Editor's Note

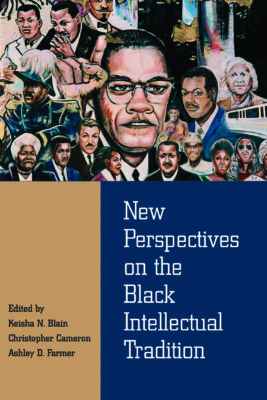

Welcome, readers, to our special roundtable on New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition, edited by Keisha N. Blain, Christopher Cameron, and Ashley D. Farmer (Northwestern University Press, 2018). Please join our conversation in the comments! Thank you. —Sara Georgini

The introduction to this innovative and brilliant volume betrays a bit of frustration with the subfield of intellectual history for continuing to display a gross indifference toward Black scholarship and Black topics. That frustration is amply merited; white intellectual historians are by and large failing to engage this dynamic body of work.

The introduction to this innovative and brilliant volume betrays a bit of frustration with the subfield of intellectual history for continuing to display a gross indifference toward Black scholarship and Black topics. That frustration is amply merited; white intellectual historians are by and large failing to engage this dynamic body of work.

And because we are failing—I am certainly including myself here—I think it’s worth asking what success might look like.

“Engaging this dynamic body of work”—what would that mean? Well, first it would mean acknowledging that we don’t already know it, and that there is a lot to know. It is always wounding to one’s vanity to admit not only that one is ignorant, but that one’s ignorance is so great that it will require a lot of work to rectify. New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition is first and foremost a formidable showcase of exceptionally talented scholars applying themselves to a rich and varied body of texts and traditions, but it is also a quietly forceful demonstration of how vast its subject is. I did not just learn a lot from it: I learned to reappraise how much I did not know.

So that might be the first step of a more successful engagement of white intellectual historians with Black intellectual history: an admission of ignorance and an appreciation of the size of the task in remediating it.

And the second step, therefore, would be actually reading it.

And that in itself presents a problem. Most academics do not have much time to do reading in fields or subfields unrelated to what they are actively teaching or writing, and most white intellectual historians aren’t teaching or writing about a subject that requires

deep reading in Black intellectual history. We may be cognizant enough of the need to include race as one dimension of our analysis to make the addition of a representative Black figure or two logical, but that is a condition which can be dispatched by a rather targeted reading of the scholarship on those particular figures. A more sustained, wide-ranging reading in Black intellectual history is unlikely to occur if that is the standard we are using.

Such a standard generates a self-perpetuating cycle that is hard to break: because white intellectual historians (again, I’m both speaking generally and including myself) haven’t

done enough of the reading, we formulate our courses and our research projects in such a way that we don’t have to do more

.

There is a real problem—in graduate instruction and in the pressures that fall on scholars of all ranks but especially on contingent faculty—in the lack of time available for historians to read widely. Many people who have left academia have testified to how liberating it feels to be able to read non-instrumentally, to read without some larger strategy or without some precise notion of how a book or article will fit into one’s current research project. I certainly do not have a good answer for how to improve that situation. But not being able to solve it doesn’t mean excusing ourselves from making an effort to read as much as we can.

One thing I can think of that might make the problem a little less daunting, however, is this: because historians are trained to read so instrumentally, to read for how we are going to use someone else’s scholarship—even if it’s just sticking it in a footnote—we are always thinking about what we want to say about it. We are always thinking about what it’s missing, where we can “intervene,” or what we can borrow (with attribution) to advance our research. That is, I think, a fairly labor-intensive method of reading, and I’m not sure it’s always necessary. “Engagement” doesn’t have to be so calculating or so controlling.

Much of graduate training and academic habits can instill a kind of knowingness, particularly among people of traditionally privileged groups (white cishet men most of all). That knowingness impedes the kind of humility required not only for admitting ignorance but also for just shutting up and listening—or, in this case, reading. It may be the case that the time is really not there, but for some white scholars, I would imagine that the greater roadblock to a more substantial and sustained engagement with Black intellectual history is precisely this knowingness, this need to make immediate use of what one reads to show that one has already mastered it. And it is precisely what we (people like me) need to check.

So let me begin that checking by saying that New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition

is an excellent place to begin shutting up and reading.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

One answer to your structural question(s) is for there to be more unstructured money in the profession–more for reading and exploring, or updating or even *re*-education. This means grants and leaves for generalized projects. We have lots of specific kinds of grants for research projects, most of which are controlled by criteria and committees that expect specific kinds of products. What if there were more money for reading and thinking and writing that simply went for “vast” generalist “projects.” This money should be inclusive of those in contingent positions. We know that some established tenured profs need to rethink their commitments. They can have some money and leaves too. But 3/4 of the grants I propose should go to contingent faculty and qualified thinkers/researchers (e.g. those with credentials but making money outside of higher ed). These grants could have built-in prods for exploring new areas.

Otherwise, I agree also for the need to be committed to epistemic humility. We need to think harder about what we don’t know, and why. It would be nice if graduate programs, especially those in the humanities, produced those kinds of humble thinkers and learners. But they don’t. The evidence abounds (and yes, they follow a certain identity type). – TL