After discussing the syllabus — which never takes even a full 50-minute class period for those three-day-a-week sections, and leaves almost the full class period for two-day-a-week classes — I spend the whole first week of every semester on an introduction to the discipline of history as a field of knowledge.

I have students read an excerpt from Thomas Haskell, and we discuss that and establish some ethical expectations for ourselves as part of a community of inquiry. I ask them how we can know what we know about the past, and how we can know that historians who are telling us something about the past are getting it right, or at least right enough. And we talk about that, using some of my favorite ten-dollar words (when I was a kid, we called these “50 cent words,” but I don’t think that would sound like a lot to college students today): epistemology, nomothetic, idiographic, forensic.

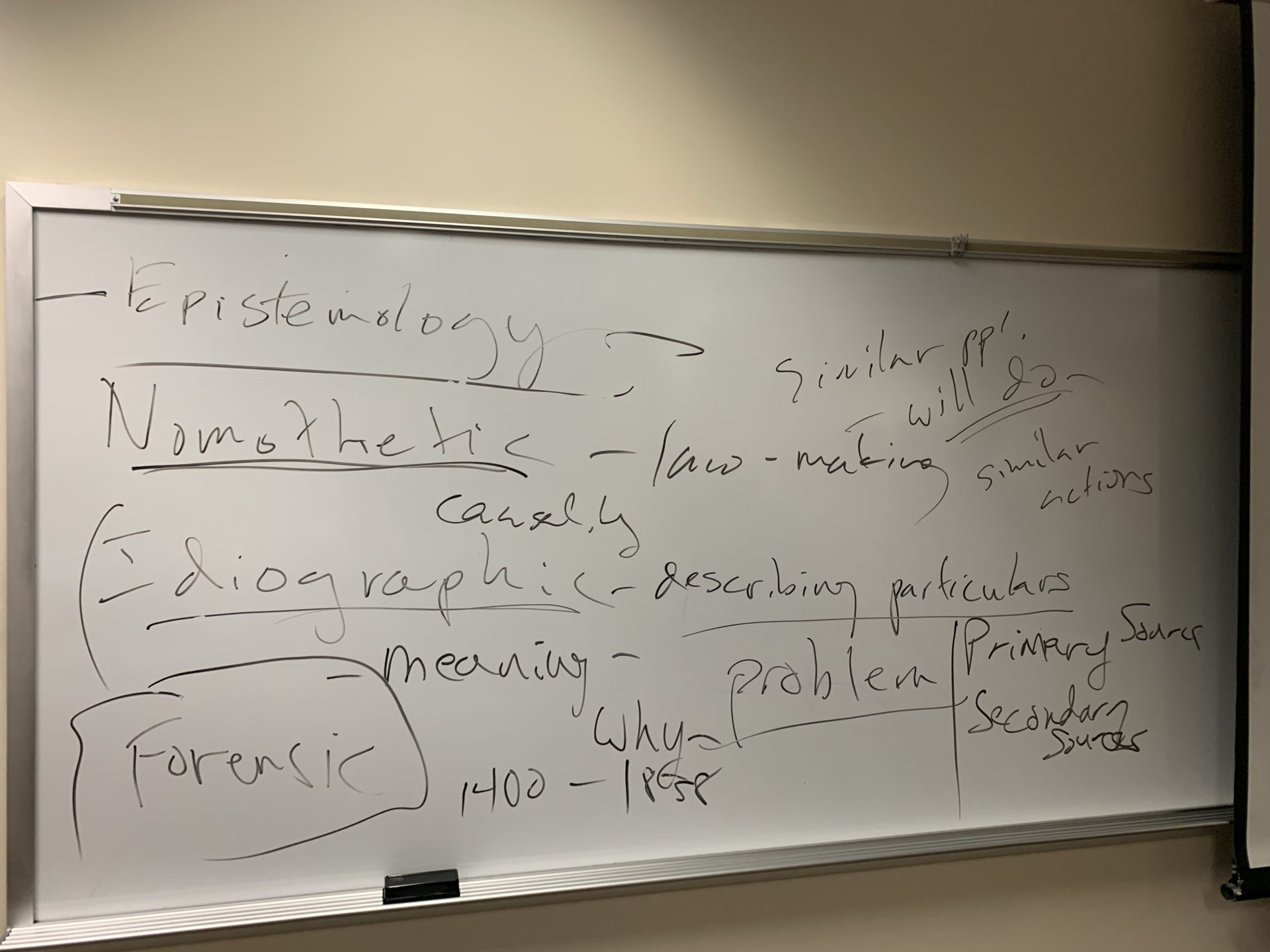

Here’s a glimpse of part of the whiteboard from yesterday’s class.

I usually choose chemistry as the nomothetic discipline under discussion, because it is a lab science that many students have had some experience with in junior high or high school or college. We talk about what students are expected to learn when they do lab experiments, and what they’re not expected to learn. They usually volunteer that they are expected to learn technique, or to demonstrate “the laws” of the discipline they’re studying, “how chemistry works,” and so forth.

“Wait,” I say, “doesn’t anyone expect you to discover a new element in the periodic table in your high school chemistry class?” They laugh. Then I say, “Well, what is the point of calling it an experiment then, if it is something that has been done before by someone else?” The students always come up with good reasons for doing labs, and I sum up their reasons thus: the point of the experiments is to learn how knowledge in the field of chemistry is generated, verified, demonstrated, and communicated. With every lab there is a lab report: the materials you used, the conditions under which you ran the experiment, the steps you took, the results you got, an explanation of the results. All of this may communicate new knowledge to the student, but it also communicates a way of knowing and a procedure for verifying what someone else says they know.

One of my students this week suggested that history can be thought of as operating according to laws, maybe not exactly like chemistry, but close, because “similar people will do similar things.” You can see from my pic of the whiteboard that I underscored “will do” and we all discussed whether that was a diagnostic observation or a predictive claim. Under whatever controlled conditions the lab experiment calls for, chemical substances will react the same way every time. You can predict it; you can expect it. If you can re-create those conditions – re-run the experiment – you will get the same results.

We then discussed why it is that history cannot be predictive, why studying what people have done in the past cannot tell us what they’ll do in the future: people gonna people. Human will is the variable for which we can never fully account. Set human will upon the flying arrow of time, and the conditions of the great experiment of the human past change with every life, with every moment. We historians can only say with confidence what people in that

time, in that place, in those circumstances believed they were doing, or tried to do, and what that outcome was. We can only describe particulars — we are the idiographic discipline par excellence. There is no re-running the experiment to verify the hypothesis or reproduce the results, because every human experiment – every life, every choice – alters, however slightly, the conditions that follow. Even if we had full understanding of every yesterday, we cannot say for sure what tomorrow will bring.

So then we talk about what the use of history might be if it is not any good for predicting the future. Of what use is history’s way of knowing? And how can we know that a historical claim is sound? How do we test the claims of historians? How can we trust our textbook? How can you trust your professor?

And then we talk about that – and about some other things, as you can see from yesterday’s whiteboard scrawl.

It’s a lot for the first week of class. The arrow of time flies fast indeed on a semester calendar, and I already feel behind. (I don’t even know how you teach U.S. history on a quarter system – do you divide it into thirds?) But I take my time at the beginning of the semester to frontload these ideas and questions and epistemological conundrums and ethical expectations – the expectations I have for myself, the expectations students can have for me and for each other. I want them to know that I take them seriously as thinkers, and I want them to take themselves seriously as thinkers. Because the American past is serious business these days – contested, fraught, instrumentalized and leveraged by various people for various purposes, invoked to justify violence, invoked to call for violence’s end. So we should know what we’re getting into, and understand how we’re going to go about getting into it, before we dive in.

I save the official diving in for week two. I’ll let you know how it goes.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I just discovered your essays, Mrs. Burnett. As someone who is just beginning to work in a History class – because i’m still doing my internship with teenagers -, i’ll be very glad to read more like that one.