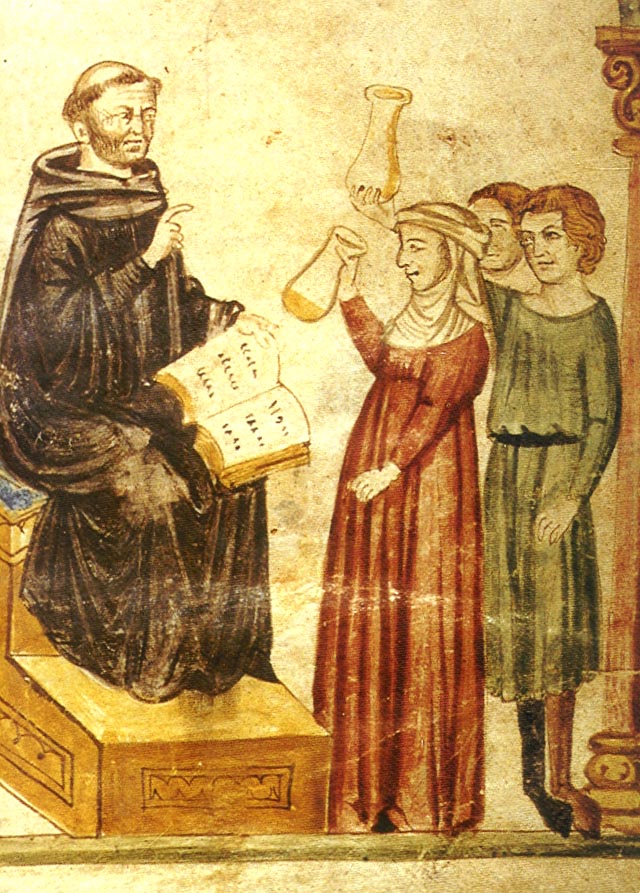

Constantinus Africanus

A while back, I was discussing the history of higher education with a tenured historian of European thought. I was talking about the rise of co-education in the United States in the 19th

century, a history beautifully explored by Andrea Turpin, as one of America’s signal contributions to higher education. My interlocutor made two startling claims in response. First, he claimed that the University of Bologna had been from the beginning a co-educational university. (Sorry, Charlie, but the occasional appearance of an utterly exceptional “woman worthy” in the university’s annals every two or three centuries does not a “co-educational university” make.) Next, he claimed, a propos of literally nothing I had said in our conversation, but probably in response to the look of utter incredulity on my face when he claimed that Bologna had always been a co-ed university, “Western Civilization owes nothing – absolutely nothing– to Africa or to the Arab world. Our heritage is built upon the philosophy of the Greeks, and they were utterly original. The West didn’t borrow its greatness from any outside influences; it didn’t need to.” I guess he is not a big fan of Herodotus.

I thought of that historian recently when I revisited some passages in Rashdall dealing with the primacy of Salerno as a medical school. In the 1936 edition, Rashdall makes this claim: “The origin of the School of Salerno is veiled in impenetrable obscurity” (76). He notes that there are textual traces suggesting that medicine was practiced at Salerno as early as the ninth century, and by the middle of the twelfth century the medical school that existed there was assumed to have ancient origins. But he very quickly dismisses the idea that those origins could in any way be due to the influence of Islamic scholars. “It is no doubt at first sight tempting to trace the medical knowledge and skill of Salerno to contact with the Saracens of Southern Italy or Sicily….The theory which attributes the rise of the School of Salerno to the introduction of Arabic writings by Constantinus Africanus, towards the end of the eleventh century, is a legend of the same order as the legend (to which we shall have to return hereafter) about the discovery of the Roman law at the capture of Amalfi, and is as completely inconsistent with facts and dates as the theory which assumes the northern Renaissance of the eleventh century to begin with the introduction of Arabic translations of Aristotle” (77).

There’s a lot going on here. But simply note one key verbal trick: Rashdall begins by talking about origins (which, he argues, cannot be known), but then shifts to talking about the riseof the school – its emerging prominence as a center of medical knowledge – and asserts emphatically that Islamic scholarship had nothing to do with it. A few paragraphs later, Rashdall doubles down: “the School was in it is origin, and long continued to be, entirely independent of Oriental influences” (80).

The old don doth protest too much, methinks.

And his 1936 editors seemed to think so as well. For, as soon as Rashdall asserts Salerno’s independence of “Oriental influences,” he must contend with the traditions surrounding the well-traveled and well-read Constantinus Africanus, a figure he has already mentioned and whose influence he has already dismissed. Rashdall characterizes this Carthaginian refugee-scholar who became a monk at Monte Cassino as “one of those misty characters in the history of medieval culture whom a reputation for profound knowledge and Oriental travel has surrounded with a halo of half-legendary romance.” Rashdall goes on to tick off a checklist of highlights from C. Africanus’s “legendary” life, though he is not willing to credit the veracity of any of these adventures.

Rashdall’s 1936 editors, though, are less dismissive of Constantinus Africanus as a significant historical figure. Their significant editorial additions / emendations to Rashdall’s work, whether in the body of his text or in the footnotes, are indicated in brackets. And here, where Rashdall introduces the “half-legendary” Africanus, they include a bracketed addition which begins, “There is an extensive literature on Constantinus and his writings: see the note at the end of this chapter…” (80).

The “note” at the conclusion of the chapter was not a simple footnote, but a significant bibliographic intervention. Titled “Additional Note to Chapter III,” the comments, again bracketed to indicate that they are not Rashdall’s, begin as follows: “Recent investigation, notably that of K. Sudhoff, enables us to discuss the early history of Salerno and the significance of Constantinus the African in firmer detail and a better perspective. In the tenth century the four streams of tradition, Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Jewish, which were to combine at Salerno, can be traced…” – and then the note proceeds to trace those traditions as they were reflected in the careers of leading practitioners at Salerno since the 9th

century. The bibliographic mini-essay ends a few hundred words later with the following observation: Although, as Rashdall says, the influence of Salerno…gave way later to that of Montpellier and Bologna, its significance in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries as a centre of Greek and Arabic medicine, of surgery and anatomy, was very great” (85-86).

The sources Rashdall’s editors cited to substantiate and elaborate on that claim were quite extensive. So, the state of the field since 1936 – at least as reflected in the revised edition of the standard historical survey of Europe’s medieval universities – has been that the first great center of medical and scientific knowledge in Europe, the medical school at Salerno, drew from four traditions of knowledge: Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Jewish.

It strikes me that this was a particularly important addition for these scholars to be making in 1936. There were all kinds of claims being made about the greatness of Europe’s cultural heritage, a greatness built upon an imagined ethnic and intellectual purity. In 1936, it was important to acknowledge that “Western civilization,” as symbolized by the medieval university, did not spring fully-formed from the soil of Europe, nor even from the soil of ancient Greece and Rome. If it had “greatness,” it was a greatness forged from the intermingling of diverse intellectual and cultural and religious sources.

That was an important clarification to make in 1936. It is no less important today. And, as long as senior historians like my interlocutor have a hand in the hiring decisions of their institutions, it will continue to be important to emphasize the mutual interdependency and interconnectivity of multiple streams of human thought and experience running through every era, including our own.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I assume your interlocutor must know that parts of the Arab world preserved and built on the work of Aristotle in the years when the Europeans had largely forgotten him (or at least weren’t that interested). The philosopher Al-Farabi is important here. Btw, Strauss (yes, that Strauss) and Cropsey’s History of Political Philosophy has a chapter on Al-Farabi, directly after the one on Augustine and before the one on Maimonides.

Sorry, didn’t close the italics tag properly.

No worries, Louis. I fixed it. To be honest, I decided not to engage further with my interlocutor on the subject. My guess is he would take the “How the Irish Saved Civilization” route and argue that whatever texts the Arabs translated and preserved were first preserved by Irish monks who went to evangelize the Continent. Or something. I don’t know. Honestly, I bet this guy hasn’t read a recent work of peer-reviewed scholarship in his field in twenty years.

I somehow missed, in my first reading of the post, that Rashdall takes a swipe at Arabic translations of Aristotle at the end of that quoted passage. (Wish I had time right now to do a brief research dive into this for my own satisfaction, but I don’t.)

Your earlier post began by noting that Rashdall’s work was originally published in the 1890s. Without knowing anything in detail about Rashdall’s views or hobbyhorses, the last quarter of the 19th century is not a surprising time to find a British (or other Western) academic, esp. one of a certain political persuasion, concerned to minimize “Oriental influences” on “Western civilization” (or on universities in the Middle Ages in particular). So your interlocutor might have been v. comfortable in that era, moreso than in the 21st cent. Just a stray thought…

Louis, it’s funny that you should mention Rashdall’s attention to translations. In the 1895 edition of Vol. 1, which you can read/download in full via google books, he goes on at some length about how Constantinus Africanus is most famous for his translations, including the sayings of Hippocrates, and, just as was the case for the translations of Aristotle that were floating around, the really smart medieval scholars griped about what a crappy translation it was. “As with early versions of Aristotle, the extreme badness of this translation is frequently commented on by the more discerning medieval writers; but though better ones appeared, they long failed to drive out Constantinus” (Rashdall, 1895, I, 81-82).

So again, he has the problem of contending with Constantinus Africanus’s extraordinary reputation and influence, which in his telling endured for centuries, but which was something that deserved / needed to be “driven out.”

His 1936 editors greatly modified this passage, adding several lines of bracketed text in the body of the chapter giving Constantinus his due as a “voluminous translator and writer on medical subjects” and ending with the following statement: “Constantinus was even more important because his translations, through the influence of Salerno, fixed the canon of the are medicinae” (Rashdall 1936, I, 81).

It would be a tedious job to go through this book chapter and verse and compare the significant editorial emendations to the original, and I won’t burden our readers here with such a journey. But it has been valuable for me to look at this “revisionist historiography” and think about the ways that claims of influence, of precedence, of significance in historical writing can reveal as much about the present as they can about the past. And, more particularly for the conflicts I’m looking at, people will throw down over arguments like the one raised in Martin Bernal’s Black Athena not because they are deeply invested “getting the past right” for its own sake but because they are deeply invested in “getting the right past” for the sake of some other “truth” they take to be axiomatic.

Yes. I’ve just been thinking about this very point (“getting the right past”) though in a different context. More on that later, perhaps.

And here we are—where we should be—back at *Black Athena*. This exploration of Rashdall and his editors is excellent background to a retelling of that Bernal’s reception. Oh, how the white university professor changed so little from the 1890s to the 1980s. Many historians and classicists, from that time (late 1980s through the early 2000s) forgot that *Black Athena* didn’t have be 100 percent right to be legitimately plausible. But plausibility is reserved for ensconced white guys, I guess. I wish now I had explored *Black Athena* more in my book, but my story took a different direction. – TL