One of the things that keeps historians in business is that as the present changes, we see things in the past that we didn’t see before. Or, to put this a little differently, the present churns up new things in need of explanation. This is especially true of surprising events like Donald Trump’s election. And we’re beginning to see the fruits of post-2016 reorientations of our points of view.

The most recent Journal of American History features a fascinating essay by Joseph Fronczak that explores connections between the American far right in the 1930s and fascist movements around the world.[1] Fronczak, an Associate Research Scholar at Princeton, who is working on a book about global antifascism during the Great Depression, argues that we should understand fascism less as a political ideology and more as a political practice, a kind of politics that he also astutely describes as “participatory antidemocracy,” linking often violent grassroots mobilization against the left with leadership by economic elites. If we understand fascism this way, he suggests, we can see all the ways in which the American far right during the Great Depression drew from and sought connections with fascist movements in other countries.

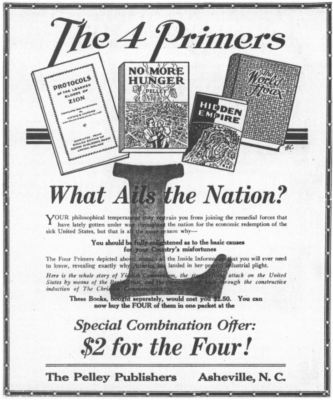

An advertisement for the Silver Shirts that appeared in their founder William Dudley Pelley’s periodical, LIberation, in May 1938. Source.

While some of the movements that Fronczak discusses are often linked by historians to fascism – such as the KKK, the Silver Shirts, the German-American Bund, the Black Legion, and the Wall Street conspirators famously exposed by Smedley Butler – others are not. Most notably, he argues that the Mohawk Valley Formula, a plan for strikebreaking said to be authored by Remington Rand chairman James Rand, Jr, should be understood as essentially fascist. Crucially, he shows that grassroots actors on both sides of the 1930s struggles he discusses frequently identified the anti-labor agitators as “fascist.”

At least two things, Fronczak suggests, have stood in the way of understanding these American fascist movements, their relationship to fascism in other countries, and the relationship of modern American conservatism to them. First, there has long been a sense among historians that America was somehow immune to fascism. Subsequently, the American individuals and movements that Fronczak discusses are not always seen as fascist and, obviously with the notable exception of the German-American Bund, are rarely connected to international fascism. Second, historians of modern American conservatism have tended to start their stories after World War II. The interwar right plays a too minor role in our understandings of late 20th-century and early 21st-century conservatism.[2]

In the conclusion of his JAH piece, Fronczak sketches the connections between what he sees as interwar American fascism and the post-war American right. These connections involve some personnel, but, more crucially, the continuing centrality of “an unstable bond of popular radicalism and high capital [which] has enabled the modern Right to amass power, and yet also has ensured that it remains a volatile political bloc.’”

Since 2016, there has been an ongoing argument, inside and outside the academy, about the appropriateness of characterizing Donald Trump and the political movement behind him as fascist. Among those academics leading the way in suggesting that Trumpism is a species of fascism have been a number of twentieth-century European historians, who have often argued in terms of similarities they perceive between what is happening in the U.S. in the early 21st-century and what happened in Europe in the interwar period. Most prominent among these scholars is the Yale historian Timothy Snyder, whose On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century was an instant best-seller early in 2017. Last year, Snyder published a follow-up to On Tyranny, The Road to Unfreedom, which warns of Russia as the font of authoritarianism in the world today.

As I noted in a post on this blog back in 2017, though I believed (and believe) that Putin is generally a bad actor in the world today and that Russian interference in the 2016 election must be investigated, I don’t think Russia today or Europe in the interwar period provide the best clues to understanding what is going on in American politics today. The deepest roots of Trumpism are American. And any proper understanding of Trump will be grounded, in large measure, in an understanding of American politics and American history.

Sometimes, those who focus on Trump’s American roots have been dismissive of the idea that Trump is a fascist. Precisely because of the general aversion to acknowledging the existence of American fascism, there are versions of the argument that Trump is a fascist that serve to deflect attention away from Trump’s American roots in favor of, e.g., arguments about insidious forces from abroad or universal categories of “extremism.” Calling Trump a fascist can be a way of “othering” him, of positing an America that, left to its own devices, could never produce a Donald Trump. But that kind of exceptionalism is fundamentally false.

One of the values of Fronczak’s essay is that it reminds us that Trump’s rootedness in the political culture of the American right is entirely consonant with his fascism. And that the American right – like the American center and the American left – is best understood in the context of the international circulation of political ideas and practices.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’ve said in the past that FDR should get a lot more credit than he does for keeping the US from going either fascist or communist.

Thanks for this, Ben. I’ve been thinking about this question of Trump and fascism a lot lately and will intervene in it in some format sometime soon, but I think the one point you bring up here is important: for those who seem to want to define fascism very narrowly, appealing to or participating in this emphasis on European fascism as specifically European and European only plays a role, and a dubious one.