Editor's Note

After a long hiatus, I have some incomplete thoughts related to a truly interesting and provocative post our own Andy Seal put up months ago about novels and intellectual history. I should add that I also contributed to a conference on the subject of politics and the novel this past fall, hosted by Martin Griffin at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, so some of my thoughts for today come from my contribution there. Thank you to Andy and to Martin.

I’m among those who think intellectual history is an approach more than a subject matter. It’s the study of people thinking or expressing ideas, whoever those people were and wherever they happened to be. But there is some disagreement about this, whether explicit or implicit, when it comes to the books and articles intellectual historians produce. (I should admit that I’ve grown tired of talk about what intellectual history is, so this is my hit-and-run attempt to move on from that discussion.) It stands to reason that the broad approach I describe here—where intellectual history is merely people thinking and expressing thinking—should mean novels and especially novels of and about politics figure among intellectual historians’ primary sources.

This has often been true, especially in the intellectual history of the Southern United States. This partly has to do with sources. There were fewer formal philosophers in those parts in the past, but a few great novelists. It bears reminding that our field, when it came together intentionally as a subfield or approach, roughly around the mid-twentieth century, was very much concerned with novels and literary productions. It ran alongside and often overlapped with the rise of American Studies, and like that field, began with any number of studies trying to figure out things like “the American character” or “myth and symbol” across relatively long periods of time. When, twenty-odd years ago, I told a rather seasoned history professor of mine at Midwestern State in Wichita Falls Texas, that I wanted to do intellectual history, he told me to read Vernon Parrington. I’ve always figured novels were in the field from the start.[1] So this could be a problem of my own (de)formations.

Needless to say, many of the intellectual historians I happen to know teach novels in their classes. Novels present special problems for the study of the past. On its face, anyway, what we in intellectual history do seems different than what literary scholars do, but the more I interact with literary scholars, the harder I find it to distinguish what we do from what they do. Intellectual historians use novels to somehow get at a broader way of thinking specific to time or place. In other words, we tend to be less concerned about how historical context changes existing interpretations of this or that particular novel. The novel or literary work is a historical artifact that opens a window into ways of thinking in a particular place and time and among a group of thinkers.

But these distinctions dissolve pretty quickly. I now wonder whether in practice either group, depending upon interests, actually draw as bright a line as I tended to think between novel-as-historical-artifact and thus window into the past, and window-into-the-past as new way to interpret a novel. By considering the historical context for a novel, we might in the end interpret the novel differently than before, and by starting with an effort to reinterpret a novel, we discover something about its time and place or even another time and place we didn’t know before. Context, after all, is not some passive subject matter historians “pay attention to” but an act and an art of weaving together an archive of sources as we assemble a plausible, truthful narrative about the past. Context is not some inert subject matter waiting to be found in order to better read a novel, nor is a novel some inert historical artifact waiting to have its context better revealed.

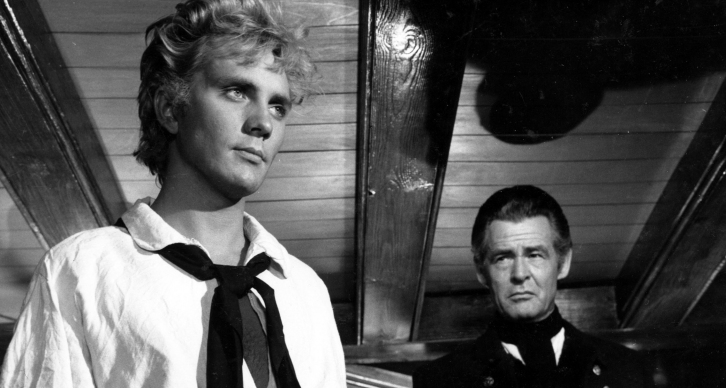

For reasons like these, I’ve always admired the way Hannah Arendt uses novels in her work. She treats them as tools or instruments to better define historically situated political problems and in the process reads them in idiosyncratic ways. In her On Revolution, a comparative intellectual history of the American and French Revolutions with theoretical aims, Melville’s Billy Budd figures centrally. For her, that novel is a story of how innocence cannot have a place in the political realm (Billy in this reading can only be put to death by Vere if the law and with it politics is to persist), which in turn opens up her reading of how innocence or purity leads down the garden path to concerns over necessity in revolutions, the problem of eliminating suffering, which she thinks destroys the political spaces opened by revolutions. Billy Budd helps her explain why the French Revolution turned violent, and how and why revolutions turn violent on the whole. In her Origins of Totalitarianism, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, read as what Edward Said later called “an imperial text,” helps her show how racism developed in South Africa, not the Congo, as she takes Heart of Darkness out of its immediate context. Conrad’s novel is an historical expression of a larger imperial process leading eventually to Totalitarianism. Once racism reaches a level of distilled purity and then collides with the romance of bureaucracy, doing one’s duty can eventually lead down the path of extermination, which is what Totalitarian states did with such terrifying results.

Novels, in this way, enact historical worlds and developments, and historical contexts are enacted in the world of novels, and those perspectives can’t easily be disentangled from one another. Arendt arranges her historical narrative in the deliberative space between those conceptual poles. More precisely, Arendt stakes out a historical and political position precisely by refusing to come down firmly on one side or the other of the illusory disciplinary divide I’ve been describing. Billy Budd reveals something about revolutions, even if Melville wrote about the context of the French Revolution nearly a century after the fact. Heart of Darkness reveals something about Totalitarianism, even if Conrad wrote about Leopold’s Congo, and not about the Boer in South Africa. This is one thing I think intellectual historians might try out when we treat novels. Novels might be good for working out deeper structures or logics of historical events in this way, whatever the specifics of time and place in and around those novels.

Yet, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention how crestfallen or better, confused, I was when, in describing Arendt’s reading of Billy Budd to a group of colleagues, a friend in our English department kindly chided me, saying, “you know, she gets Billy Budd totally wrong.” I have to admit here that I don’t recall my friend’s precise reasoning for why that was, probably because my mind was spinning, thinking about how I needed to get back on the hamster wheel of interpretations to reinterpret the intellectual history I was trying to think about at the time. I wished later on I had asked her if this was so because Arendt didn’t know the various scholarly interpretations of that text. There was no way she could have known about what happened to interpretation of that novel in the years after her own interpretation. (To be fair, I have to think Arendt’s various uses of literature in her work had some relation to friendships she had with Mary McCarthy or Alfred Kazin. She surely tried out her interpretations with them, and they knew about existing interpretations.)

So I’ll conclude my remarks by admitting that I don’t think I have much of a position to tout here so much as a suggestion. I do think some intellectual historians dip a toe into what people are doing in literary and American Studies, and their work is interesting to many of us for that reason. Yet I’d be remiss again if I didn’t admit that Fredrich Nietzsche’s observations in “The Uses and Abuses of History for Life” don’t haunt me at the same time. In that essay, worrying over what he called an “excess of history” in German academic life at the time, by which he really meant an excess of attention to secondary sources—to scholarship—thinkers fell into the trap felt by most moderns, namely that the vast range of interpretations of past events cluttered our minds, making political action seem nigh impossible. Rather than a creative opening to better define a politics or a culture, too much knowledge of that kind made us believe nothing could possibly be new under the sun. But this something anybody in our industry deals with.

So I’m trapped for now, between deciding whether or not a certain ignorance of literary scholarship might actually be a virtue for how intellectual historians interpret the past, and whether intellectual historians need to sharpen their stories by reading more literary scholarship. The plan moving forward is to keep reading novels to open up my historical narratives before dipping a toe in literary scholarship, working to get ever closer to something true.

[1] Yet there is not, and has never been, any fiction in the two volume sourcebook central for teaching surveys in our field, Charles Capper and David Hollinger’s American Intellectual Tradition, now in its 8th edition. There have been literary analyses by figures like Melville (“Hawthorne and His Mosses”) and then later by James Baldwin (“Everybody’s Protest Novel”) and Lionel Trilling (“On the Teaching of Modern Literature”) in its pages, but no short fiction. I can’t imagine how the editors would make that work, for technical reasons having to do with permissions and for reasons of fit. Still, a master of the short story genre would be great to see in the sourcebook. It’s inescapable that we all have our additions and subtractions, however precious. (The blog ran a great series on the sourcebook only recently.)

10 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Good to read you here again, Peter.

Thanks my friend. I hope we can talk novels and music sometime soon. Maybe we can talk about the novel we would write about the feeling of being in novels. So strange being alive nowadays.

The fiction I teach in my classes is conveyed, primarily, through the medium of film. I also talk about the line between fact and fiction, touting some films as creative non-fiction. And, on the history book front, I emphasize the creativity needed to produce readable, compelling non-fiction narrative. On the books-as-novels front, however, I confess to limited engagement. I should do more in that area. I’m probably failing my students by not including at least one per term. I confess, however, to sensitivity about reading loads. So I jealously guard my allotment of non-fiction history books. – TL

Hi Tim. Different strokes for different folks when it comes to this sort of thing. I agree that film is really effective. Some people are better at teaching nonfiction. I’m okay at it, but not as good as at fiction (at least to my mind and a few students’) so I stick with my strengths. Still, I’d love to hear about a sharp guy like you teaching a bit of fiction. Like trying on something different and strange.

Dear Pete,

Just a few quick thoughts about your provocative post. I really like your focus here on the practices of IH (esp. in the classroom) over self-conscious definitions of IH. Personally, one of my ongoing methodological questions remains: how to write intellectual history that makes use of literary sources without treating literary texts as transparent “documents” but rather as rich, complex artifacts of meaning that were sometimes extremely influential in their own time in spheres beyond the literary world?

I am glad to learn that many intellectual historians of your acquaintance make use of fiction in their classrooms. I wonder, though, how widespread this practice is among the IH community at large. After all, as you point out, literature is far less institutionalized in the pedagogical apparatus of IH today (Hollinger and Capper, etc.) than it was at mid-century. My anecdotal survey of conference papers at recent USIH conferences indicates that literary sources are not very popular as a research topic at present (certainly compared to earlier phases of the field).

I would second your point about the historical importance of literature to understanding mid-century culture. In order to make his case for liberalism in _The Vital Center_, Schlesinger feels obliged to cite novelists like Malraux, Silone, and Koestler. Niebuhr or Hofstadter also made glancing allusions to literary works as part of a shared cultural discourse. It’s very hard to imagine an intellectual historian today doing the same. In part, that’s because since the 1950s literature has ceded a great deal of cultural authority to other media formats (film, television, the internet) as a shared medium of public reflection. But that doesn’t mean we should overlook its significance for mid-century. The importance of literature was simply a historical _fact_ of the period. (George Hutchinson’s new book on 1940s cultural history, _Facing the Abyss_, has a first chapter entitled, “When Literature Mattered.”)

At this year’s USIH conference in Chicago, one of the plenary speakers announced from the podium that he “just doesn’t care about poetry” and basically thinks it is irrelevant to historical inquiry. So, I guess my question for you is: if many historians are using fiction in the classroom, why are they keeping this fact hidden? Why do so few anthologies of cutting edge IH work make reference to using literature as a form of historical inquiry? (the recent volume on Modern European IH edited by McMahon and Moyn has nothing about literature, and the Haberski and Hartman’s _American Labyrinth_ has only 1 essay touching on literary matters, I think–about Af-Am writers and secularism)?

It is true that literary scholars and historians both use literature as ways to understand history. But I confess to some misgivings about how this habit works itself out in pedagogical practice. For starters, most sense is that most literary scholars have a much more superficial understanding of the larger historical context in question. Our knowledge of primary sources concerning “World War II” or “The Cold War” is rarely up to par with that of a typical graduate student in history. In my classroom, “the 1950s” usually means a handful of texts (Salinger, Plath, O’Hara, O’Connor, etc.) rather than a survey of events.

We tend to view the past through a pretty small keyhole as it were. This is because literary historians are far more constrained in the materials used to constitute the historical archive. This constraint often tempts us, I fear, to teach rather contorted versions of American history in our classrooms. For example, if you want to know about the cultural norms of the 1920s, there’s no reason you’d need to select a canonical work of literature to illustrate those norms. _The Great Gatsby_, to take an often-used example, is arguably less “representative” of the 1920s than many of the best sellers of its day. Literary quality (rather than historical representativeness) often serves as our main criteria for which texts to discuss. Thus, we end up returning to the same texts again and again and using them as synecdoches for larger historical concerns. For example, in different courses I’ve taught Toni Morrison’s _Beloved_ as illustrative of several different strands of contemporary thought—as offering a “window” into the concerns of postmodernism, 3rd wave feminism, African-American culture, and the post-secular. The book can serve to represent all these things in one way or another; but is this particular text really the best choice to illustrate these variegated themes? Most historians would say “no,” I suspect, and they would do so because they are not constrained by the criteria of aesthetic quality in their selection of sources. But I am: as a professor of English (and lover of the work of Toni Morrison), I can’t comfortably imagine a student taking a course on post-1945 literature without having read _Beloved_. I don’t think that worry troubles many historians.

One more example of how I use literature (in rather questionable ways) to pick up on themes in American cultural history. In a class on American fiction from 1945-1975, I might teach Nabokov’s _Lolita_ as an example of the rise of mass consumerism in the US or Pynchon’s _The Crying of Lot 49 as a text that reflects the themes of the 1960s counter-culture (paranoia and drugs, systems conspiracy, etc.). I bet these choices would seem odd, to say the least, to most historians, who would likely choose sources that “reflect” the culture in more directly tangible ways—say, a selection from William Whyte or David Reisman or a speech by Mario Savio or Tom Hayden. Needless to say, there’s a lot more going on in both these texts (pedophilia, religious allegory) that really have nothing to do with the larger historical concerns of mid-century.

At the end of your essay, you seem to be wrestling with the thorny problem of how to make use of history for present purposes. Nietzsche doesn’t want the weight of history to weigh down our present capacity for action (hence his rebuke to philological or “antiquarian” history). Peter Gordon’s essay “Contextualism and Criticism in the History of Ideas” might prove helpful here. He has some interesting things to say about the perceived dangers of presentism in light of Quentin Skinner’s influential approach for establishing historical contexts). I’ll leave you with two provocative quotations that resonate with your comments on Arendt:

“If we understand a context as a narrowly delimited sphere of meaning that has long ago exhausted its relevance, we will be discouraged from believing that an idea can enjoy the unbounded freedom of movement across time and space, and we will not permit ourselves to imagine that past ideas have any critical significance for the present world.” (p. 47)

“Contextualism need not imply the exhaustion of an idea. On the contrary, when deployed in a more limited way, the recovery of a context that has been neglected or misunderstood may very well facilitate a critical engagement with a given idea and may even help us towards an enhancement of that idea’s possibilities.” (p. 51).

Well more accurately — if we are thinking of the same comment in Chicago — the commenter said they didn’t care about poetry if a historian was producing an analysis of it that claimed it did not really have much to do with power. It wasn’t poetry per se that they weren’t interested in, but analyses that didn’t shed any light on power dynamics.

Hmm, you may well be right. I was referring to a comment made by David Sehat during the Q&A after his talk on legal fundamentalism. I spoke with him briefly in the lobby afterwards, though not about this specific comment on poetry. At the time, it did catch me off guard — it seemed needlessly dismissive of a great and ancient art form! And I seem to remember hearing a few titters around the room — perhaps an indications that others besides myself were surprised at such a baldly public dismissal of poetry (though perhaps just as likely that David gave voice to a position they also held, if silently).

In any case, you seem to have a more vivid memory of this moment than I do, so I’m grateful for the clarification. For what it’s worth, I do diverge from David on this point: I think one can profitably study poetry within analytical frameworks that do not directly address power relations. In fact, I do it all the time! But I can see why, given various methodological and political commitments, some historians would not want to do so. That seems to have been his broader intent — to explain the fundamental premises of his historical practice, as it were, and which discourses are likely to be excluded from that approach.

I’m curious, as I haven’t read your book yet: do you touch on any mid-century novelists in there? There would seem to be many intersections, I’d imagine, between the figures you’ve written on and mid-century novelists sympathetic to certain (racialized) styles of liberalism. I’m thinking in particular of Ralph Ellison, Robert Penn Warren, Saul Bellow, or Flannery O’Connor. I suspect we evaluate that literary/liberal legacy differently, but I would like to know more! Perhaps fodder for a future post.

If I understand right, a fundamental problem here has to do with illuminating context versus aesthetic judgment. Literary folk, presumably, as a tribe, prize aesthetic accomplishment or “quality” while intellectual historians consider whether or not a novel aids broader thinking about particular historical time and place. So a “small keyhole” versus a rather larger swath. I realize this caricatures your position, but I’m doing that to explore problems. My apologies for what follows, because I genuinely appreciate your thoughtful response.

This is difficult, because a book dealing with the broad historical swath between slavery and emancipation, which Beloved concerns, is taught in a post-1945 lit course. So Morrison’s novel deals with that particular context (slavery to freedom) in its pages, but the novel qua novel has its own context, which concerns when it was published, the circumstances of its publication, what it did as a novel in the history of American novels, how that works, and so on. So you’re asking which “history” we’re talking about too, the history of slavery to freedom, or the history of American literature after 1945.

I could be wrong, but I read certain felt burdens on either side in your reading, namely “quality” on the one hand, and “context” as way to “illustrate variegated themes” on the other. My first thought, not surprisingly (probably) is Gordon Hutner’s _What America Read_. There’s a literary historian’s attempt to make, at least partially, some of the case you mean to make. It’s not Fitzgerald or Faulkner that tell us about what people read, but more popular novels. Yet, those dudes do a pretty good job of describing worlds though, eh? Especially Faulkner, but that’s my own thing.

All mean I there is that “quality” has historical context too, as you suggest. How will literature profs teach novels twenty, thirty, one hundred years from now? There’s also some sense of obligation here, which fascinates me. One must teach certain novels for this or that particular course these days. US intellectual historians have the Hollinger/Capper, but I don’t suspect Hollinger or Capper wanted intellectual history surveys to become coercive, where you must teach those volumes, but it has happened in many cases. I’ve never felt bound to teach it so much as that volume is mighty convenient, all in one place. Pragmatists all, in a crude sense, I guess. Let’s see another volume by somebody else, as far as I’m concerned. We can teach without it if we mean to, and I think both those historians would be fascinated to see what we come up with, or at least I hope they would.

You do suggest that literary scholars teach some novel or other for some particular course because its “quality” demands it. Whatever the case, you’re describing are the subtle workings of convention. We can say taste drives literary scholars’ pedagogy while “context” drives intellectual historians’ pedagogy, but that’s really a different kind of taste and convention and aesthetic judgment. That’s all our readings mean. I don’t see much different other than certain industrial proclivities and disciplinary quirks. I was amazed at the last lit conference I was at, to see how much people leaned on more conventional histories of this or that topic.

Really, what do these conventions mean? Not much, to my mind. I’m not sure why we’re so concerned with policing imaginary boundaries.

If someone, somewhere, were to teach Middle Passage, for example, it could involve Morrison’s Beloved, an enactment of the experience, imaginative in profound ways that speaks a kind of truth, as do the documents about the Middle Passage that should necessarily accompany it. Do I teach Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five as a World War II novel or a late 1960s novel? Depends on what you want to work on or teach about. Intellectual history requires a toolkit, so I get your sense of midcentury thinkers there, and I appreciate the uses there in most cases. All I want is a little more of that, a little more acknowledgment that we intellectual historians love to read novels, that they make up the stuff of our minds, that we can bring them to bear in how we see intellectual history. It’s not a revolution, so much as an appeal to our hearts. I just teach what I love so that students will recognize that love and take something from it. It’s not so hard or vexed.

Pete, I love the passion at the end of your post. But let’s keep the police out of it! I’m no more interested than you are in policing boundaries. Where we diverge, I think, is in your suggestion that these boundaries don’t currently exist in practice. Your post and subsequent response suggest that historians and literary scholars basically use the same historical methods in the classroom: “the more I interact with literary scholars, the harder I find it to distinguish what we do from what they do. . . . I now wonder whether in practice either group, depending upon interests, actually draw as bright a line as I tended to think between novel-as-historical-artifact and thus window into the past, and window-into-the-past as new way to interpret a novel.”

This is a claim about current pedagogical practices in our respective academic fields. My post questions some aspects of your characterization of each field. First, I wonder if most intellectual historians do actually use fiction in the classroom as frequently as you suggest. My impression is that they do not—I would love to be wrong about this!—as evidenced, among other places, by the absence of literature in the ubiquitous Hollinger / Capper anthology. My recent experiences at the SUSIH conferences and survey of anthologies of IH as a field of study (e.g. anthologies by McMahon and Moyn, Haberski and Hartman, Whatmore and Young, etc.) bolster this view—they barely feature any discussion of literature at all. Another way to get at this question of current historical practice would be to consult a selection of IH syllabi. If memory serves, the syllabi that LD (or was it Andy?) solicited a few years back on the blog did not feature a lot of literature on them. I could certainly be wrong about this (as an outsider trying to move beyond anecdotal evidence, perhaps I’m consulting the wrong sources), but this is how I’m deriving my picture about the current state of IH practice. Your post suggest that this practice happens in the shadows of the classroom, ‘off the record’ perhaps. It’s an interesting evidentiary problem deserving of historical analysis!

My impression of current classroom practices in literary studies is somewhat different from yours. In my post, I offered some self-descriptions of my own practices in the classroom to characterize how one literary scholar makes rather superficial historical claims in his classroom. I am somewhat ashamed about the way that I teach history through literature! (I’m not proud of this fact, only arguing that it is a fact. I wish literary scholars paid more attention to IH scholarship, which is why I enjoy reading this blog). And since I think my classroom practices are fairly representative of my field, whereas yours seem to depart from the professional norm, I am led to conclude that the kinds of historical methods used by literary scholars are not all that similar to the kinds of methods used by most historians.

Why do I think that literary scholars often use shoddy and unreliable historical methods both in and out of the classroom? One doesn’t have to be a positivist to believe that literary history is a very precarious enterprise for historical understanding: using the “keyhole” of fiction and poetry to understand 20th century history is far more limiting and narrow (discourse-wise) and thus historically unreliable / representative than using the “keyhole” of selections in Capper and Hollinger to do the same. (Dan Wickberg’s essay on the history of sensibilities, among other sources, is very smart on just this point—on the limitations of using a strictly literary source base). I’m clearly more troubled than you are by the “keyhole” approach (a bequest from New Historicism) commonly used in my field—I think it leads literary scholars to get the history somewhat wrong, or at the very least, to make vast unsupported generalizations that typically ratify stale historical clichés. (Just yesterday I trotted out one of these in my class on 20th c. poetry: “The 1950s was an age of conformity and the 1960s was an age of rebellion, as we can see by way of contrast between Richard Wilbur and Allen Ginsberg . . . “)

Whether the methodological boundaries b/t the fields of literature and history should be drawn so starkly – that’s an entirely different question. I suspect we are both interested in blurring those boundaries to some extent. But pretending they don’t exist won’t get us there. Only self-criticism will. I’m troubled by the way most intellectual historians ignore literature when discussing American culture. And I’m troubled by the way most literary history ignores intellectual history when discussing American culture! I’m wholeheartedly with you here: “All I want is a little more of that, a little more acknowledgment that we intellectual historians love to read novels, that they make up the stuff of our minds, that we can bring them to bear in how we see intellectual history.”

How best to “bring them to bear”? Using fiction to understand history is certainly easy and pleasurable . . . in the classroom. Is it also a crucial part of the “toolkit” for writing persuasive intellectual history? Most historians don’t seem as convinced as we are. The next time you see Morrison or Faulkner or Vonnegut or Nabokov cited as an authority in JHI or MIH or JAH or AHR, you let me know!

Fair enough. I understand what you’re getting at here, so yeah, I’ve been on a small mission to change the practices we see in institutional frameworks. I don’t know that I mean to pretend those institutional frameworks don’t exist, only that I think we have lots to learn from one another. This is why I’m loathe to draw the line too brightly, lest our conversations turn into battles over turf, which I think we agree is a bad idea. So yes, I overplay my hand, as you’ve figured out, but it’s not without purpose.

I’m not in the mainstream in my approach I suppose. Really, the hidden, and honestly beautiful thing about US intellectual history is that as a species, intellectual historians I know generally read pretty far and wide. So my cri de coeur is more about what intellectual historians probably read but don’t bring into classrooms quite enough or publish articles with quite enough. I also think again, as a species, intellectual historians are reasonably sophisticated about method, maybe more than other approaches to history, so it pains me a bit to hear about the lack you sense in our institutional frameworks. It could be that, after a season of concern with method, we’ve abandoned such things in recent years. I could be wrong about this.

So I’m confused to be completely honest. I don’t relish a return to more conversations about what intellectual history is, because that can get ponderous in places. I would like, to borrow/paraphrase from a criticism William James had for his genius brother Henry, to have out with it already, just not in the same register. (I teach Henry James so I think William was wrong about Henry when he got impatient with his words, but that happened pretty often.)

This is just a way of saying that I wish we led with problems first and thought more carefully about what we love to read when we approached problems. So in that pragmatic way, we might bring to bear the full toolkit we have at our disposal, our reading lives if not our larger institutional ones.

The model for me in a certain way are African American philosophers, who deploy a tradition to get at problems, so literature, history, formal philosophy, the whole thing. The best course I ever took in my philosophy training in grad school was called “Ralph Ellison: the Literary Artist as Philosopher.” It was chock full of history too. I guess I just want to open up a little and give up the pretense of specialization. I got into intellectual history because I thought it meant I didn’t have to specialize in the traditional sense.

I’ll leave you with this: I’ve never felt more like a historian than I have at literature or philosophy conferences, and I’ve never felt less like a historian than at history conferences. USIH, to mind, at its best, is the exception to that idiosyncratic, experiential rule.