American Dream,” she draws beautifully on classic fiction as well as the detritus of popular culture to flesh out the two concepts of the book’s subtitle. She frequently approaches political speech, however, in a rather different way. I don’t intend to review the book as a whole here (although I am going to do that down the road), but I found some of the book’s methodological procedure and tacit assumptions questionable in a way that I believe (or hope, at any rate) will prove useful and interesting to the readers of this blog. (If a blog is not the place to nerd out over methodology, what is it good for?)

There is a tendency among historians to treat political speech of the past as something upon which we are eavesdropping or intruding. This is particularly—I would almost say exclusively—true for political speech with which we disagree. Politicians or demagogues advocating for policies or ideas we find abhorrent are approached as if they were speaking before a closed circle of like-minded supporters, or as if they were speaking deliberately out of both sides of their mouth, hiding their meaning in keywords which kept them safe from contemporary disapproval.

Here is an example from Churchwell, writing about the 1916 Presidential election:

Here is an example from Churchwell, writing about the 1916 Presidential election:

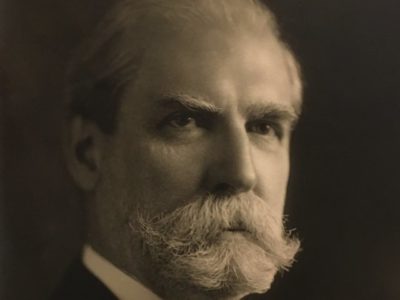

In his speech, [Charles Evans] Hughes announced: ‘I am an American, free and clear of all foreign entanglements,’ a deeply coded statement – what today we would call a dog whistle.

Saying that as an individual he had no ‘foreign entanglements’, Hughes was invoking a ubiquitous justification for isolationism, which held that in George Washington’s farewell address of 1796 he had warned America against ‘all foreign entanglements’…

[Hughes was] covertly reassuring his audience that he was not a ‘hyphenate’, which meant ‘one hundred per cent American’, which meant a native-born white Protestant.

The idea of ‘one hundred per cent Americanism’, as it was frequently called, itself began as a code for debates about ‘hyphenate’ Americans versus ‘pure’ Americans, before rapidly evolving into ways to suggest – without specifying – other kinds of ‘un-American’ people or behaviour.

Is this a dog whistle? Perhaps in the sense that some Americans did not know the origin of “foreign entanglements” (which Churchwell points out is a misquotation anyway). But a dog whistle is not really the correct word for people not getting an allusion. For even if some Americans may not have known that Hughes was trying to invoke Washington, the purpose of his statement would have been clear to him—the same nativist purpose that Churchwell reveals as “a code.”

Here is how Churchwell defines “codes.”

Soon it became impossible to disentangle the codes – which is one of the points of deploying them. Codes create plausible deniability, and not merely in public. They can also give people who use them a way to evade their own cognitive dissonances. The codes are there to muddy the waters, to keep people from seeing their own faces in the pool.

Whose face, we might ask, was Hughes interested in distorting? Why would he want or need plausible deniability? In 1916, what was the point of trying to avoid being considered a nativist?

I am not being flippant in asking these questions: they are essential questions for thinking about how we interpret political speech from the past. Nor is this merely a question of proper contextualization—asking if Hughes’s statement was excessively nativist for its moment and therefore plausibly needed to be cloaked in code.

Churchwell’s book is largely about how very public and unabashed nativism was for most of the first half of the twentieth century. It was an out-of-doors politics, a politics of parades and grandstands, and a politics of earnest openness—of letters to the editor and hearts (or swastikas) on sleeves. Why, then, would she spend time decoding a language that was, so to speak, so ostentatiously unencrypted?

Obviously, the people who need interpretive glosses about “foreign entanglements” or any of the other “dog whistles” or “codes” are Churchwell’s present-day readers—not the people who witnessed these events firsthand. For them, no intermediation, no translation was necessary because politicians had no desire to and no reason to hide their nativism. What makes these politicians’ speech seem to lack transparency to us today is simply the ordinary passage of time and the normal erosion and replacement of political landmarks. Politicians like Hughes were not

, in short, trying to be esoteric.

The impulse to decode political language has become, I think, a reflex for citizens: we expect a steady stream of euphemisms and evasions if not outright lies from our political leaders, and we have taken on the necessity of vigilance as an inevitable part of everyday life. I think part of this has been heightened or exacerbated by the Global War on Terror, although frankly I don’t remember enough about political life before the GWOT to be able to compare adequately. But it is important to specify what this impulse is: it is not, necessarily, a desire to investigate, to unearth things that are actually out of sight; it is, instead, an urge to see things that we believe to be camouflaged but sitting right in front of us.

But part of our decrypting impulse is also, perhaps, a product of the methodological paranoia inherent in the “hermeneutics of suspicion.” Especially for those of us with any training or prolonged exposure to the literary theory of the 1980s and 1990s, this is a basic part of our reading toolkit—the belief that there is a subtext, the mandate that we pierce through the surface of the text in order to throw off its ideological façade. It is difficult not to see all

language as a kind of code when one has been brought up in the High Church of Theory.

Yet I do not think the matter is easily resolved by a little quick metacontextualization—by historicizing our own reading practices. There is a more general methodological problem that this particular issue lays bare: how closed-off from us is the political speech of another time? If we are not eavesdroppers or intruders upon the scene of a political statement like Hughes’s, then what is the proper name for our relation? How do we quickly and seamlessly convey for our readers a world of references and shorthand that was second nature to others in the past without making it seem like the language being used was a kind of code?

To be precise: this is not a problem of our understanding a given text from the past, but of our ability to render that understanding to a third party—to our readers. I Thus, I am not sure that many of the classic methodological statements of intellectual history are much help here, as they tend to focus less on that second step and much more on the first step—on how to reconstruct and interpret the context of a historical speech act for ourselves.

But perhaps the underlying issue is ultimately the still standard way intellectual historians tend to think of context, and even of the past itself. In “Contextualism and Criticism in the History of Ideas,” a terrific article in the essay collection Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, Peter E. Gordon notes that there is a basic contradiction (perhaps paradox is the right word) in the way historians think of the work that we do:

On the one hand we tend to think of history as an exercise in reconstruction: because we are prone to think of the past as a foreign country our chief aim is to rebuild for ourselves its language and its customs while keeping in mind that this world was quite different from our own. But on the other hand we think of history as a discipline that is devoted primarily to the study of change: it is not the past as a location that arouses our interest but the past as passage or transformation. Our very understanding of historical inquiry therefore seems to involve two concepts of time: time as a series of moments (punctual time) and time as the extension between them (differential time). (Gordon 2014, 33-34)

We are constantly torn, in other words, between, on the one hand, our desire to emphasize the distance and strangeness of the past from our present and, on the other, our desire to illuminate the ways that the past changed over time into our present. We are caught in a historical equivalent of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle: if we grab hold of the past for long enough to establish the particulars of its position—to reconstruct the internal world of its meanings and references—we lose the ability to capture its velocity, its arc of movement. But if we seek to measure its speed in full flight, we have to give up on knowing a precise location.

Is it the case, then, that it is impossible to hold the diachronic and synchronic together? That we cannot emphasize both the pastness of the past and its development—its constant transformation into something else—at the same time? Perhaps what I am looking for is something like simultaneous translation, where the interpreter begins translating the speaker’s last sentence even as they begin listening to the one being spoken that moment. Simultaneously listening and speaking: a tough job to pull off!

0