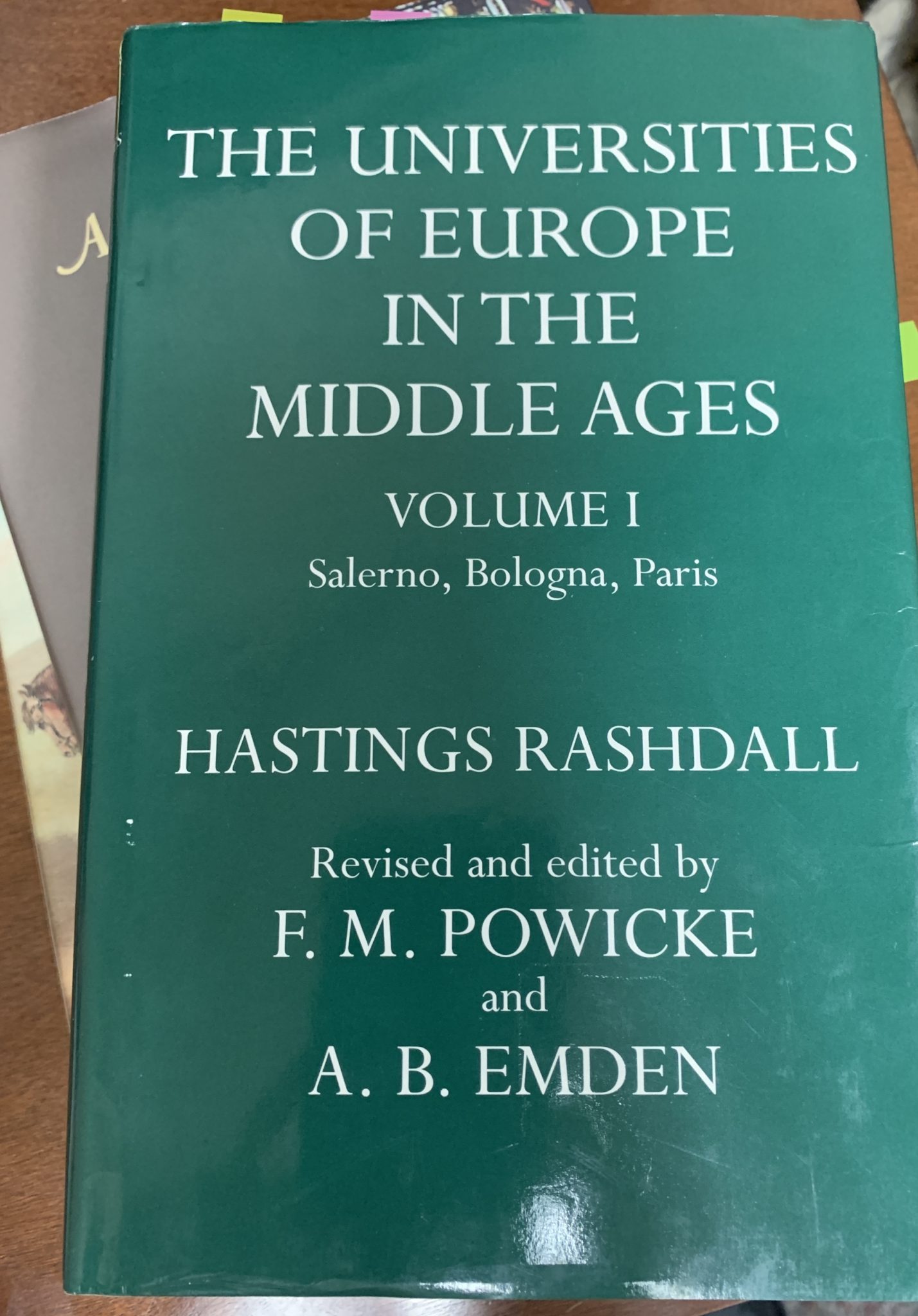

The standard study of the history of the university during the medieval era remains Hastings Rashdall’s monumental text The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages, originally published in the 1890s. Historians of higher education who want to discuss the history of the liberal arts, or the origins of university structure and organization, or long trends and traditions (or the lack thereof) in higher education often resort to Rashdall – and with good reason. Rashdall’s work is magisterial in every sense of the word, a tour de force of painstaking and deep archival research over a sweeping field of inquiry, a cosmic chaos of knowledge presented to the reader by a historian who writes with the absolute assurance of one who has mastered his subject. It is high History with a capital H, and it is essential history – Rashdall’s signal work is still in print today.

The standard study of the history of the university during the medieval era remains Hastings Rashdall’s monumental text The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages, originally published in the 1890s. Historians of higher education who want to discuss the history of the liberal arts, or the origins of university structure and organization, or long trends and traditions (or the lack thereof) in higher education often resort to Rashdall – and with good reason. Rashdall’s work is magisterial in every sense of the word, a tour de force of painstaking and deep archival research over a sweeping field of inquiry, a cosmic chaos of knowledge presented to the reader by a historian who writes with the absolute assurance of one who has mastered his subject. It is high History with a capital H, and it is essential history – Rashdall’s signal work is still in print today.

Well, sort of.

Oxford University Press publishes a revised and updated version of Rashdall’s study, in three volumes. This revision was undertaken after Rashdall’s death by two Oxford historians, F.M. Powicke and A. B. Emden, and was first published in 1936.

In an introduction to their revised edition, the collaborating editor/authors make the following observations:

In addition to the work of coping with the literary output of forty years [that is, the literature on the subject that has appeared since Rashdall’s work was first published], we had to face the perplexities involved in the treatment of Rashdall’s text. His book is not a ‘classic’ like Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empireor Macaulay’s History of England, whose every word and comma must be preserved. Rashdall was a vigorous and often a delightful writer, but he did not possess the infallible composure which is characteristic of a fine or distinictive literary style. Sometimes he wrote hurriedly and carelessly; occasionally he made grammatical slips; and, although he arranged the contents of his book with obvious care, he had little sense of form. He frequently repeated himself or tucked away a significant observation, as it occurred to him, in a place which was not the most relevant to its significance. On the other hand, Rashdall was incapable of writing anything dry or impersonal. He put himself into his books, and he liked to expatiate and to indulge in a genial jibe. He lived in a time, and was trained in a university, in which the study of history was an expression of interest in the ‘humanities,’ and, while it had begun to take account of scientific method, had not yet become professional.

This is a fascinating bit of text, both for what it claims and what it disclaims. Right out of the gate, the collaborating editors deny that Rashdall’s text is too good, much less too great, to be altered. It is not a classic – or, as they have it, a “classic,” in scare-quotes. They do not discuss what the criteria of selection are for determining what makes a work of history a classic, but both examples they cite were popular with a wide readership. Broad familiarity with and approval of those works as written would have rendered ludicrous the prospect of someone rewriting them. Readers came to those works, it is supposed, not simply to read “history” but to read Gibbon and Macaulay on “history.” Less so, it seems, with Rashdall – though apparently the third volume of his work, a deep dive into the founding of Oxford and Cambridge, was widely read.

Immediately after disclaiming classic status for this work, the editors then manage to cast serious doubts on the work’s overall quality as they judge it. The style isn’t fine or distinctive, sometimes the historian wrote in a hurry, his grammar was sketchy, the whole mass of the book is a hot mess of disorderly argumentation, and he buries crucial insights in obscure footnotes. Not exactly a ringing endorsement.

“On the other hand,” the editors continue…

On the other hand, what?

The style isn’t fine, but it’s personal; Rashdall had a distinctive and unmistakable voice, very much his own. He practiced history not as an austere and objective science, but as a humanistic inquiry concerned with morality, with meaning, with ideals and principles.

So, what to do with a historical work that was at that point outdated in some respects, replete with infelicities or even inaccuracies, and so thoroughly characterized by a personal and engaged style of narration that to edit for an “objective” or scientific style would have amounted to having to write the whole book anew?

Here’s how they handled it:

…Rashdall’s text has in general been preserved, but has not been regarded as sacrosanct. We have not hesitated to correct it and to delete erroneous or misleading passages. Here and there, particularly in the first volume, we have substituted new sentences for the old, and, more rarely, we have interpolated new matter. To have called attention to these numerous changes, however trivial or brief, would have been pedantic and might have irritated the reader, but the more significant alterations and additions have been enclosed with square brackets. Similarly, in the footnotes editorial additions and comments have been enclosed in square brackets, but deletions and minor corrections have been made silently.

This strikes me as a rather remarkable and, I would assume, an obsolete approach to the task of revising a major work of scholarship. And make no mistake, Rashdall’s text remains a major work of scholarship – though one wonders if it would or could have remained so without this revision. Part of what makes the history “major” is that it is simply massive in terms of size and scope and sources – a truly monumental text, not so much for its wisdom as simply for its extensive coverage and its evidentiary weight, however mishandled or mismanaged in places. These co-editors – co-authors, in places – recognized what an impossible task it would have been to write a “new” history of the university in Europe in the Middle Ages drawing upon all that Rashdall had to hand plus forty more years of scholarship, but recognized as well that Rashdall’s work had become (if it had not always been) an inadequate and in places a deeply inaccurate account.

So they took it down to the studs, tore out the defective materials, and explained their larger emendations but decided not to bother the reader with “minor” changes, like skilled contractors seeking owner input on major architectural decisions but determining for themselves what would count as major. And, I suppose, that’s what you expect experts to be able to do.

But, more generally, you don’t really expect major works of history to undergo a significant rewrite, even if only in spots, by anyone other than their original authors. If a work of history needs that much rewriting, then it’s time for someone else to look at the materials the author examined as well as whatever other materials may be to hand and write a fresh account of the subject. But to write a “fresh account” that engages anew with any historical problem or question is not the work of an afternoon or a summer or a year. One must commit a significant chunk of one’s life to writing a work of history – several years, maybe even a decade or more. And if the new account didn’t turn out to be that much better or more original or more comprehensive than Rashdall’s narrative, it might seem like valuable time wasted. I mean, Rashdall himself spent twelve years on his history of the medieval university – no wonder he was so unmistakably present within its pages.

Though it’s doubtless the case that the sheer mass of archival sources Rashdall presented in his text all but guaranteed that his work would remain in print simply for the sake of the footnotes, it may also be that the very quirk and “flaw” of Rashdall’s distinctive style gave his work staying power. Perhaps it was precisely because his work was not written in the spirit of history as “science,” because its editors found it so jarring or unreadable in places, that we still find it readable at all.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I can think of a couple of examples of similar posthumous revision in Asian history textbooks, most recently Louis Perez’s revision of Mikiso Hane’s Historical Survey of Japan, or the addition of new authors to World History textbooks after one or more of the original author team becomes unavailable.

Honestly, I kind of wish more works would go through something like this, or that the profession rewarded re-reviewing older classics in light of new scholarship. How well does the old stuff hold up is a question that we should make part of the public discourse more steadily, less fitfully.

Really fascinating post–what an unusual case, and what a deft explanation of the tricky dynamic at play!

I wonder if one of the reasons why this kind of revision is so unusual (beyond intellectual property issues and tenure/promotion considerations) is that the discipline has come to see “revision” itself as a more collective project. It’s not just one text separately being brought up-to-date or tidied up, but instead historians collectively take a new “turn” and try to demonstrate each in their own way how new methods or new focuses of study either surmount or obsolesce older generations of scholarship. “Revisionist” scholarship generally means not emendation but striking out in a totally new direction or rejecting the basic premises of earlier scholars. Perhaps “history from the bottom up” was the first of these more total and collective revisionist projects?

Thanks for the comments. I’m actually mulling all this over in re: the MeToo movement in academe, the relation between scholars and scholarship, and the choices academics have when it comes to dealing with monumental scholarship. Is there ever a case when a field-defining work of history might need a do-over not because of the scholarship per se, but because of the scholar? I’m not at all suggesting that’s what sparked the revision in this case — though I do think that Rashdall’s revisers were dismayed at a stylistic level by how much of the scholar came through in the work. And some of their revisions did amount to taking out objectionable grandstanding/editorializing. (More on that in another post.)

In this particular case, I think Rashdall’s spadework in the archives was just too valuable, because he assembled so many sources in one place, the footnotes are so extensive, there’s so much arcana buried in the footnotes and in the text — and that’s all the underpinnings of the text, which is itself the most thorough English-language account of the founding of the medieval universities of Europe. To write the new Rashdall, or the replacement Rashdall, one would have to somehow encompass all that Rashdall does and then some. It’s probably better in the long run to simply refer to this work than to try to replace it.

Just to echo Andy, this is super fascinating. I can’t think of another similar instance in a work of history (or even non-fiction generally). But, it strikes me that F.M. Powicke and A. B. Emden’s work was/is possibly legitimate. I mean, I want some examples of passages altered, etc., before agreeing overall. I also think, Lora, that you’re right that the subjectivity was what bothered them—in an age of “scientific” history. So I also want examples of what they judged to be “stylistic problems.” I assume there were few to no examples of changes given in the editors’ intro? – TL

Oh certainly their work was legitimate. I will write a future post about this, but most of their substantive emendations/additions — all indicated in brackets in the text — consisted of correcting various assertions that Rashdall made that were less tenable in the light of further scholarship. In the course of some of those emendations, they also “corrected” Rashdall’s ferocious polemics. The significant example I have in mind is Rashdall’s dismissal of the significance of Arabic scholarship in the middle ages, compared to the subsequent editors’ more measured appraisal.

I can think of another multi-volume work that has not been substantially revised but that is continually revisited and remains a significant resource for contemporary historians: Philip Schaff’s 8 volume History of the Christian Church. Schaff also edited the massive English edition of the Ante-Nicene, Nicene, and Post-Nicene Fathers series.

If you read Schaff (which I did with great delight, from the first page of vol. 1 to the last page of vol. 8), you experience a tour de force journey through all the primary and secondary sources available to scholars at the time, and you will not find a better detailed chronology of the development of Christianity, particularly in Western Europe, from the first century to the Enlightenment. But you also get, for example, a virulent anti-Catholicism that makes Schaff’s text infinitely less valuable than his bibliographic headnotes and footnotes.

Instead of revising Schaff, historians simply revisit him for reference and then just roll their own. But any single volume or even multi-volume survey of the history of Christianity written in the English language is deeply indebted to Schaff’s marshaling of sources and scholarship, whether the authors are even aware of the debt or not. When historians plunder someone’s footnotes for sources, without ever engaging their argument, do they always acknowledge their bibliographic indebtedness? A historian who builds on a work whose author built on Schaff might never be the wiser.

I strongly recommend reading “outdated” magisterial works of history — and not just for the footnotes. Eminences grises from bygone eras are good company. You just don’t want them on your dissertation committee. More about that later/elsewhere.

Thanks! It’s good to know that Powicke and Emden used brackets—left a “paper” trail, if you will. Confession: I’ve never read Schaff. Sounds wonderful, however. I’ve long been a fan of Copleston’s now dated 11-volume history of philosophy series. I’ve tried to read them, but always get sidetracked by a new shiny book (insert meme here). – TL