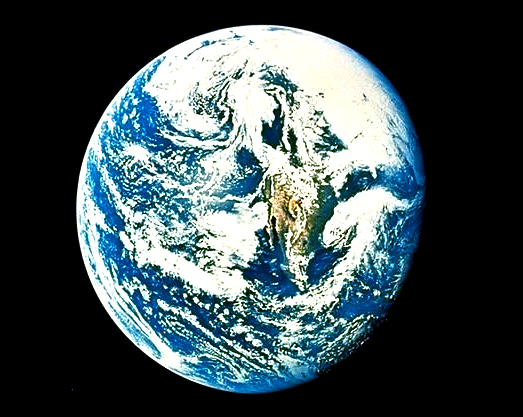

The story, perhaps a legend, goes something like this: a handful of photographs of the earth in space, supplied by the Apollo missions during the nineteen-sixties and early seventies, clarified for humankind the wholeness and lonely fragility of our planet. In an instant, all wars became civil wars, all fights fights between family, and the necessity of caring for our shared environment a shattering revelation.

This view of the rising Earth greeted the Apollo 8 astronauts on December 24, 1968 as they came from behind the Moon after the fourth nearside orbit. The photo is displayed here in its original orientation, though it is more commonly viewed with the lunar surface at the bottom of the photo. Photo credit: NASA

Ritual re-tellings came last December in news articles commemorating the fifty-year anniversary of “Earthrise,” taken by the astronauts on Apollo 8. The photo provided “a unifying expression of vulnerability,” said the story in The Washington Post. The photo became the environmental movement’s icon, the story in The New York Times reported, “a gift of perspective at the end of a dark year.” As iconic as “Earthrise” is “The Blue Marble,” taken by Apollo 17 in 1972, which has been called “the most environmental photograph ever taken.”

The story is often accompanied by some version of this flourish: Isn’t it ironic that these very images that made us newly reverent for the environment came from the space program, which the environmentalists of the time had disparaged? The unspoken message being, of course, good thing we didn’t listen to them! What I’m suggesting here is what if these photos–“Earthrise,” “The Blue Marble,” and their like, as exquisite as they are–didn’t mark change but continuity? What if what is celebrated as new perspective was actually the stubborn persistence of the old?

These questions are among several I took from viewing “Inside,” a recent lecture by Bruno Latour, available on Youtube. An October 2018 article in The New York Times Magazine alerted me to it, a long piece by Ava Kofman about Latour, about his new book, Down To Earth, and about our particular post-truth moment. Latour attributes much of that moment to the fact that we find ourselves disoriented in time and space, due largely to a misleading cosmology. Images of the earth in space are only the most prominent example of an insistence on perceiving ourselves from outside the world. It is as if we’d actually lived Plato’s myth and exited the cave into an ether of pristine abstraction and objectivity. This perception of our home as a globe in space has paralleled our striving for universals in political life and the globalization of the economy.

As an alternative, Latour invites his audience to join him back inside “caveland,” where it’s dark, wet, complex, and confusing. The lecture is a collaboration with some artists and designers whose projected 3-D images surround Latour on the stage as he speaks, sometimes obscuring him completely. Watching and listening, I was reminded of the outdoor installations I saw last year at the AURORA exhibit in downtown Dallas, which I wrote about here on the blog. Latour and his collaborators, like the AURORA artists, seem to begin from the premise that we require radical reorientation to bring perception and experience into sync.

The cave image works as commentary on Western thought, but a cave, enclosed and underground, obscured more by an absence of light than by apparent complexity, isn’t really what Latour offers as an alternative to the image of the globe. Rather, he describes our home as a “critical zone,” a thin layer of sun-energized life atop the compressed remnants of the past. The critical zone consists of “nothing but the activity of the living.” It’s sensitive, fragile, far from equilibrium, and hard to know. Most of all, though, it’s relatively small and thin—”tiny, tiny, tiny,” “a varnish, really”—yet containing “everything we care for, everything we have ever encountered.”

A view of Earth from 36,000 nautical miles away as photographed on May 18, 1969, from the Apollo 10 spacecraft during its trans-lunar journey toward the moon. Photo credit: NASA

The Apollo photos do capture something of this in the earth’s surface glow, a vibrancy indicating organization and life. Seeing this from outside, however, extracts us from it, Latour argues. We can’t represent home and be in it simultaneously. The critical zone is an attempt to overcome this paradox. By inverting the globe, flattening and refolding it “like a tart,” he and his collaborators place us inside a kind of whirlpool, a vortex of processes in the sunshine, some of those processes close and moving quickly, others moving more slowly and thus harder to detect. The systems theorist Gregory Bateson would likely have smiled on this conception of complexly interrelated circuits running transforms of meaning in varying spans of time.

On Christmas Day, 1968, the day after “Earthrise” was first published, poet and writer Archibald MacLeish offered an appreciation which was published on the front page of the Times. His brief column may indeed be the source of the “Earthrise” legend, or in any case, it’s first telling. “Men’s conception of themselves and each other has always depended on their notion of the earth,” he begins. He then employs a history of thought that, while not uncontested, is still in use today. First there was “the medieval notion,” which placed men at the center of the universe. Later there was “the nuclear notion,” which removed them from that center and made them “helpless victims in a senseless farce.” But now, with this photograph, we’d seen earth for the first time “from the depths of space,” “whole and beautiful and round and small.” Perhaps now a new notion of the earth, and of ourselves, was possible, and we could see ourselves “together, brothers on that that bright loveliness in the eternal cold.” Senselessness, might be exchanged for solidarity, presumably, and “man may at last become himself.”

The Blue Marble is a famous photograph of the Earth taken on December 7, 1972, by the crew of the Apollo 17 spacecraft en route to the Moon at a distance of about 29,000 kilometres (18,000 mi). Image Credit: NASA

Although shorn of patriarchal language and modernist despair, Latour’s scheme is formally similar. Instead of “medieval” and “nuclear,” Latour uses the terms “local” and “global.” Whereas MacLeish presents a linear march forward, one notion replacing the one before, Latour recognizes the local and the global as concurrent modes. The West’s current political situation is such that the universals of the global have been discredited and so are being abandoned for the walled-off assurances of the local. Meanwhile the denial of the climate crisis, a crucial intellectual component to this movement, allows the new localists to blame the failures of the global on those outside the walls. Latour’s critical zone is an attempt to “triangulate” the local and global in a different way–a way that faces climate deterioration full on.

The strength of the critical zone as a representation, as Latour himself admits, is that it foregrounds “processes and transformation.” That seems right. As a scholar trained in intellectual history exploring the environmental humanities, I’ve written numerous sentences over the years about the need to reorganize perception, to provide a new account of reality, a new imaginary, etc. So I applaud and admire the efforts of Latour and his collaborators to do just that.

This is especially impressive because I also often wonder, can this actually happen? Can epistemology be rebuilt from the ground up? Can we provide an answer to our current disorientation–an alternative notion, to use MacLeish’s word–that isn’t so strange as to disorient ourselves all the more? At times I wonder if it hasn’t already happened, and that the many attempts at articulation are merely part of the vast apparatus of habit catching up to minds and hearts. Annoying questions! The jury is still out. The jury’s always out–it’s almost never in, come to think of it. I suppose that’s part of what it means to live in the critical zone.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Anthony,

Not long ago I reviewed a book that dealt with this issue: Neil Maher, Apollo in the Age of Aquarius (Reviews in American History, June 2018); while I cannot recommend the book with overall enthusiasm, its section on Whole Earth environmentalism and the public reception of NASA’s “blue marble” photo of earth in 1972 is informative. Citing the same 1968 MacLeish NYT piece that you cite here, Maher notes that indeed the early reaction to earth views from space was to call for peace and brotherhood; eventually NASA began (initially with halfhearted commitment) to incorporate environmental projects into its missions; yet it was not until Earth Day in 1990 that the blue marble image became a widespread symbol of global environmentalism.

Having lived through that entire period, my hunch is that the impact of the earth photos of the late 1960s and the 1970s stemmed from their novelty. They opened a window of opportunity for reconceptualizing the vulnerability of the planet to destructive wars and ecological disasters. Unfortunately the novelty effect ran its course; certain constituencies have definitely altered their views based on the small-isolated-planet imagery (or in some cases the imagery reinforced views they had already adopted); yet other persons or groups soon forgot the message; and, of course, organized push back from ideological or economic agents have helped to close that window of opportunity. More generally, I have no doubt that epistemological re-orientations inspired by such imagery will occur; I would caution, however, that not everyone will embrace or adopt the new perspectives and not all new perspectives will align with each other.

DREW

Thank you for these insights, Drew.

I especially appreciated the good sense in your last sentence: “More generally, I have no doubt that epistemological re-orientations inspired by such imagery will occur; I would caution, however, that not everyone will embrace or adopt the new perspectives and not all new perspectives will align with each other.”

Anthony, this post brings up an issue I’m encountering in my own work now, and I’m so glad you highlighted it. Macleish’s early interpretation of the “Big Blue Marble” has been somewhat uncritically adopted by commentators looking back at this historic moment. Macleish’s impression has become a framing device.

I’m seeing the same thing in the historiography of higher education when it comes to things like the introduction of the elective system, the utilitarian rationale behind the land grants, the professionalization of the professoriate, etc., and how all these have impacted the undergraduate curriculum. Plenty of people at the time saw the move toward multiplicity as a tragedy, a loss, a shattering of “coherence” that once presumably characterized the undergraduate course of study. Words like “chaos,” “disorder,” “disarray,” “confusion,” appear not just in the primary sources, not just in the polemics of higher education administrators/commentators writing during this time, but persist in many historians’ characterizations of the moment. There’s a nostalgia for the good old days, not just in authors of the time who were disaffected with various manifestations of modernity, but in historians who write about them — and it’s not intentional. But it seeps into the language that we use to frame the past.

So my current task is finding all kinds of other words to describe what happened to the undergraduate curriculum that are descriptive but not tinged with disapproval — “multiplicitous,” “pluralizing,” “ramifying,” etc. It isn’t easy, because the default view of the period is “curricular chaos,” but that’s just one perspective among many, just as Macleish’s read of that photo was one perspective among many.

Anyway, thanks for this post.

I’m glad this post sparked some thinking about your own task. If you have the chance, check out the Latour lecture. That’s really where the action is.

It seems on the face of it an odd proposition that “We can’t represent home and be in it simultaneously.” While the status of a representation is always subject to the medium, the context, the craft or aesthetic input, and to an extent the audience, there’s no particular logical conclusion to be drawn that this means we can’t also be in that part of human life thus represented. Even a young kid drawing his or her house is trying to represent something they are actually dwelling in, and is usually capable also of explaining the necessary distinctions.

It should be more a pragmatic assumption that we have, fortunately, representations of our home that we also live in, even if — and I wouldn’t deny this — such representations can seem like a refuge from reality at times, or be misused in ideological conflict. It’s true that the search for universals in politics finds its reflection in the culture-flattening globalization of economics, but the existence of these images is, I’d argue, something valuable: a permanent critique of the kind of zero-sum, tribally exclusive, and narrow-gauge thinking that assumes that some kind of wall between countries, ethnic groups, or religions will solve globally mobile challenges to do with air, water, and human safety.

It may be the case too — I’m not sure — that Latour is opening the door to the nation as another version of the cave, which would not be a bad metaphor for the dangerously nostalgic and self-regarding nationalisms we see growing across the world. The local/global is an attractive alternative dynamic to the tribal campfire, but it has its blind spots. The “local” activist on his way to an organizing conference in Tokyo and the “global” manager on her way to a business meeting in Frankfurt are both likely to be traveling on their US passports and also convinced of their role in valuable international networking.

Yes, it makes sense to intervene on that point. In summarizing Latour, I certainly may have over-simplified his thinking–I hope readers will be inspired to go to the source and check out his lecture, “Inside.” Martin, it’s clear you see what Latour is getting at, and I can’t disagree–or imagine Latour could, either–with your point about the value of representations as critique. The critical zone (I didn’t insert the visual but you can click to it via a link), Latour’s global-as-local/local-as-global triangulation, is a familiar, but not unwelcome, effort to get past an anchored dualism. I read your last sentence as describing something like this in concrete terms.

Anthony — thanks, I now realize that that I didn’t see the link to the actual lecture, which I will watch at the next opportunity. I think my comments were also somewhat diffuse because I wasn’t sure if it was Latour’s or your argument that followed on the quote about representation. Upon rereading the piece, though, I’m struck as I was the first time by the way in which MacLeish used “solidarity” as a key term in his response to the photos. I think that that has something laterally bonding and non-dualistic about it, and in that sense it’s not impossible that MacLeish would have accepted concurrent modes too.