In the first chapter of The Making of the Modern University, Julie Reuben remarked that Francis Wayland’s Elements of Moral Science, first published in 1835 and still in print well after the author’s death in 1865, was “America’s most popular moral philosophy text.”[1] By that I think she means that Wayland’s text was the most frequently and widely assigned textbook for moral philosophy classes, usually a capstone course in the traditional four-year bachelor of arts degree program.

These classes were often taught to college seniors by the school’s president, and they were meant to help students synthesize and to some degree harmonize all they had learned in their previous years of study into a unified whole. As Reuben’s work shows, the moral philosophy course as a capstone course faded from the curriculum as the emerging modern sciences both multiplied the fields of study young scholars were expected to master and challenged the notion that the knowledge yielded in these new areas of research either could or should be “reconciled” somehow with moral truths, particularly with Biblical truths of a literally-interpreted scripture.

These classes were often taught to college seniors by the school’s president, and they were meant to help students synthesize and to some degree harmonize all they had learned in their previous years of study into a unified whole. As Reuben’s work shows, the moral philosophy course as a capstone course faded from the curriculum as the emerging modern sciences both multiplied the fields of study young scholars were expected to master and challenged the notion that the knowledge yielded in these new areas of research either could or should be “reconciled” somehow with moral truths, particularly with Biblical truths of a literally-interpreted scripture.

But for a while – thirty or forty or perhaps even fifty years? – Wayland’s book was the standard work assigned in these undergraduate capstone courses.

As college professors (and students) well know, what is widely assigned is not always deeply read, if it is read at all.

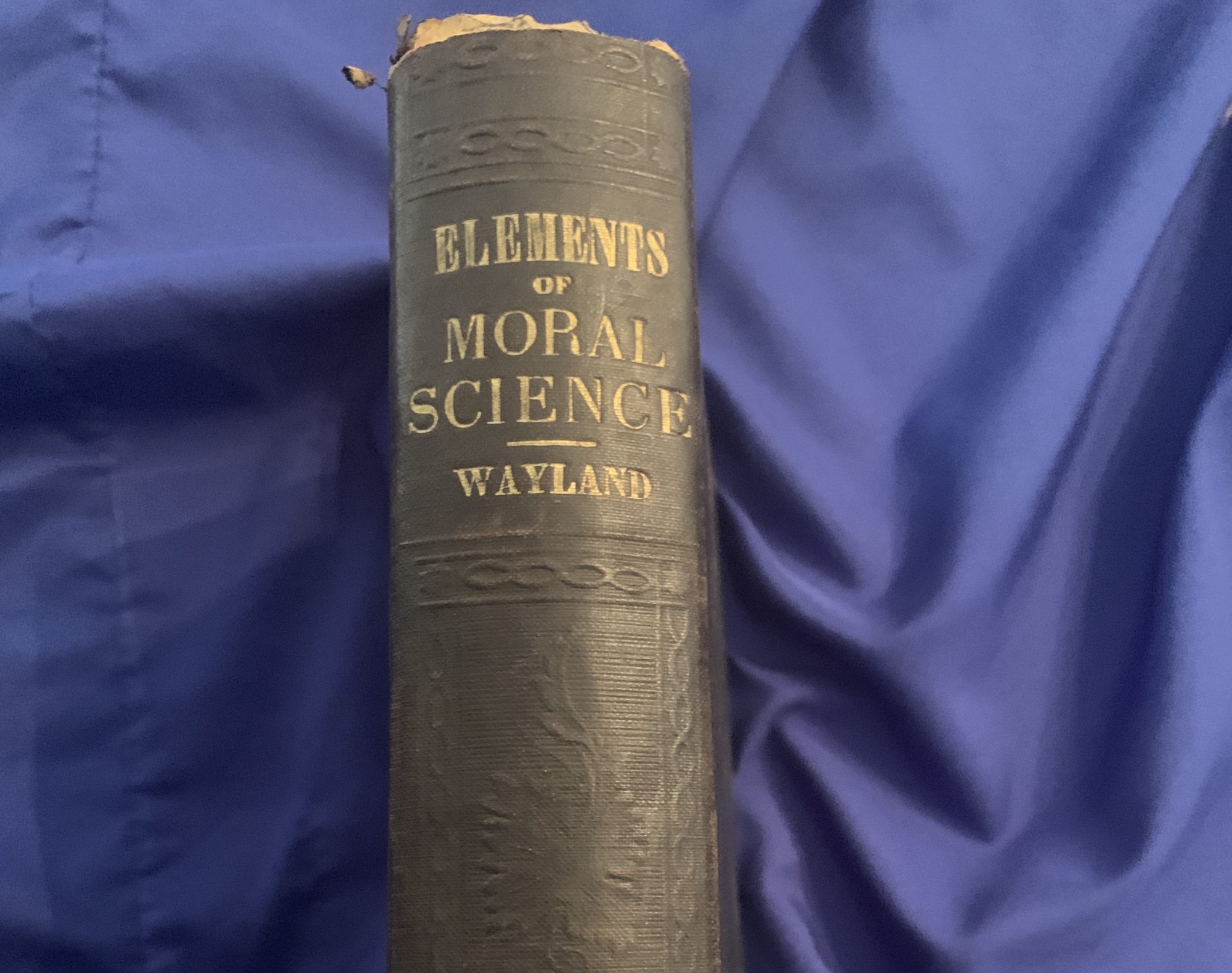

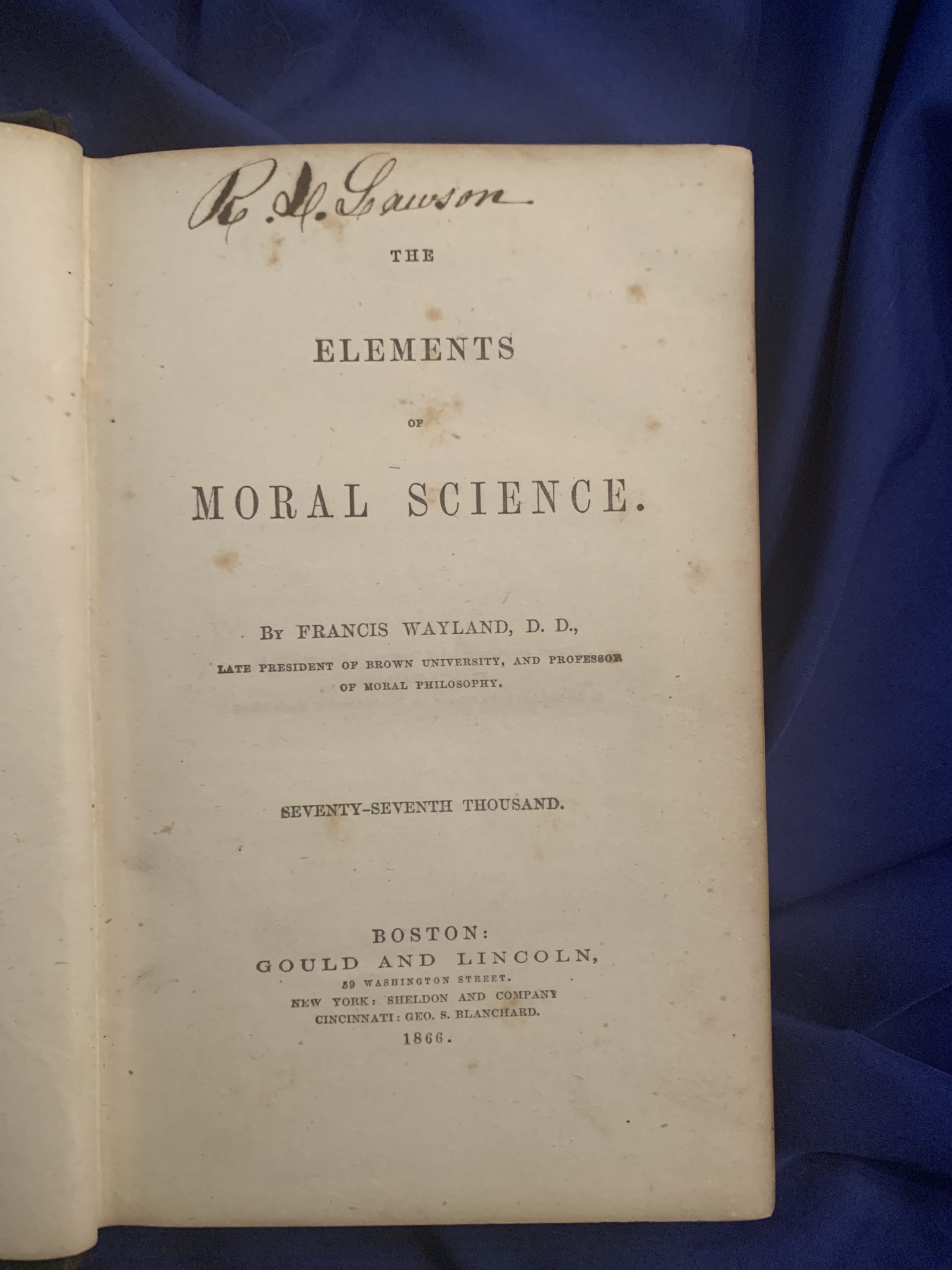

A while back, I purchased a gently used copy of The Elements of Moral Science. This particular edition was published in 1866, a year after Wayland’s death, and this copy has held up very well over the years. It was read very little – which is why it is in relatively good shape today. The more well-read and heavily-annotated copies of Wayland’s book (and there must have been thousands of such copies) probably haven’t survived for 150 or 175 years since they were first published and purchased, used then perhaps passed along to the next generation of students. Sometimes it is not the best loved but the least loved books that come down to us.

A while back, I purchased a gently used copy of The Elements of Moral Science. This particular edition was published in 1866, a year after Wayland’s death, and this copy has held up very well over the years. It was read very little – which is why it is in relatively good shape today. The more well-read and heavily-annotated copies of Wayland’s book (and there must have been thousands of such copies) probably haven’t survived for 150 or 175 years since they were first published and purchased, used then perhaps passed along to the next generation of students. Sometimes it is not the best loved but the least loved books that come down to us.

This copy of Wayland does show some signs of use and some signs of sentimental value. Someone who owned this book pasted a popular and oft reprinted poem on the flyleaf, a meditation on mortality whose first stanza begins, “Behold this ruin! Twas a scull…” You can read the full poem here in an 1821 number of The National Recorder, a Philadelphia magazine that reprinted plenty of material from other publications, sometimes with attribution. The poem was reprinted many times throughout the 19thcentury, under various titles, and the spelling in the first line was frequently modernized to “skull.” This particular clipping was cut out from some newspaper or magazine printed on rag paper, and the poem is a fine example of the moralizing sentimentalism about mortality, so common in the 19thcentury, meant to turn the reader’s thoughts to a life of virtue. It is in some ways a perfect clipping to paste between the covers of Wayland’s book.

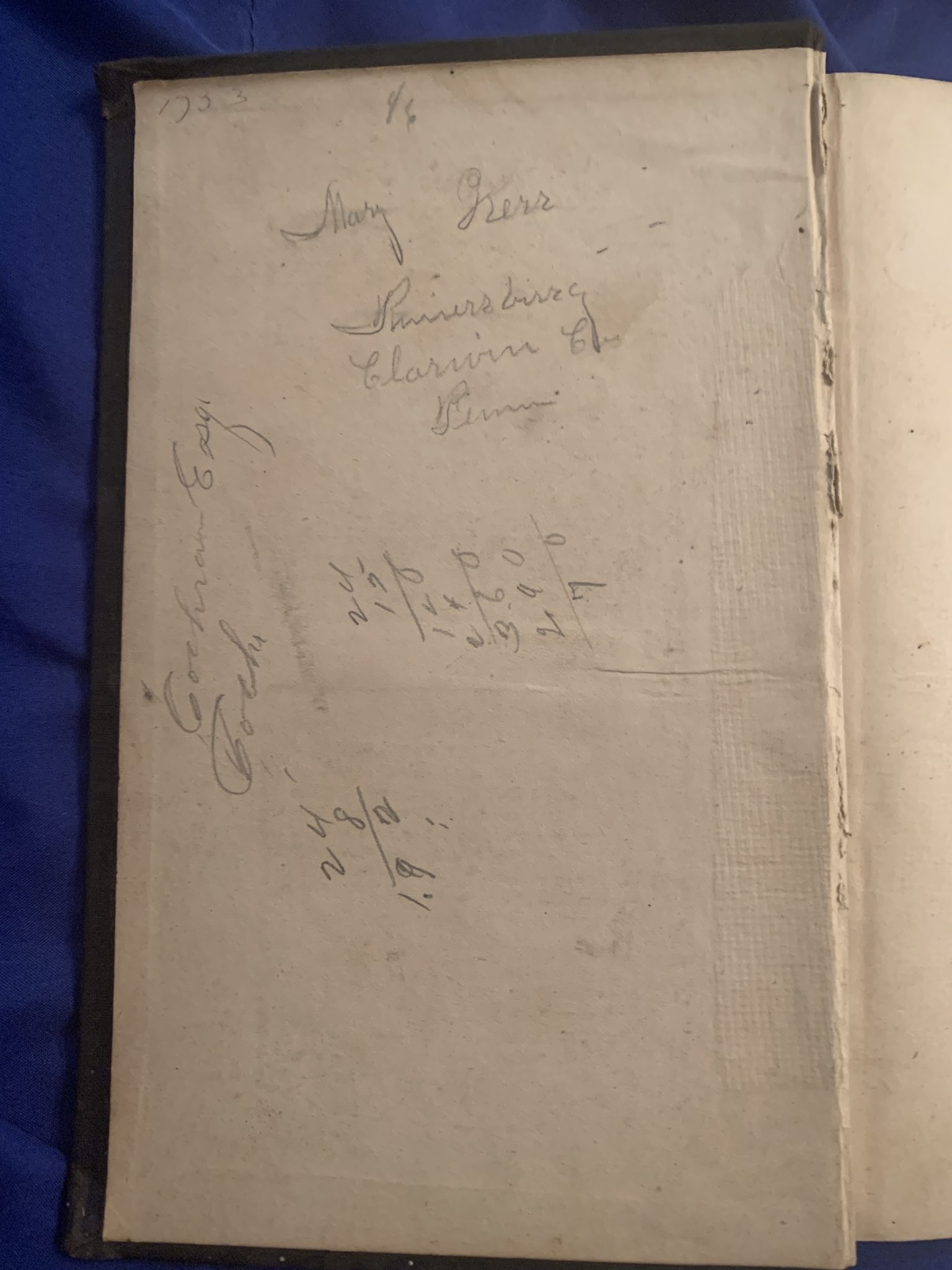

This copy had perhaps three different owners, for there are three different names written in various places inside it. There is a bold signature atop the title page – the first initial is R, the middle initial is maybe an H (?), and the last name is Lawson. Another name in the book, written in pencil on the front endpaper, is clearly legible: Mary Kerr. And that name is followed by what appears to be an address (far less legible) that ends with the abbreviation “Tenn.” And then someone else entirely seems to have been practicing his signature in pencil on the same endpaper – “Cochran Esq.”

This copy had perhaps three different owners, for there are three different names written in various places inside it. There is a bold signature atop the title page – the first initial is R, the middle initial is maybe an H (?), and the last name is Lawson. Another name in the book, written in pencil on the front endpaper, is clearly legible: Mary Kerr. And that name is followed by what appears to be an address (far less legible) that ends with the abbreviation “Tenn.” And then someone else entirely seems to have been practicing his signature in pencil on the same endpaper – “Cochran Esq.”

Beneath that signature is some math. There are two problems. One is a simple multiplication problem. The other is a multiplication problem followed immediately by a subtraction problem. The decimals in the results mark values in hundredths, so I’m guessing that what was being multiplied and then subtracted was money. And what other kind of math would you expect for a fellow who was testing the look of a distinguished title behind his name?

There’s just one penciled annotation in the published text itself. In this, the most widely assigned moral philosophy book in the mid-19thcentury, there is but one mark. It’s just a little bracket in the margin of page 29, embracing a single salient paragraph, with a horizontal line stretching toward the edge of the page for added emphasis. Here is the paragraph this unknown reader singled out for contemplation:

If the question, then, be asked, what is a moral action? we may answer, it is the voluntary action of an intelligent agent, who is capable of distinguishing between right and wrong, or of distinguishing what he ought, from what he ought not, to do.

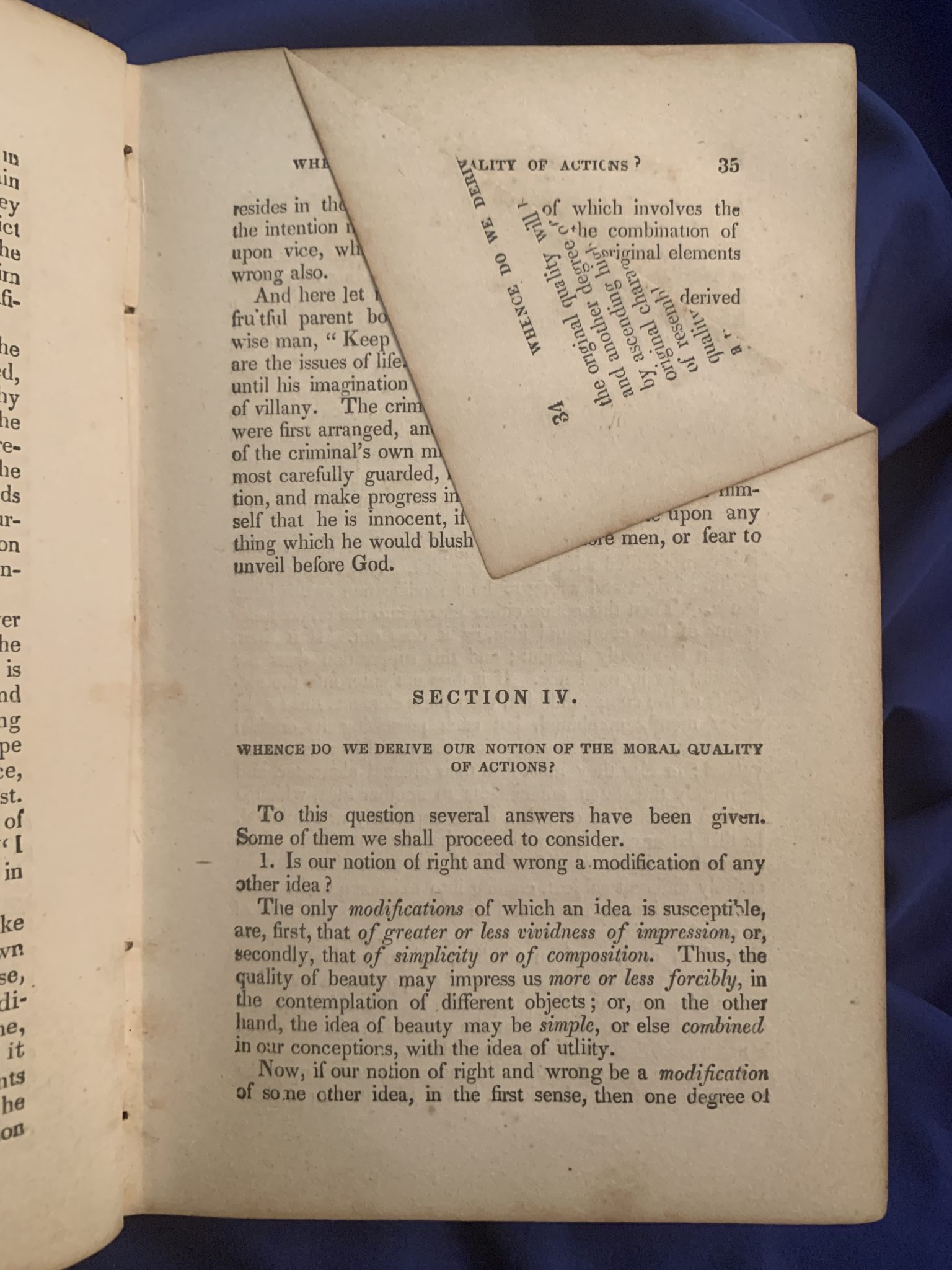

A few pages later, there’s a deeply folded dogear that has remained undisturbed for perhaps 150 years. The facing page, and many pages before and after it, are foxed at an angle corresponding to the borders of that folded corner.

I unfolded it to read what was printed on the page beneath. Here it is:

And here let me add, that the imagination of man is the fruitful parent both of virtue and vice. Thus saith the wise man, “Keep thy heart with all diligence, for out of it are the issues of life.” No man becomes openly a villain, until his imagination has become familiar with conceptions of villainy.

And so on.

There’s evidence of another dogear that was folded back and set aright some time ago, this time on page 267:

What would become of families, of friendships, of communities, if parents and children, husbands and wives, acquaintances, neighbors, and citizens, should proclaim every failing which they knew or heard of, respecting each other?

What indeed?

These widely separated dogears and these penciled problems of money and these scattered signatures are the only traces left upon this book by the long-dead readers or possessors of its pages. That, and the pasted poem meditating upon a moldering skull:

….This space was thought’s mysterious seat.

What beauteous vision filled this spot!

What dreams of pleasure long forgot!

Nor hope, nor joy, nor love, nor fear,

Have left one trace of record there.

Thus endeth the lesson.

__________

[1]Julie Reuben, The Making of the Modern University: Intellectual Transformation and the Marginalization of Morality(Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 21.

0