A few months ago, I got an inquiry from a historian, a PhD and active scholar, but someone whose graduate training had not encompassed the (or a) methodology for intellectual history. This person and I are friends on social media, and so via that channel they sent me a PM with “an intellectual history type question” that they felt I would be helpful in answering. After describing the really fascinating project they want to get started on – and I am sworn to secrecy on what this project is, but I am excited about it – they asked their question: “But how does one even start looking for the history of a CONCEPT? I should know this, but I feel daunted.”

I felt pretty daunted to be the person on the receiving end of this message, and in my head went through all the impostor-syndrome reasons why I was the wrong person to be answering this question. Have I published a single work of peer-reviewed scholarship yet? Have I even finished my book yet? Is there any empirical evidence that I actually know how to do this? But after that all-too-familiar exercise in self-denigration, I said, “I’ll drop you an email.”

Below, edited slightly to protect the confidentiality of my friend’s project, about which they are understandably protective at this early stage, is what I wrote.

Reading it over now, I think it’s pretty solid advice. Feel free to add your own suggestions or corrections in the comments.

__________

Thanks for thinking of me as someone who can help you out on this — I hope your trust is well-placed!

I think there are a number of ways to approach this project, and, more generally, a number of ways that those in our subfield approach the history of a concept / idea.

There’s a “keyword” approach, which is a good place to begin — where you’re looking at the actual development / deployment of the term. Clearly, you’re aiming at something broader than just the specific uses of that term — you’re aiming, if I understand you, at the whole constellation of ideas that that term has either represented along the way or now has come to represent. And it sounds like you’re also exploring laterally the connectivity of that idea with other metaphorical / collateral uses and contexts. Still, an archival dive that gives you a sense of when and how and in what context this term itself has been used would be one good way in, as you will begin to see shades/variants of meaning just looking at that. So you could try the Early American Newspapers, American Historical Newspapers (readex databases, I believe), or — open source — the Chronicling America archive at the Library of Congress online. Search for the term itself, and see in which contexts it appears most frequently. Then you could start exploring the key writers of the time who had something to say in those contexts.

That’s the other main way that those in our subfield approach something like this — we have a question / topic / constellation of ideas we’re wanting to trace through time, so we go to (quite often) the same broad set of primary sources to see what light they shed on the problem at hand. In other words, there’s sort of an undefined but somewhat predictable list of names / texts we would turn to explore the career of an idea in the explicitly “intellectual” registers of American discourse. For each era, you come up with a list of four or five key thinkers and plumb their writings to see where this concept may show up in their work. So maybe for the Revolutionary era / Early Republic that would be John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Phillis Wheatley, Mercy Otis Warren, etc., and in antebellum America that could be anyone from Charles G. Finney to Harriet Beecher Stowe, and for any project that touches on the Gilded Age / Progressive Era, you always want to check in with Jane Addams, Ida B. Wells, Henry Adams, and William James. Basically, for each era in American history we’ve developed a sort of functional canon of writers whose works we can turn to to get a sense of the temper of their times.

And of course the expectation is that whatever shows up explicitly and systematically argued in the “canonical” thinkers will show up in all other registers of American life as well, from saloon songs to potboiler fiction to conduct manuals, etc. So it always helps to look at, say, G. Stanley Hall and Horatio Alger side by side (to take two random examples).

The kind of project you’re working on is a “history of ideas” or “history of thought” project as opposed to a “social history of intellectuals” project — so you’re chasing the idea wherever it shows up, rather than examining a set of necessarily related texts or thinkers. (On the distinction between “intellectual history” and “the social history of intellectuals,” see Dan Wickberg’s article in Rethinking History.)

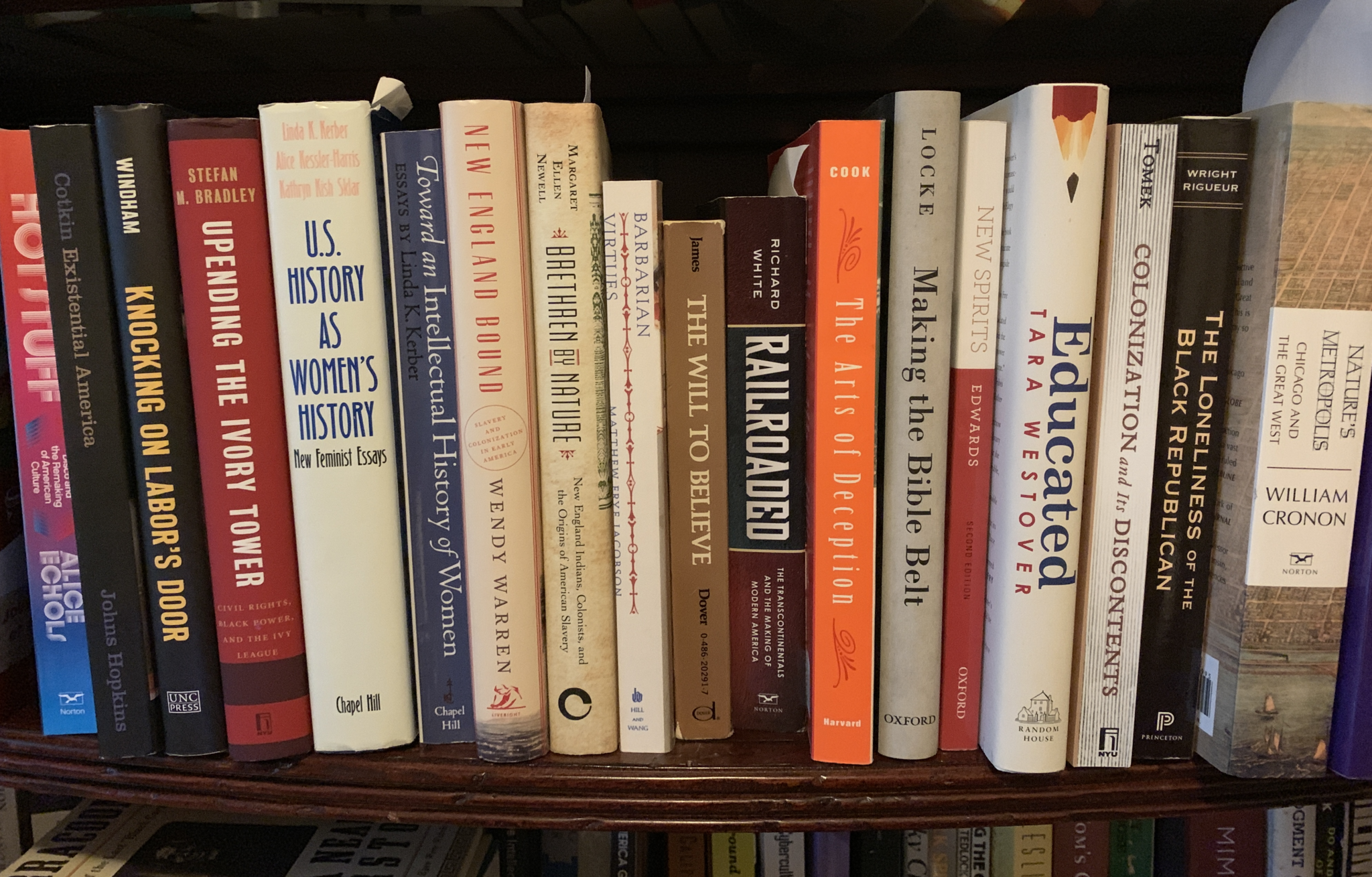

A really good model of this approach would be Sarah E. Igo’s new book on privacy — The Known Citizen: A History of Privacy in Modern America.

Another good model could be Daniel Rodgers’s Age of Fracture,where the idea he’s tracing there is the idea of “the market” as the arbiter of social/cultural values (he’s never very explicit about it, but this is what he’s doing, I think). Rodgers’s introduction to that book talks about how one traces an idea’s path through different kinds of discourses, and could be really helpful. But if you had to pick one, I’d go with Igo, because she’s dealing with the development of a concept andthe development of language about it.

In terms of developing your list of textual sources, you could start with the authors that have been sampled in the Hollinger and Capper primary source reader, but I’d suggest that you go with your gut here and dive into whatever writers / works have seemed to you to have something to say about this concept. Novels, short stories, songs, etc.

I don’t know how helpful this rambling of mine is, but basically I’d suggest this approach:

Read a few outstanding histories of ideas / concepts — Sarah Igo on the notion of privacy, Martha Jones on the idea of birthright citizenship, maybe Susan Pearson on the rise of the notion of “animal rights,” Amy Dru Stanley (outstanding!) From Bondage to Contract, on shifting conceptions / legal status of marriage. And I think you will want to look at historians who work on the boundaries of legal history, gender history, etc — all three of those scholars fit the bill.

Those books could give you some methodological ideas / possibilities and will help you develop some sense of the categories / areas you want to look at. And plunder their bibliographies to help build that list of “emblematic thinkers.”

For each period you’re looking at, start with a generic list of thinkers — the “who’s who” list from the Hollinger and Capper table of contents, or from the index of a major work of intellectual history covering that period — but branch out from there, wherever you find the idea cropping up.

I hope some of this is useful. Don’t listen to impostor syndrome — all history is the history of thought, of the meaning people have made and found in life, and you can tell this part of that story as well as anybody.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Read some theoretical pieces about what a (arguably) concept is.

Koselleck on conceptual history, and, say Hollinger on history of discourses. Classic texts, too, by Skinner and LaCapra. Kerwin Lee Klein’s from History to Theory is good, too.

II have nothing to significant to contribute to the question of just how one goes about investigating/learning of the history of a particular concept, although I too think it helps to acquaint oneself with philosophical treatments of what a concept is as well as appreciate the difference between concept(s) and conception(s), indeed, I would think the history of many concepts is often the history of conceptions of a particular concept. As for the philosophy stuff, there is a helpful entry in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on “concepts.” One might also look at two entries from Larry Solum’s Legal Theory blog: Legal Theory Lexicon 094: Words and Concepts Legal Theory, and Lexicon 028: Concepts and Conceptions. Next, I would suggest reading the brilliant discussion of “basic concepts” and “conceptual schemes” or conceptual frameworks in Michael P. Lynch’s book, Truth in Context: An Essay on Pluralism and Objectivity (MIT Press, 1998). The late philosopher Hilary Putnam speaks to the nature of concepts here and there in his later works in way I’ve found especially illuminating.

I believe it’s also useful to familiarize oneself with the readily available histories of highly contested concepts such as exists on “the self,” rationality, relativism, disease, mental illness, equality, the mind, consciousness, person/personhood, soul/psyche, the “reasonable person” (in legal doctrine) and so forth. On the other hand, some concepts are often presupposed or assumed and rarely critically examined, such as the notion of “sanity,” or one discovers a concept not so much highly contested but used differently depending on the context, such as the notion of “leisure” (sometimes conceptualized as ‘discretionary time’) and, notoriously, the motley meanings of freedom. There is also the fact that conceptual classifications of people, in the social sciences for example, can have what Ian Hacking terms “looping effects,” which means, in brief, their employment, however accurate or true, can serve as self-fulfilling prophecies or (often perniciously) affect how those thereby classified come to view themselves (i.e., they come to think of themselves largely in terms of the conceptual category or classification). Sometimes a theoretical or philosophical analysis or normative treatment of a concept will rely on an historical survey in a manner that is revealing either because it captures more or less the relevant and important meanings of a concept or troubling because it’s a parochial or potted history designed simply to buttress the argument’s premises (see Roy Bhaskar’s Dialectic: The Pulse of Freedom [2008] for an exemplar of the former). Recently I had occasion to examine various conceptions of “fantasy” and “phantasy” (the different spellings referring to different but not unrelated concepts, so it is not simply an affectation) in psychoanalytic theory and praxis (or therapy), which requires a careful reading of literature that can be all too abstract or chock full of technical or obfuscatory jargon, but should not discourage the diligent researcher seeking clarity on such matters. Finally, one may be fairly confident in one’s historical and philosophical grasp of a concept only to come across a novel approach and discussion that reveals the extent of one’s ignorance, as I did upon reading Daniel R. DeNicola’s Understanding Ignorance (MIT Press, 2017).

Not sure how the first sentence got mangled, but please read: I have nothing significant to contribute to….