Editor's Note

This is the fifth in a series of guest posts by Andrew Klumpp, a PhD candidate in American religious history at Southern Methodist University. His research investigates rising rural-urban tensions in the nineteenth-century Midwest, focusing on rural understandings of religious liberty, racial strife, and reform movements. His work has been supported by grants from the State Historical Society of Iowa, the Van Raalte Institute, and the Joint Archives of Holland and has appeared in Methodist History and the 2016 volume The Bible in Political Debate. He also currently serves as the associate general editor of the Historical Series of the Reformed Church in America.

If you spend enough time in small towns, you eventually start to hear each community’s local legends, historical memories passed down through generations, many of which you’d never find in a written history. I’ve heard stories of devastating fires, run-ins with famous politicians or preachers, and on one occasion, a lost Canadian moose taking up residence in a rural community in central Iowa for several weeks. Many of these stories also recount the real or imagined origins of a community as a way to ground a town’s identity in its past. As I’ve started to dig into some of these local legends, I’ve discovered the high stakes world of local rivalries in the nineteenth century and the intentional historical work many communities undertake in order shape memories of local clashes in a way that reflect well on the town.

Undoubtedly, my favorite story of a nineteenth-century local rivalry occurred in a small county in Northwest Iowa when an influx of new Dutch immigrants flooded the county in 1870 and wrestled power away from a small group of the U.S.-born speculators. Today, the Dutch community, Orange City, is known as a thriving, orderly town with a pious population, and the rival settlement, Calliope, once tucked along the banks of the Big Sioux River on the Iowa-South Dakota border, is defunct, scrubbed off the map in the decades following their defeat at the hands of their Dutch neighbors.

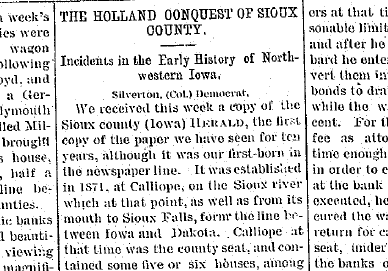

“The Holland Conquest of Sioux County,” The Sioux County Herald, October 5, 1887.

This local rivalry heated up in the fall of 1871, when the Dutch managed to elect three members of the county government, giving them a majority of the county’s officials. Rather than go quietly, their neighbors in Calliope stonewalled the Dutch for months. On the morning of January 23, 1872, the Calliope officials realized the jig was up. A mob of Dutchmen had traveled through the night across the sub-zero, snow-covered prairies to ensure that their representatives took their seats at the county board meeting that was scheduled for that day. The next morning, Dutchmen “arrayed in wood shoes, armed to the teeth, well supplied with spirits… and brimful of wrath and cabbage” descended into the river valley.[1]

Most of the Calliope officials fled across the ice-covered Big Sioux River to the Dakota Territory. When the sheriff insisted that the raiders could only accomplish their goal over his dead body, the mob let him know that unless he surrendered the “dead body he spoke of would not need burying as it would be plugged so full of lead that it would sink like a rock through the fishing hole in the ice of the Big Sioux river.”[2]He promptly surrendered.

Only the county recorder, Rufus Stone, remained. He defiantly declared, “No gang of woodenshoe (sic) Dutchmen can run the county as long as I have anything to do about it.”[3]After the crowd used its wooden shoes to reduce Stone’s front door to kindling, he tried to escape disguised as his wife, complete with her shawl and bonnet. Seeing through the ruse, the Dutchmen chased him back into his home. Stone then asked his wife to create a diversion by providing the Dutchmen with a fake key to the courthouse and safe. Before they could realize that she had duped them, the entire Stone family absconded across the river.[4]

Unable to install their elected officials and locked out of the courthouse, the gang busted down the courthouse doors and commandeered official documents, the county safe and a generous stash of bacon. After loading their spoils onto their sleds, aside from the bacon, which they devoured on the spot, they headed for home, firing warning shots from the top of the ridge to send a message to anyone who might be foolish enough to follow them.[5]The Dutch had proven they were a formidable force and not only at the ballot box. One way or another, they intended to consolidate their power in the county.

A subsequent election transferred the county seat to Orange City and extended the Dutch majority in county government. Within two decades, Calliope disappeared, a forgotten loser in a fierce local battle, and Orange City transformed its image into one of a community defined by order, faith, and fairness. This disappearance of Calliope and the scrubbing clean of Orange City’s legacy were not accidents.

The perspective of the residents of Calliope persisted despite their loss. Writing about the event from his new home in Colorado, the former editor of the Calliope newspaper described the Dutch raid as second in “importance and historical results” only to Peter Stuyvesant’s expulsion of the Swedes from colonial Delaware.[6]One Calliope resident characterized the contraband stolen by the Dutch as “the spoils of war” and suggested that the carnage was a glimpse at what might have happened if Napoleon had ever taken Moscow.[7]Despite their penchant for historical hyperbole, for the residents of Calliope this was not a triumphant transfer of power to honest, upstanding Dutch citizens. It was war.

The Dutch residents did not completely gloss over the events that took place in the lead up to their takeover of the county. Their writings consistently argued that the county’s fortunes dramatically turned around after the Dutch seized power and, invariably, they focused on the Dutch citizens’ victory at the ballot box, which officially transferred the county seat after they commandeered most of the essential documents. The stories the Dutch told and the memories they perpetuated fit the broader narrative they wanted to spread about themselves. Sordid details of their exploits disappeared from their accounts. Instead, their tale recounted upright, Christian people who, as a matter of good governance and Christian duty, took control locally.

The first time I found substantiation of this local legend in newspapers and early histories, I chuckled at the images in these accounts. In part, the humor came from the stark disconnect between wooden-shoe wearing raiders drinking whiskey, stealing bacon, and “brimful of wrath and cabbage,” and the bucolic image the town projects today. Newspapers from the decades following the raid and early local histories demonstrate that the community undertook intentional work to construct its image and downplay this violent incident. The image of the community today, and particularly its history, is the product of that intentional intellectual work. At first blush, it seems like this small town reflects a pastoral rural ideal; however, its history, like many other small towns throughout the Midwest, challenges a simple pastoral ideal of hardscrabble settlers earnestly laboring on the frontier.

_____________

[1]“The Holland Conquest of Sioux County,” The Sioux County Herald

, October 5, 1887. This story originated in the Silverton Democrat

in Silverton, Colorado.

[2]Dyke, 130, 132.

[3]Ibid.,133.

[4]“The Holland Conquest”

[5]Dyke, 134.

[6]“The Holland Conquest.”

[7]Ibid.

0