As I’ve argued here before, there’s no better window into the world of mid-18th century Philadelphia than Ben Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette. Any single number of Franklin’s paper promises innumerable avenues of approach to understand the rich texture of daily life. In fact, the same number that I wrote about here at the blog before still yields a rich vein of material I can continue to mine in my teaching. Three years later, I’m still using the same number of this newspaper to teach the U.S. history survey, and I’m still finding new things to talk about.

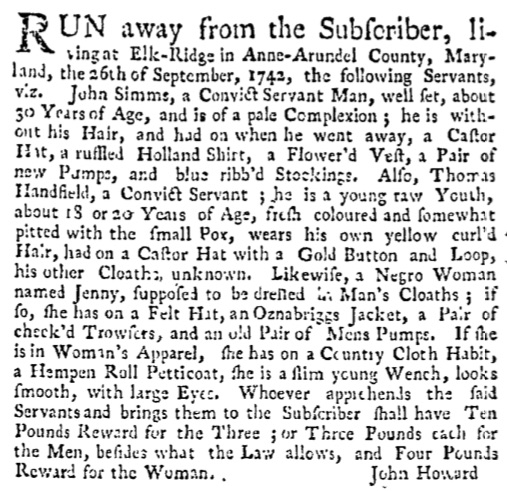

Let’s take this advertisement, for example, found on page four of the newspaper of November 18, 1742:

Run away from the Subscriber, living at Elk-Ridge in Anne-Arundel County, Maryland, the 26th of September, 1742, the following Servants, viz. John Simms, a Convict Servant Man, well set, about 30 Years of Age, and is of a pale Complexion; he is without his Hair, and had on when he went away, a Castor Hat, a ruffled Holland Shirt, a Flower’d Vest, a Pair of new Pumps, and blue ribb’d Stockings. Also, Thomas Handfield, a Convict Servant; he is a young raw Youth, about 18 or 20 Years of Age, fresh coloured and somewhat pitted with the small Pox, wears his own yellow curl’d Hair, had on a Castor Hat with a Gold Button and Loop, his other Cloaths, unknown. Likewise, a Negro Woman named Jenny, supposed to be dressed in Man’s Cloaths; if so, she has on a Felt Hat, an Oznabriggs Jacket, a Pair of check’d Trowsers, and an old Pair of Men’s Pumps. If she is in Woman’s Apparel, she has on a Country Cloth Habit, a Hempen Roll Petticoat, she is a slim young Wench, looks smooth, with large Eyes. Whoever apprehends the said Servants and brings them to the Subscriber shall have Ten Pounds Reward for the three; or Three Pounds each for the Men, besides what the Law allows, and Four Pounds Reward for the Woman. John Howard

Where to begin?

First, the mention of “convict servant” men allows for a discussion of the various forms of unfree labor that existed side by side in colonial America. Because these men were not designated by ethnicity or race (as opposed to an “Irish servant lad” and “Negro men” mentioned in advertisements in the same number of the newspaper), they are presumably white Englishmen – two of about 60,000 convicts who were shipped to the American colonies as indentured servants under the Transportation Act of 1718. Such men had fixed terms of indenture, and these two men apparently still had time to serve.

And what kind of men were these two?

Maybe a little finely dressed, as convict servant men go. A ruffled shirt, a flowered vest, new pumps, blue stockings for the one, a gold-trimmed hat for the other – that John Howard, the advertiser, knows for sure. The fact that he doesn’t know what else the younger man might be wearing is interesting. Did John Simms run away in John Howard’s clothes – thus the detailed inventory – while the “young raw Youth” with “his own yellow curl’d Hair” lifted a wardrobe off of someone else’s clothesline? How else would John Howard know that it would be Thomas, and not the bald John Simms, wearing the gold-trimmed hat? Would he know that Thomas always wore the hat but not be sure of what else Thomas always wore? Did Thomas leave behind his own clothes (save the hat) when he ran away? In what circumstances might this transpire? Were his own clothes so distinctive that they would be easily recognized if described?

Speaking of distinctive attire, let’s think for a moment about the “Negro Woman named Jenny” who fled with the two indentured servants. Jenny is not described explicitly as an enslaved woman, and she may have been a servant instead. The language at the end of the ad – “whoever apprehends the said servants…” – is boilerplate language in these runaway ads, and may have included both indentured servants and enslaved servants. By the same token, “for sale” notices in this number of Franklin’s paper distinguish between a “servant woman” with three and a half years of her contract left to serve and a “Negro woman” of whom no contract length is mentioned. So I am inclined to think that Jenny was enslaved, especially because she has no last name.

And I am inclined to wonder how and why John Howard knew how Jenny would look both “in Man’s Cloaths” or in “Woman’s Apparel.” He knew what John Simms was wearing, ruffled shirt and flowered vest and all, and he knew that Thomas took his fancy hat with him. But Jenny had two outfits, equally familiar to John Howard from crown to sole. What can this mean?

It could mean something as simple as this: an outfit of the same size that the slender Jenny might wear went missing when she did, and John Howard put two and two together and realized she was trying to disguise herself.

But it could also mean that John Howard knew that Jenny could pass as a man and had seen Jenny do so before.

When I discussed this advertisement with my classes, I told them that we really can’t know which of these two scenarios is more likely. But I told them that we can read this as an indicator that gender fluidity and gender bending – whether for disguise or for daily life – are not recent developments in human experience, even if our way of talking about them is new.

While it would be ahistorical, I think, to identify Jenny as a transgender person, it would be ahistorical not to make that claim, or at least it would be ahistorical to fail to recognize it as a real possibility. How do we describe in the terminology of our own time the lived experience of Jenny in her time? Was Jenny a transgender man? A frequent cross-dresser? An occasionally gender-bending cis woman? We will never know.

We do know that John Howard offered 3 pounds each for the men, and 4 pounds in reward money for Jenny – again, probably an indication that she was regarded as his legal property for life, and so was worth more to him over the long run than two servants with fixed-term contracts.

But that reward amount is high indeed compared to all the other rewards for runaways offered by various advertisers in this number of Franklin’s paper, whether they are “Negro” men or “servant” men.

There was something special about Jenny that made her more valuable than the fresh-colored raw young youth with a handsome head of curly blonde hair. That something special may simply have been her economic value as a life-long laborer, or her reproductive value as an enslaved laborer who would bear offspring that would be the legal property of John Howard. Or — and? — that something special may also have been whatever gratification John Howard derived from Jenny’s ease in self-presentation and performance as either a woman or a man.

Whatever the case, I hope that Jenny, with their large eyes and their smooth skin and their slim frame, was able to draw on that something special to run far, far away and dress and live however they pleased.

0