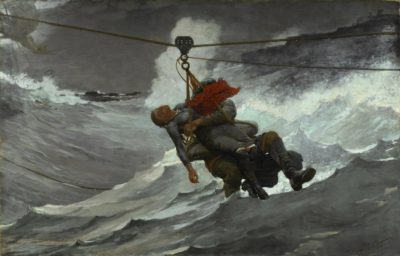

Winslow Homer, “The Life Line” (1884), Philadelphia Museum of Art

As barnyard thefts went, it was a pretty bad one: a fat turkey and fourteen chickens gone, just as the winter of 1828 froze up Washington waterways and holiday feasts beckoned. The culprits behind the heist, as the courts determined, were James Sims and Benjamin Thompson. They might be wayward young men largely lost to history, but their lawyers’ words were not. The defendants’ counselors argued that “they are boys, that the crime for which it is stated that they were guilty of would never have been done had they been in their proper senses.” A pretty juvenile crime by a pair of penitent youths parked in jail: Our story might have stopped there. But, anxious to clear their records, the two boys petitioned all the way to the top of the pardon pile on the president’s desk.

Like most presidents, John Quincy Adams spent years wading through similar pleas. Some letters came from American sailors accused of mutiny or smuggling. Other petitioners (and especially the alleged pirates) claimed they could not pay the court costs. That made navigating the justice system difficult as their appeals wore on. Many petitioners rounded out their official documentation with detailed character statements supplied by pastors, friends, or colleagues. In his neat hand, Adams answered, often with the standard-issue line, “Let the prisoner be discharged…” In a longer formal reply, which he drafted for a clerk to copy, the president expanded on why he believed a pardon was the best path forward.

When it came to Sims’ and Thompson’s case, the fiftysomething Adams mulled the matter for a bit. A father of three unruly sons, Adams finally chose to show leniency. Resting on traditions of jurisprudence, he credited the community’s role in making his final call. “Let a pardon issue,” he wrote, “in consideration of the recommendation of the Judge and Jurors.” In early American parlance, John Quincy Adams granted a full pardon, enacting what civil and military authorities referred to as “the deed of mercy.” Nine days shy of Christmas, James Sims and Benjamin Thompson walked free and out of the records’ sight.

The moral mysteries of our presidents—and why they pardon—yawn wide and deep. At the National Archives, yards of microfilm spin out the fates of women and men seeking second, third, tenth chances to change. Right now, that historical record consumes me. Rolling through pardons from George Washington to Andrew Johnson, I’m collecting evidence to understand a few questions. How did early Americans measure out justice and mercy? What did we forgive, and why? Knowing how people spoke to power in the early republic and seeing how presidents wielded executive privilege, reveals what they banked on America to be. The president’s running dialogue with the relatively powerless shaped the infant democracy, plea by plea.

Competing visions of what constituted clemency or sin mapped out the nation’s moral borders. With plenty of research to come, I can perceive that justice and mercy were both conflicting and connective forces for presidents and petitioners alike. As I see it, this is a developing story of people exercising power, of the Constitution and crime, against the backdrop of early America’s political formation. Part of my new project is to understand how justice and mercy made the presidency. Washington pardoned a key handful, and Johnson swung wide his powers to include Confederate soldiers. What factors in national thought and culture shaped that shift? To get at that, I need to explore the lives of the petitioners and their networks with equal intellectual depth. Presidential pardons spiked noticeably in antebellum America, revealing a citizenry adapting to (and changing) the evolving legal system. What language and arguments won or lost them a leader’s favor?

We have a rough sense of where they began the quest, referencing an ancient royal prerogative with patchworked history and hope. As for moral roots, St. Anselm and Montesquieu offered Americans a wobbly raft of ideas about how to dole out individual and institutional forms of mercy. Heralding the onset of Victorianism, American religious thinkers, scientists, artists, and critics all took turns rewriting stale ideals of good and evil. Archives yield some shards of that saga. Visible forms of justice like presidential pardons serve up rich legal records to assess. Cultural performances of mercy, like those aloft in Winslow Homer’s brush, unfold another view. For, as Homer and his fellow Americans knew: When pain hunts, art can save. Joining together these sources to tell a new history of justice and mercy is my next adventure. All ideas welcome!

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This sounds like a fantastic project. There are so many vectors: individual presidential inclinations, political messages sent, public perceptions crafted, legal precedents set (or violated), slavery, capitalism, class privilege, etc. I wonder too about signals about pardons to perhaps be given—dangled for favors. I can see the letters around a pardon given or denied as much more important, and revealing, than the action itself. – TL