David Byrne of Talking Heads. Photo by Plismo.

“Air can hurt you, too,” David Byrne sang on a record released forty years ago this month. The song was called “Air,” the album, Fear of Music, and the name of the band was Talking Heads. If one is to believe random internet commentary–claims often attributed to memory of some Byrne interview or another–this was not a song about air pollution.

No argument here. I would point out, however, that this song was made within a decade or so of the rise of modern environmentalism in the US, which was acutely attuned to the imagery of air that could hurt you–to photos of billowing industrial smokestacks and thick smog hovering over cities such as Los Angeles and New York. It was also a song recorded within weeks of the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, when one the facility’s reactors suffered a near-meltdown, and radioactive gases were vented into the atmosphere.

Good songs resist being reduced to prosaic readings. “Air” isn’t about air pollution. But it is a song that draws on the ecological imagination, the shift in the way many perceive the nature of reality and their relations with their surroundings. It is a song that partakes of historical context and events in which the ecological imagination took shape. And it is a song that speaks to the fear and dread that is, to my mind, one of the under-explored and under-theorized aspects of that imagination.

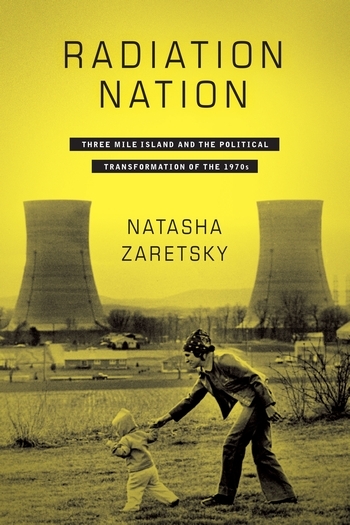

In her book Radiation Nation: Three Mile Island and the Political Transformation of the 1970s (Columbia UP, 2018), Natasha Zaretsky provides a case study in what I’ll call, for this post, environmental fear. The consciousness of our interdependence with the living world, our interconnectedness and our embeddedness in nonhuman life processes, is often associated with a commitment to universalism. When the Apollo photos, such as “Earthrise,” were published, people saw that they shared the same “lonely planet,” that we were all one, etc. But in the local response to the accident at Three Mile Island, Zaretsky reveals another aspect of the ecological imagination. To put it bluntly, the response was tribal. Trust, already weakened, broke down. In the end, universalist perspectives were rejected for the sort of resentment-based nationalism that we’re so familiar with today.

“What is happening to my skin?” Byrne sings. “Where is the protection that I needed?” The ecological imagination emphasizes the permeability of boundaries, not least skin boundaries. The fact that radiation poisoning was invisible and its effects gradual, for example, made it an especially insidious kind of bodily threat. The Three Mile Island community perceived itself, Zaretsky argues, as the heartland, as the true body of America. That body had been invaded. Sixties progressives had celebrated the body as a site of liberation and pleasure, but in the reaction to Three Mile Island, “conservatives folded the body into a discourse of decline and betrayal, creating a body politics of their own” (98). Zaretsky calls this “biotic nationalism.”

Some bodies were more vulnerable than others. Mothers, pregnant women, and children were the first advised to evacuate. In abstract terms, they represented what was most in peril–a society’s ability to reproduce itself. The symbols adopted by the movement came to reflect this. Biotic nationalism was “shot through with ecologically derived images of the vulnerable bodies of mothers, babies, and fetuses” (13). Meanwhile, within conservative politics more broadly, the rights of the unborn were likewise moving to the center of concern. Writing recently in Politico, Dartmouth’s Randall Balmer has stressed the role race played in this political restructuring. Having lost the moral high ground in the contest over segregation, social conservatives and evangelicals sought to reclaim it on the issue of abortion. In Radiation Nation, Zaretsky provides an ecological inflection to this more familiar story.

Some bodies were more vulnerable than others. Mothers, pregnant women, and children were the first advised to evacuate. In abstract terms, they represented what was most in peril–a society’s ability to reproduce itself. The symbols adopted by the movement came to reflect this. Biotic nationalism was “shot through with ecologically derived images of the vulnerable bodies of mothers, babies, and fetuses” (13). Meanwhile, within conservative politics more broadly, the rights of the unborn were likewise moving to the center of concern. Writing recently in Politico, Dartmouth’s Randall Balmer has stressed the role race played in this political restructuring. Having lost the moral high ground in the contest over segregation, social conservatives and evangelicals sought to reclaim it on the issue of abortion. In Radiation Nation, Zaretsky provides an ecological inflection to this more familiar story.

Zaretsky’s book tells us something about environmental fear politically. At this blog, I’ve written about Sarah J. Ray’s research into student distress over the climate crisis. All this helps. Still, I want to cast a wider net.

At first, “Air can hurt you, too,” seems a neurotic claim. It fits the twitchy, hyper-literal persona David Byrne had established with the group’s first two records. The song is less a warning about air than it is a warning about fear. Its underlying message–its wider inference in the Byrne program–is to push past fear and to embrace life’s wonderful messiness. The theme would become more direct in subsequent records. But the song’s conceit only works if the claims made about air are perceived as paranoid, which they aren’t, by any means. Air can hurt us. Millions die from dirty air every year around the globe, most especially in the global south, where our fossil-fuel-based economics tends to shunt its externalities. Would the song make sense at all in a place where people don surgical masks to go out of doors? These considerations push the song even further away from an environmentalist reading. Or we might put it this way: “Air” functions in a space of relative privilege.

At first, “Air can hurt you, too,” seems a neurotic claim. It fits the twitchy, hyper-literal persona David Byrne had established with the group’s first two records. The song is less a warning about air than it is a warning about fear. Its underlying message–its wider inference in the Byrne program–is to push past fear and to embrace life’s wonderful messiness. The theme would become more direct in subsequent records. But the song’s conceit only works if the claims made about air are perceived as paranoid, which they aren’t, by any means. Air can hurt us. Millions die from dirty air every year around the globe, most especially in the global south, where our fossil-fuel-based economics tends to shunt its externalities. Would the song make sense at all in a place where people don surgical masks to go out of doors? These considerations push the song even further away from an environmentalist reading. Or we might put it this way: “Air” functions in a space of relative privilege.

But air isn’t supposed to hurt any of us, is it? In a 1966 letter to the radical psychiatrist R. D. Laing, Gregory Bateson remarked on how human bodies had evolved according to this supposition. Unlike whales and dolphins, whose blowholes were figured according to the premise–the truth, one might say–that air was only intermittently available, human bodies were formed according to the premise that air was healthful, abundant, and available at all times, right there in front of our faces. “Modern environments” were challenging that “built-in” truth, Bateson noted. This challenge was a cause of “disturbance” in “an epoch … more deeply disturbed than any other in the history of man.”

The social disturbances of the Sixties are well-known. Bateson’s point was to urge Laing to perceive physiological, psychological, social, and environmental disturbance as formally similar phenomena. At the very least, he hoped that a kind of humility might arise from this perception—humility as to human options for dealing with disturbance. His position was that the default option was the source of a good deal of the disturbance. The default option was the drive for mastery, the epistemology of control.

“Control kills, connection heals, come home or die.” This is the written message left by the militant environmentalists in Richard Powers’ 2019 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Overstory, whenever they stage an action. The militancy isn’t Batesonian. The written message is.

Oh, where am I going with this? There’s a thread here I’m unable to grasp between my fingers. Past truths are no longer applicable, yet we still have emotional stakes in them, and in some cases, those stakes are built-in. The species of denial are manifold and respect no particular politics. They trap us into repetitive behaviors that only speed us toward the next “accident.” I began with the idea of environmental fear being under-explored, under-theorized. Bateson’s thought offers ways to think about living systems when trust deteriorates and people are afraid.

0