Editor's Note

This is the first installment of a two-part guest post by Elizabeth Ketelle. Elizabeth Ketelle was a public school teacher and school librarian for thirty-seven years. She has an undergraduate degree in English from San Francisco State University. Upon retirement in 2014, she earned her Master’s Degree in English from Sacramento State University, which she added to the Master’s Degree in Library Science that she earned in 1979 at UC Berkeley. Chosen for the 2006 USA Today National Teacher Team, Elizabeth has taught students from 5th through 12th grades during the course of her career. She is a lifelong reader, writer, teacher, and learner. She is also the best teacher S-USIH blogger, Robin Marie, ever had.

“You don’t remember the Wobblies. You were too young. Or else not even born yet. There never has been anything like them, before or since,” home-spun hero, philosopher, and Army private Jack Malloy passionately asserts in James Jones’ 1951 novel From Here to Eternity

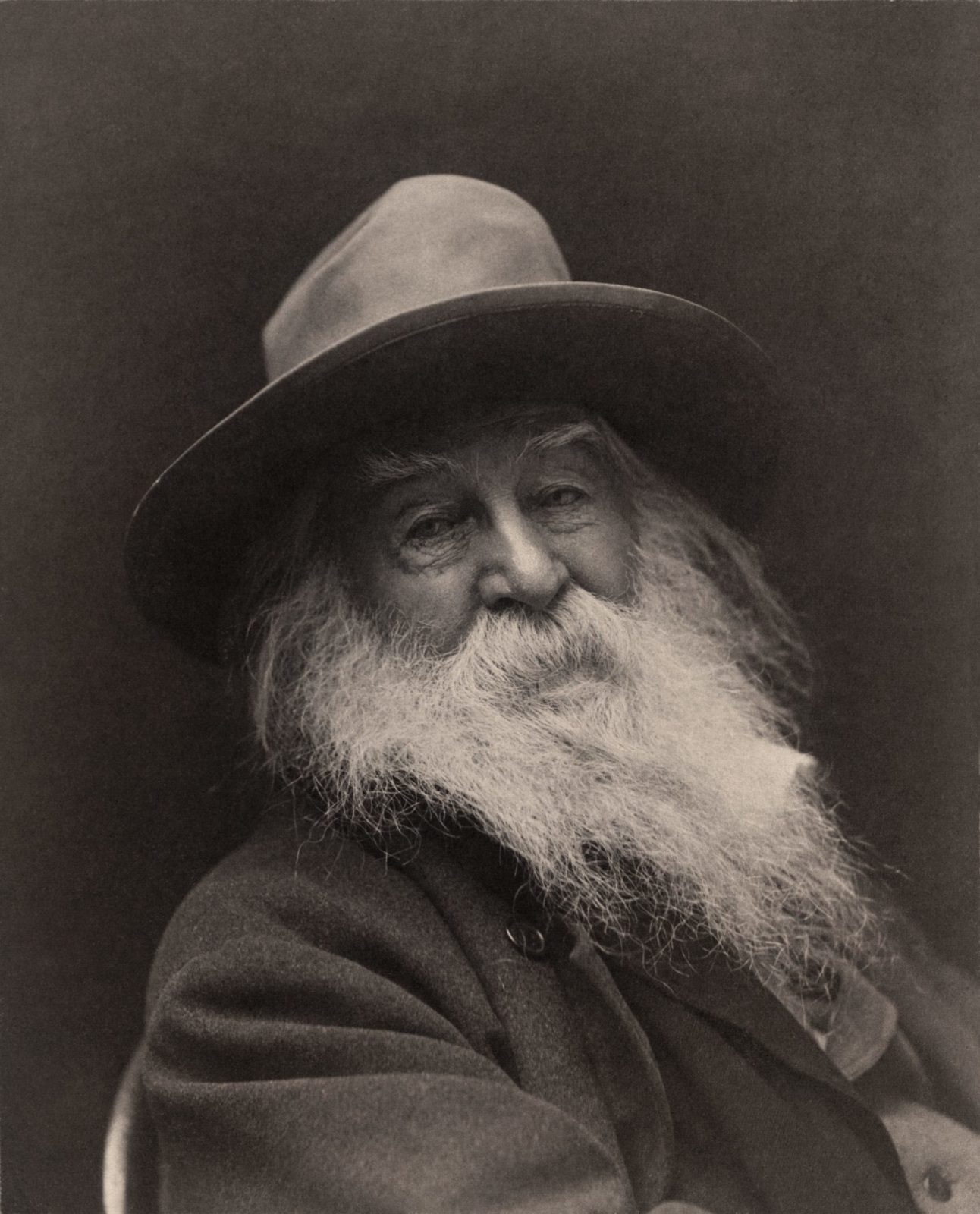

. “. . . They were workstiffs and bindlebums like you and me, but they were welded together by a vision we don’t possess. It was their vision that made them great.” Jones’ explication of the radical labor politics shared by Malloy and the Industrial Workers of the World (or Wobblies) ends with the observation that the “first book [Malloy] bought for himself, with the first money from his first job, was Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass” (635). An undereducated and friendless vagabond, Malloy understands instinctively that Walt Whitman’s poetry and philosophy permeates the Wobbly world view. How these two visions became entwined is one of the most fascinating stories of early 20th century left wing American politics.

My Master’s thesis connects the discourses of socialism, anarchism, humanism, and freethought in early twentieth century America through a study of the ways in which Walt Whitman’s texts helped to shape those forces while the texts themselves were re-shaped in the dynamic interplay, specifically in the formation of the Industrial Workers of the World (or Wobblies).

The process by which 19th century British socialists appropriated Whitman’s poetry as their own is a study in irony, for Whitman’s uniquely American poetry originally found its first avid audience not in America but in Great Britain. It was in his belief in the dawn of an era of true liberty, justice, and democracy that Whitman had great appeal to the anti-monarchy, socialist sentiment fomenting in Europe during his lifetime (1819-1892). In the late nineteenth century, Whitman’s poetry, with its radically subversive language, espousal of comradeship across class lines, and advocacy of utopian democracy, caught the attention of the British Ethical Socialists, a movement that defined socialism in spiritual rather than economic terms, leading its members to espouse an international brotherhood of awakened souls. Attracted to Whitman’s themes of the nobility of the strivings of the common man and his celebration of community, the Ethical Socialist movement took up Whitman’s banner and transferred his vision from America to Great Britain. Whitman’s use of terms like “ensemble,” “en-masse,” “rapport,” “sympathy,” “comrade,” and “solidarity” in his poetry captured the spirit with which the socialist movement was imbued, establishing memes that took on a life of their own. While Whitman fought his entire life against being labeled a socialist (he disliked labels of any kind), his celebration of the indomitable spirit of what he called in his 1872 Preface “an aggregated, inseparable, unprecedented, electric Democratic Nationality” became a meme that found its way to Europe and mutated into a call for social revolution.

A second wave of enthusiastic British readers, however, were more inclined to believe that they had discovered through his poetry a new religion based on male comradeship. One of his first British adherents was John Addington Symonds, a well-known Victorian intellectual. First exposed to Whitman’s poetry in 1865, Symonds became a confirmed Whitmanite whose primary attraction to Leaves of Grass

was his interest in the advocacy for same-sex love apparent in the Calamus poems. This interest eventually turned into a more all-encompassing vision of a general brotherhood of man. Through the influence of Symonds and others in his circle, Whitman’s poetry was widely disseminated among the intelligentsia, promoting familiarity with his memes of comradeship and democratic harmony.

The young, male membership of the Eagle Street College, founded by J.W. Wallace in 1887, was attracted to Whitman’s affirmation of same-sex comradeship but also went beyond that attraction, elevating Whitman to a Christ figure and Whitmanism to the status of a religion. The Ethical Socialist Movement considered his poetry to be a gospel that needed to be spread worldwide, embracing his literature to further their political ends. Through the efforts of all of these ardent admirers, Whitman’s democratic memes found popularity in the socialist community. Through an interlocking system of friendships and shared values, in the late nineteenth century this socialist reading of Whitman’s poetry then crossed back over the Atlantic Ocean and became firmly entrenched in America, eventually positioning Walt Whitman as the centerpiece of socialism there, as well.

In 1883, Whitman took on Horace Traubel as his literary secretary and confidant. Traubel was drawn to the Ethical Culture movement that was established by a reform-minded Jewish rabbi in New York City in the mid-1870s and that strongly echoed the beliefs of the British Ethical Socialists in its liberal humanism. Traubel founded his own magazine – The Conservator – in 1890, intending to propagate this new religious movement, as well as his eclectic political beliefs. Like the journals of the British Ethical Socialist movement, The Conservator became a vehicle for the dissemination of Walt Whitman’s poetry and philosophy. Further, just as the men of the Eagle College found in Walt Whitman’s death (in 1892) the opportunity to spread his message via the British Ethical Socialist movement, Traubel was moved to establish the Walt Whitman Fellowship: International to perpetuate and celebrate Whitman’s legacy after his death. Though Whitman rebelled against this characterization, Traubel repeatedly presented him as a socialist in The Conservator

. Traubel used his magazine to propagate The Whitman Fellowship: International, whose membership eventually included Helen Keller, Robert Ingersoll (“The Great Agnostic”), Jack London, Eugene V. Debs (labor leader and Socialist Party candidate for President), Clarence Darrow (defense attorney), Emma Goldman (anarchist leader), Jane Addams (founder of Chicago’s Hull House), Havelock Ellis (sexologist), and Charlotte Perkins Gilman (feminist author). Thus, through his magazine and his influence, Traubel exposed an entire free-thinking, left-leaning segment of American culture to Walt Whitman.

In a logical extension of this popularity, Whitman come to be associated with the labor movement of early twentieth century America. In the 1871 work Democratic Vistas, his critique of the failings of the American democratic experiment that he saw around him, Whitman addresses the labor question in a footnote to his main text, stating his concern with “The immense problem of the relation, adjustment, conflict, between Labor and its status and pay, on the one side, and the Capital of employers on the other side – looming up over These States like an ominous, limitless, murky cloud, perhaps before long to overshadow us all.” He cites “the increasing aggregation of capital in the hands of a few” that has led to innumerable social ills that ultimately “stand as huge impedimenta of America’s progress.” He offers no solution to this problem, however, except the overall push toward “a sublime and serious Religious Democracy sternly taking command, dissolving the old, sloughing off surfaces, and from its own interior and vital principles, entirely reconstructing Society.” In spite of his ambivalence about the labor question in his prose, Whitman certainly had the ability to celebrate the worker in his poetry in a way that resonated with the laboring class.

When his work was adopted by the radical left, Walt Whitman became a socialist, whether he ever wanted to be one or not. As participants in the socialist, freethought, and anarchist movements, Robert Ingersoll, Clarence Darrow, Eugene V. Debs, and Emma Goldman used Walt Whitman’s democratic, communitarian language and imagery to link their revolutionary rhetoric to traditional American ideals in the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World.

Robert Ingersoll cultivated Freethinker Whitman memes. Ingersoll was a personal friend of Whitman’s. While Whitman was not an atheist, he did share Ingersoll’s fascination with modern science and rejection of formal religious dogma, two issues that resonated with the Freethought community. In spite of the fact that Whitman did not think theological issues were worth debating and preferred a kind of pantheistic, all-encompassing view of the cosmos, Ingersoll reeled him into the Freethought camp. In his eulogy at Whitman’s funeral in 1892, Ingersoll planted Whitman firmly in the Freethinker sphere as the ultimate questioner of authority, beyond dogma, beyond creeds, beyond the boundaries set up by authority, a lover of all mankind. These concepts would resonate in the formation of the IWW.

Clarence Darrow was responsible for creating humanist Whitman memes. Darrow’s exposure to the deep well of human suffering through his courtroom work in labor union cases (in defending clients such Eugene V. Debs, William Haywood, and the McNamara brothers) cultivated in him humanist impulses that folded together the exercise of rationality and compassion, the rejection of the supernatural, and the embrace of science, as well as strong streaks of anarchism and freethought – all elements that resonated with Whitman’s philosophy. Darrow admired Whitman’s vision of the brotherhood of man, his deep compassion for human frailty and flaws, and his vision of an anarchic future in which all can pursue individual happiness. Darrow’s position as a hero and defender of the American working class gave him the influence and opportunity to spread these memes, memes that were eagerly absorbed by the labor union movement, especially the IWW.

Emma Goldman (whose nickname was Red Emma) cultivated anarchist Whitman memes. A darling of the left-wing lecture circuit, Goldman spoke not just on anarchism but on the ways in which drama, literature, and women’s rights interfaced with anarchism. Goldman’s brand of anarchism found a sympathetic vibration in Whitman’s philosophical stance on freedom, especially the idea that the arts are the ultimate form of rebellion against authority. She read Whitman as a heroic anarchist whose mission was to lead the people to a kind of promised land. Goldman used Whitman selectively, but her anarchism resonated deeply with Whitman’s belief that a satisfactory society can only be built by a group of individuals secure enough in their own personal freedom to cooperate voluntarily in a mutual enterprise.

Eugene V. Debs created Christian Socialist Whitman memes. In the early 1890s Debs began reading Whitman and Ingersoll, and by 1898 Debs was able to use his influence to help found the Social Democratic Party. One of the most popular orators in America, in his speeches, Debs was probably the most enthusiastic Whitman proponent in leftwing politics, rejecting very few of Whitman’s core principles and embellishing many. Debs’ success was partly attributable to the fact that he produced a secular co-opting of religious themes, allowing American workers to transfer their disappointed religious fervor to social issues. Transferring Whitman’s ideas of universal brotherhood to the Railroad Brotherhood, Debs preached a gospel of love of the common laborer. Over and over again Debs associated Whitman with Christlike love, joy, and transcendence, creating a sentimental attachment between Whitman and the socialists.

In the next installment, Ketelle explores how the International Workers of the World incorporated and transformed Whitman’s work.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thank you for this interesting post on the various uses/adaptations of Whitman. It’s great to have you with us. Thanks too for refusing the temptation for puns about Whitman containing “multitudes,” which no doubt lurks in territory like this. (Every time I think about him or read him, I have to partly drive that line out of my head, a sort of doomed attempt to cleanse myself.)

Related to my problem, I’m struck by the use of the word “meme” here. That’s a specific word for a kind of cultural transmission, so I’m curious why that word and not words like “idea” or “concept” or “theme” and the like for what you mean to express. I suspect it’s there for specific purposes, so I’m curious about how/why you settled in on that term.

Thanks for your comment. If I may be so bold, I will quote from my thesis on the topic of the meme:

In his book The Selfish Gene, scientist Richard Dawkins has posited the concept

of the “meme” – “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” which

“propagate[s] [itself] in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain” (192).

Geneticist Jacques Monod proposes that like genes, ideas can “fuse, recombine,

segregate their content, [and] evolve” (qtd. in Gleick). Writing in Smithsonian

Magazine, James Gleick notes that memes can take the form of ideas, tunes,

catchphrases, and images, and that rhyme and rhythm are especially helpful in

ingraining memes into human consciousness. Whitman’s poetic interpretation of

democracy was so compelling that his memes took on what Gleick calls “staying

power,” jumping across class and cultural divides to implant themselves in the fabric of

socialism.

Hope this clarifies the issue.

Yep. It does and thank you. So my “I am large. I contain multitudes” is a meme in this sense too. So it follows that within certain varieties of socialism, Whitman’s memes became socialist memes, the homegrown, organic quality of it, presumably different from orthodox Marxism, that being outside. I recall reading Debs, who admired Whitman, and thinking of the ways it was less Marx than a kind of homespun socialism from Terre Haute. Whitman memes inscribed upon his ever-evolving consciousness. I can’t wait to see how it goes down with the Wobblies. Really cool stuff. Thank you.

Elizabeth: Thanks for bringing this to the S-USIH Blog. Fantastic. Huge Whitman fan here.

Love the transnational nature of this study—of Whitman going abroad to be reworked before returning home, in a more radicalized form. It reminds me of Emerson going abroad in Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen’s work, returning home through Nietzsche enthusiasts.

On Whitman not wanting to be known as a socialist, well, he was in good company with Marx. Socialism hadn’t become then what it would be later with Debs, etc. I wonder how Whitman weaves his way into the Black Intellectual Tradition? Which black thinkers appreciated Whitman the most?

S-USIH friend and AAIHS founder Chris Cameron might have something to say about your work, given the appearance of Ingersoll and freethinkers. – TL

Tim,

I’ve never run across Marx saying he didn’t want to be known as a socialist, or more precisely a revolutionary socialist. He attacked “utopian” socialism, “vulgar” socialism, and Lassalle’s brand of socialism (in _Critique of the Gotha Program_), but I don’t think he disclaimed the “socialist” label itself. He did apparently (or supposedly) say “I am not a Marxist,” but that’s a bit different and the context may be important (though perhaps I once knew the exact context for that remark, I no longer do).

p.s. Good stuff on Whitman; thanks to E. Ketelle.

Louis: I confess I made this observation off the cuff, from memory. – TL

Thanks for this. It increased my knowledge about our history. I always wonder if we will have another labor/socialist movement.