Earlier this week, David Brooks wrote a column bemoaning a generation gap that he suggests is tearing apart American society. Channeling Midge Decter – after whose 1975 tract Liberal Parents, Radical Children he named his column – Brooks suggests today’s youth are intolerant extremists who have abandoned “meliorism.” As is typical of Brooks, there’s not much of an argument in the column. It’s largely a series of appeals to conventional wisdom bolstered by pop sociology that is often at odds with simple fact.[1]

Earlier this week, David Brooks wrote a column bemoaning a generation gap that he suggests is tearing apart American society. Channeling Midge Decter – after whose 1975 tract Liberal Parents, Radical Children he named his column – Brooks suggests today’s youth are intolerant extremists who have abandoned “meliorism.” As is typical of Brooks, there’s not much of an argument in the column. It’s largely a series of appeals to conventional wisdom bolstered by pop sociology that is often at odds with simple fact.[1]

But at the heart of this largely rote piece of Brooksian pablum is a claim that deserves a closer look. “The younger militants,” writes Brooks, “tend to have been influenced by the cultural Marxism that is now the lingua franca in the elite academy.” This is interesting both for what Brooks appears to be trying to say and, more immediately, how he has decided to say it.

Readers of this blog are probably familiar with the phrase “Cultural Marxism.” I blogged a bit about its history on a couple occasions back in 2011. That summer, the phrase had been thrust into public consciousness when it featured prominently in the manifesto distributed by the Norwegian far-right terrorist Anders Behring Breivik on the day that he murdered sixty-nine people.

Breivik seems to have gotten the concept from William Lind, an American political operative associated with both the Free Congress Foundation and Lyndon LaRouche’s organizations. Lind’s conception of Cultural Marxism was explicitly anti-Semitic. As Chip Berlet, who investigates far-right organizations, puts it, the theory is that “a small group of Marxist Jews who formed the Frankfurt School set out to destroy Western Culture through a conspiracy to promote multiculturalism and collectivist economic theories.” Lind began promoting these ideas in the late 1980s and continued to do so throughout the 1990s. In 2002, he even presented them to a Holocaust denial conference sponsored by the anti-Semitic Barnes Review.

Over the course of these years, the idea of Cultural Marxism spread across the American far right. It got a big boost from Andrew Breitbart, who adopted the term and wrote extensively about the danger posed by the Frankfurt School in his book Righteous Indignation (2011). Just last year, National Security Council staffer Rich Higgins was fired by then National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster for, among other offenses, including conspiracy theories about Cultural Marxism in a number of memos (like Breivik he saw “political correctness” as one of its insidious effects).

Over the course of these years, the idea of Cultural Marxism spread across the American far right. It got a big boost from Andrew Breitbart, who adopted the term and wrote extensively about the danger posed by the Frankfurt School in his book Righteous Indignation (2011). Just last year, National Security Council staffer Rich Higgins was fired by then National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster for, among other offenses, including conspiracy theories about Cultural Marxism in a number of memos (like Breivik he saw “political correctness” as one of its insidious effects).

Given the genealogy of this term – which, as Samuel Moyn and a number of others have pointed out, also echoes the German Nazi phrase Kulturbolschewismus (“cultural Bolshevism”) – why would a columnist like David Brooks, who is himself Jewish in background (if, perhaps, no longer in faith) and who has tried to build his brand identity by peddling in respectability and civility, adopt the term?

After receiving quite a bit of blowback on social media for his invocation of Cultural Marxism, Brooks went on Twitter yesterday and defended his use of the term. Brooks linked to a piece in the Jewish online journal Tablet by the attorney Alexander Zubatov entitled “Just Because Anti-Semites Talk About ‘Cultural Marxism’ Doesn’t Mean It Isn’t Real,” an article Brooks called “an excellent survey of cultural Marxism. Much more sophisticated than the way the phrase gets thrown around on Twitter.”

Zubatov dismisses the Frankfurt School-related conspiracy theories of folks like Lind (noting that Adorno was a defender of “Western high culture”), only to launch a very similar narrative with a slightly different cast of Marxist characters. For Zubatov, it wasn’t so much the Frankfurt School, but rather György Lukács, Louis Althusser, Herbert Marcuse[2], Edward Said, Judith Butler, Stuart Hall, and, above all, Antonio Gramsci who are at fault. And though this is a more multicultural cast of villains than Lind’s exclusively Jewish antagonists, Zubatov similarly maintains that Cultural Marxism is “a coherent program” and accuses it of many of the same things that Lind does:

It is a short step from the Marxist and cultural Marxist premise that ideas are, at their core, expressions of power to rampant, divisive identity politics and the routine judging of people and their cultural contributions based on their race, gender, sexuality and religion — precisely the kinds of judgments that the high ideals of liberal universalism and the foremost thinkers of the Civil Rights Era thought to be foul plays in the game. And it is a short step from this collection of reductive and simplistic conceptions of the “oppressor” and the “oppressed” to public shaming, forced resignations and all manner of institutional and corporate policy dictated by enraged Twitter mobs, the sexual McCarthyism of #MeToo’s excesses, and the incessant, resounding, comically misdirected and increasingly hollow cries of “racist,” “sexist,” “misogynist,” “homophobe,” “Islamophobe,” “transphobe” and more that have yet to be invented to demonize all those with whom the brittle hordes partaking in such calumnies happen to disagree.

Zubatov prominently cites the English philosopher Russell Blackford in support of his contentions about Cultural Marxism. Blackford does suggest that the phrase “cultural Marxism” predates its use by the American far right and may, in principle, have some utility. But in the very piece Zubatov cites, Blackford concludes that the phrase is so marked by its connection to anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that it is, in practice, largely unusable:

In everyday contexts, those of us who do not accept the narrative of a grand, semi-conspiratorial movement aimed at producing moral degeneracy should probably avoid using the term “cultural Marxism.” . . . Like other controversial expressions with complex histories (“political correctness” is another that comes to mind), “cultural Marxism” is a term that needs careful unpacking.

Of course, Zubatov, much less Brooks, is not very interested in carefully unpacking anything. Zubatov and Brooks are attached to a pejorative which they’d prefer to be uncoupled from the anti-Semitism to which it has been usually attached.

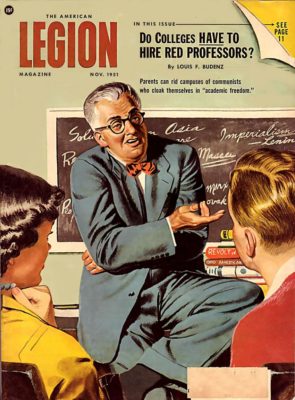

But even beyond the impossibility of removing the anti-Semitic connotations from the notion of Cultural Marxism, the underlying story of Marxists in our universities undermining liberal universalism and leading young Americans astray is nothing more than a lazy right-wing myth that goes back at least as far as the Second Red Scare. If then these tales suggested that professors (and potentially their enthralled students) were a Fifth Column for the Soviet Union in the Cold War, Brooks’s assertion that “cultural Marxism that is now the lingua franca in the elite academy” has slightly different resonances today. Readers are, I think, supposed to be reminded of concerns about the predominance of Democrats among faculty members as well as concerns about the supposed intolerance of the campus left (especially students). Of course, most Democrats (including most Democratic faculty members) are not Marxists. And concerns about student intolerance are wildly misplaced. Actual social science suggests that people have been getting more tolerant, that people on the left are generally more tolerant than people on the right, and that college graduates are more tolerant than those without college degrees.

But even beyond the impossibility of removing the anti-Semitic connotations from the notion of Cultural Marxism, the underlying story of Marxists in our universities undermining liberal universalism and leading young Americans astray is nothing more than a lazy right-wing myth that goes back at least as far as the Second Red Scare. If then these tales suggested that professors (and potentially their enthralled students) were a Fifth Column for the Soviet Union in the Cold War, Brooks’s assertion that “cultural Marxism that is now the lingua franca in the elite academy” has slightly different resonances today. Readers are, I think, supposed to be reminded of concerns about the predominance of Democrats among faculty members as well as concerns about the supposed intolerance of the campus left (especially students). Of course, most Democrats (including most Democratic faculty members) are not Marxists. And concerns about student intolerance are wildly misplaced. Actual social science suggests that people have been getting more tolerant, that people on the left are generally more tolerant than people on the right, and that college graduates are more tolerant than those without college degrees.

“Cultural Marxism” is a toxic expression that entered our national discourse as an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. It ought to be avoided on that basis alone, especially given the more general mainstreaming of anti-Semitism on the American right today. That the attendant critique of the university is itself devoid of merit simply underscores that fact.

Notes

[1] Most of the column concerns the generation gap on the left, but the biggest whopper may be in its aside on the generation gap on the right, which Brooks (correctly) says is between “old Trumpians” and a younger conservatives that has little influence on the GOP. But then things go off the rails: “The boomer conservatives, raised in the era of Reagan, generally believe in universal systems — universal capitalism, universal democracy and the open movement of people and goods. Younger educated conservatives are more likely to see the dream of universal democracy as hopelessly naïve, and the system of global capitalism as a betrayal of the working class.” Boomer conservatives – who are now ages 54-72 – are, in fact, Trump’s base. And they bear little if any resemblance to Brooks’s description of them. They are, for example, the Americans most suspicious of immigration.

[2] Can’t leave the Frankfurt School out entirely, I suppose.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’d be curious if and how my research causes you to reformulate some of your claims above.

Very good post, and I like the allusion (not illusion) conveyed by the last two words of the post’s title, which many readers of this blog will catch, though in my case it was a slightly delayed reaction.

Thanks for this educational post. Re “the underlying story of Marxists in our universities undermining liberal universalism and leading young Americans astray is nothing more than a lazy right-wing myth that goes back at least as far as the Second Red Scare.” If my book ever gets published, I’ll be able to help people see that this story goes back at least to the 1930s when the likes of William Bell Riley, Gerald Winrod, and their allies were tying the Marxist-Jewish conspiracy to evolutionary immoralism (and other “isms”) spreading on college campuses.

Jameson on Jameson: Conversations on Cultural Marxism (Post-Contemporary Interventions)

Duke University Press 2007

Cultural Marxism in Postwar Britain: History, the New Left, and the Origins of Cultural Studies (Post-Contemporary Interventions) Duke 1997

Cultural Marxism and Political Sociology (SAGE Library of Social Research) 1981

“Cultural Marxism and Cultural Studies,” Douglas Kellner,

http://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/essays/culturalmarxism.pdf

I found the last on my own, but it’s included on a twitter list compiled by a game tech money man ex-CEO of Milo Inc. Alexander Macris. He’s scum.

But if you want to deal in real politics you need to pay more attention.

Nobody denies that the phrase “cultural Marxism” has had different referents in the past. I linked in the post to a post by Russell Blackford that does an excellent job tracing the history of the term. Blackford suspects that folks like Lind may have borrowed the term from these earlier uses, though he doesn’t rule out that they developed it independently. Wherever he got the term, Lind’s use of “cultural Marxism” bears little resemblance to Jameson’s or Kellner’s. Kellner’s cast of characters is nearly identical to Zubatov’s. But the story Kellner tells is fundamentally different from Zubatov’s, the punchline of which is more or less Lind’s: Cultural Marxism has led to “political correctness,” man-hating feminism, and assorted other purported social ills.

At any rate, I agree with Blackford that, at this point, the term’s association with an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory makes “cultural Marxism” pretty unusable in general political conversations.

I’m not sure what the point of insulting my understanding of politics was. Your comment came very close to violating our comment policy (“ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section”), I decided to let it slip because your comment otherwise contained meaningful content. If you plan to comment in the future, please try to avoid this kind of stuff. I’m not going to let it slip again. And most of my colleagues would have been less willing to put up with it the first time.

Thanks for this instructive post Ben. I wasn’t aware of the weight “cultural” carried attached to Marxism. It does remind me of the turn via Fromm, Marcuse and others as to the resurrection(?) of Marx in the post war world. When I was an undergraduate, in the early 70’s Marx was of course discussed in political and economic terms but the cutting edge was the humanist or philosophical/psychological Marx. This was the Marx that spoke to the individual about the individual as opposed to the masses. In some ways these interpretations of Marx are much more subversive as they eschew the flamboyant revolutionary style and suggest new ways of adopting Marxian inspired ideas. Culture, in this sense, would have a rather insidious, viral meaning to those wary of any threat to the culture of capitalism.

One needs to separate the question of the issue of culture in (various) Marxism(s) — which is a complicated, interesting, and important question — from the notion of “Cultural Marxism” as propagated by the alt right and echoed by folks like David Brooks and Alexander Zubatov. Not that these things are entirely disconnected; Zubatov, Brooks, and even Lind are concerned (at some level) with actual Marxist thinkers who actually thought about culture. But they are more concerned with blaming these thinkers for a variety of perceived social ills that they are not remotely responsible for (and some of which don’t even exist). Purveyors of Cultural Marxism conspiracy theories are not engaged in a serious conversation about Marxism. And acting as if they are neither helps us understand what folks like Lind and Brooks are actually up to nor does it further discussions about culture in Marxism.