Editor's Note

This is the sixth post in a series that uses the study of nineteenth-century Dutch immigrant settlements in Iowa, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin to pose larger questions about how the international consciousness of rural communities in the nineteenth century challenge not only our understandings of the rural Midwest, but also of conceptions of American and European imperialism, settler colonialism, and worldwide missionary efforts.

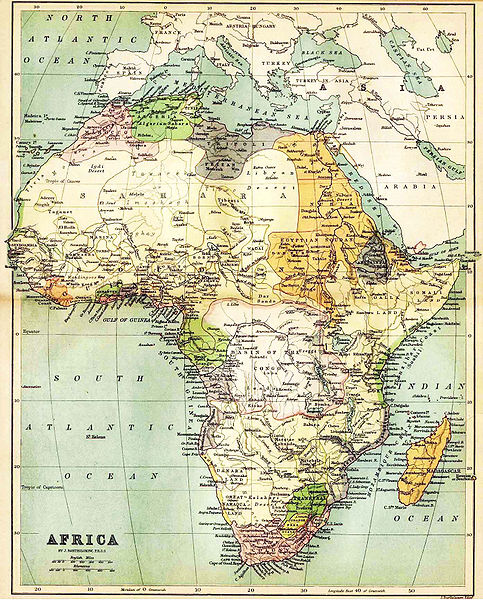

In the late nineteenth-century, when rural Midwesterners looked out into the world, they spoke with specificity about many nations and the people who lived in those places. In the small Dutch-American community of Holland, Michigan, which has been a case study throughout this series, perspectives were influenced by their own imperialistic and evangelistic aims, and in their writing they carefully distinguished between nations like China, Japan, Korea, and India. Conversely, when they looked to Africa, they spoke with little specificity. Aside from Egypt, which was most frequently discussed with reference to its ancient history, they talked about Africa in general terms that reflected racial stereotypes and a dearth of knowledge about the differences within the continent.

Unlike Asia, these rural Midwestern communities had few direct connections to Africa. The international students in their communities hailed from Japan or the Netherlands, and at the time, they only sent missionaries to China, Japan, and India. Rumors of the annexation of Hawaii, the purchase of Alaska, and rumblings of North Pole expeditions kept the other regions discussed in this series in the news. Africa, on the other hand, remained more mysterious to them. The only direct communication they received about the continent came from occasional letters from other Dutch expatriates living in South Africa. This lack of information made it easier to treat Africa as a monolith and apply the racist and imperialistic attitudes prevalent within broader white culture in the United States at the time to the entire continent.

They did not think internal differences within Africa were particularly significant.

In general, men and women in this rural Midwestern community did not speak with any specificity about Africa, and there is no evidence that they thought that they needed to do so. In other writings, they took the time to differentiate between Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese culture and discussed distinct polities within Asia. They spent little time exploring Africa with any attention to the different cultural, linguistic, and political groups. Instead, they tended to discuss all Africans collectively. They did, however, note that most Africans, particularly in the northern parts of the continent, practiced Islam and groups throughout other regions practiced a mix of local religious traditions.

[1] For these evangelistically minded rural men and women, it makes sense that one of the few distinctions they made focused on religion.

The major exception to this lack of interest in diversity within Africa was South Africa. These rural immigrants demonstrated a clear knowledge of ethnic groups within the country as well as the tensions that simmered among the Dutch-descended Boers, the British, and the local African tribes. The Dutch Empire had enjoyed a foothold in South Africa for centuries by this point, and though they had lost their colony to the British, the lingering connection within the Dutch diaspora was apparent.[2] This specific interest in South Africa reflects a well-established communication network between Dutch-descended communities throughout the globe, including Holland, Michigan and other Dutch colonies throughout the rural Midwest. Such attention to detail in South Africa further highlights the broader disinterest in speaking in a nuanced way about the rest of the continent.

They argued that Africa’s climate affected the character of the people who lived there.

These rural settlers had a different explanation for their lack of knowledge about Africa. “The reason why so little is known of Africa,” explained B. Pijl, “is owing a great deal to its burning climate and hostile inhabitants.”[3] These Westerners’ ignorance, in his estimation, was actually the fault of the Africans and their environment. A careful reading of writings from this community at this time reveals that adjectives like “burning” and “tropical” carried significant implications that extended far beyond simply describing the weather.

Throughout the final decades of the nineteenth century, several essays discussing the serious implications of climate on the character, industriousness, and intelligence of human beings appeared in a local periodical, The Excelsiora. The authors outlined a clear position: hot, tropical climates created lazy people who squandered their natural gifts and abilities.[4] Warm climates, they insisted, made people enervated, indolent, and vicious.[5] Descriptions of a region’s climate, consequently, ascribed certain qualities to its inhabitants.

J. G. Rutgers outlined this logic explicitly: “In the Tropics we find the inhabitants generally ignorant and uncivilized. This is mostly the result of the climate to which they are subject. Excessive heat enfeebles them, and it invites them to repose and inaction. They abandon themselves to the external influences, submit to the yoke, and become again the animal man, forgetful of their high moral destination.”[6] Rutgers later made clear that in his view the Tropics included the entirety of Africa.

This understanding of the effects of climate, therefore, buttressed racist stereotypes that pervaded society at the time. It provided these rural settlers with an explanation for their beliefs about Africans. By speaking broadly about the entire continent, they did not need to note Africa’s different climates but could instead apply racist and dehumanizing caricatures to the inhabitants of an entire continent.

They portrayed Africans as violent, uncivilized, and ignorant.

Undergirded by racist interpretations of the climate’s effect on human beings, essays on Africa appeared in the community, and they frequently played into prejudiced stereotypes, further dehumanizing Africans.

In a fictional story about a visit to Africa, Henry Giebink described the dwellings of Africans as fit only for muskrats and beavers—again directly linking Africans to animals. He imagined receiving an invitation to come to dinner from a local family. Though he accepted out of a desire to be courteous, Giebink remarked, “I went along, but with fear and trembling, for I was afraid that, if once inside, instead of dining with them, they would dine on me.” Once at the dinner, he described the table manners of the family as fitting only for a hog pen. The story presents Africans as violent, potential cannibals who lived and behaved like animals. Any positive attributes that Giebink noted about Africans reflected his presumption that the entire population of the continent lived in a state of childlike ignorance. This story carries problematic conceptions of the effects of topical climates on the people who live in them to their logical end.[7]

The racist conceptions of the effects of climate did not simply produce generalizations about the characteristics of Africans within this rural community. It justified specific racist ideas about the behaviors of Africans in ways that furthered narratives of Africans being dangerous and regressive.

Ideologies about race and climate coupled with broad generalizations supported a racist vision of Africa in this nineteenth-century rural community. Discussions about Africa and Africans lacked nuance, unapologetically ignored Africa’s diverse linguistic, cultural and political groups, and ultimately, deployed faulty ideologies to justify the application of racist stereotypes to the population of the entire continent. In this way, understanding this community’s international consciousness further opens windows into the intellectual life of rural Midwesterners, the racist ideologies that they employed when forming their worldview, and the consequences of such thinking.

[1]B. Pijl, “Africa,” The Excelsiora 7, No. 11 (April 1877).

[2]A. Leenhout, “Foreign Affairs,” The Excelsiora 15, No. 2, (November 1885), 89.

[4]J.G. Rutgers, “Life in the Tropics,” The Excelsiora 10, No. 9 (March 1880), 290-91.

[5]“Does Climate Affect the Character of a Person?” The Excelsiora 5, No. 7 (February 1875), 308.

[7]Henry Giebink, “Foreign Correspondence: South Africa,” The Excelsiora 15, No. 8 (March 1885), 334.

0