Editor's Note

This post is part of our Critical Connections series, highlighting new or forthcoming works of historical scholarship that connect to current conversations and issues of widespread concern within American thought and culture. You can read all the posts in the series by clicking on this tag/label: Critical Connections

When many of us cannot regain our composure, cannot recalibrate and reset our bearings, we reach for books.

When many of us cannot regain our composure, cannot recalibrate and reset our bearings, we reach for books.

That is one of the reasons why L.D., Sara, and I are launching the Critical Connections feature: we hope to pass along some of the codex-crutches which we are using to hobble around. It is much the same impulse that has produced the #CharlestonSyllabus and other tools for helping to aggregate and disseminate knowledge in and about the wrenching crises that are occurring with such fiendish frequency.

Reaching for books in such conditions, however, can sometimes amplify rather than dampen one’s sense of disorientation. This may be particularly true for the growing body of scholarship and book-length journalism attempting to retrace the etiology of the alt-right and internet-based hate. Often raw or slipshod in their writing and research, these books can convey a sense of panic, as if the authors were trying to dictate a last email before their cellphone battery gives out. The questions they ask often seem to be ones they formed upon first contact with the phenomenon—the primary line of research seems to be: what the hell is this?

As blunt and superficial as they can be, many of these books nonetheless traffic heavily in the history of ideas; their ultimate objective is generally to understand the growth and spread of certain idea-clusters. These books treat ideas, though, in an unusual way: they follow—and perhaps do something to perpetuate—the logic of the increasingly broad application of the verb “to weaponize.” These books treat ideas like weapons, like firearms: although one can spend time understanding their internal mechanics, the more pressing need is to find out where these weapons are aiming and how sensitive their triggers are.

This goal requires paying attention to the individuals who act as vectors for these notions and the mediums which carry them from one person to another, but the focus is—for the most part—not on the people or the platforms but on the weaponized ideas themselves. The result is a kind of intellectual-history-on-the-fly—an attempt to map rather than to interpret, to log rather than to define or distinguish. The point is to give enough history to grasp the scope of the problem, not to dig deep enough to apprehend its intricacies.

Perhaps that finer analysis will come later, and after a weekend like the one we just passed through, it’s hard not to feel the need for any kind of tool that will help us answer the “what the hell is this?” question.

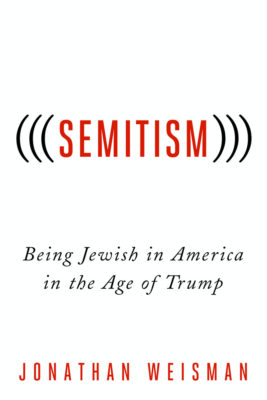

The book that I reached for in trying to steady myself after the Tree of Life shooting in Pittsburgh was Jonathan Weisman’s (((Semitism))): Being Jewish in the Age of Trump, and it shows some of the problems as well as the insights to be found in this style of instant intellectual history.

(((Semitism))) follows two parallel narratives. The first reconstructs the growth of a community of hate merchants—working online and off—as they find and radicalize one another. The second retraces the disintegration of a distinct moral voice within the Jewish community as issues of social justice—and recognition of the threat of domestic anti-Semitism—were supplanted with a single-minded, all-consuming focus on the politics of Israel. One of the most effective arguments Weisman makes is his criticism of Jewish organizations like the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Congress for their dereliction of duty as they closed down or redirected resources away from projects devoted to monitoring and combating domestic anti-Semitism and maintaining the health of alliances with other minority groups, especially African-Americans.

Weisman narrates some of this as a personal intellectual and moral awakening—he talks about his own belated and abrupt realization of the seriousness of the threat posed by anti-Semitism in America and his own lack of any kind of moral reasoning or response to it. Here is one of the passages that really stood out to me:

Jews don’t cower; we hope. Because we believe the Messiah has yet to come, we do not look back at any Golden Age. We look forward with anticipation, and we fight for our future. As the Modern Orthodox rabbi Yosie Levine wrote last year, ruminating on rising anti-Semitism and the approaching Passover, “To be a Jew is to be a beacon of hope in a world perpetually threatened by the pall of despair. The whole trajectory of the Seder leads us to the final cup of universal redemption. It impels us to see the world through the prism of what it ought to look like, but does not yet.”

That this struck me as revelatory is a painful indictment of my own thinking and a telling moment for my thinking about the Jewish community at this point in American history. I had been struggling with my own views on how to confront the alt-right when I agreed to meet Rabbi Zemel for lunch at the DC Boathouse, in what is known as “Upper Caucasia,” the very white quadrant of the District near the border of Bethesda, Maryland. A larger context—morality, the never-simple but always-important question of what is right—had not even entered my mind during this struggle. Like so many American Jews today, for me the embrace of theology does not come naturally. Zemel took no time landing on it. The moral response is imperative. Morality can inform tactics. We should certainly consider what response would be most effective: marches, vigils, lawsuits, street brawls, studied indifference. But the tactics we employ should be grounded in a principle, a belief, a morality. And American Jewry is simply not grounded at the moment.

But if Weisman couches his story as one of awakening, much of the book reads like the response of someone trying to give a lecture still bleary-eyed from sleep. There are simple editing problems—passages repeated in different parts of the book, awkward or missing transitions, arguments that really needed buttressing—but there are also parts where Weisman seems to contradict things he said earlier, or to be trying out positions he’s not wholly sure he believes. The book very much feels like the work of a person still trying to figure out what he thinks. Weisman’s feelings about political correctness, Israel, and the Republican Party, in particular, seem to be fairly fluid.

That is both rather frustrating and also completely illuminating. It is frustrating if read for answers, and illuminating if read for symptoms. Weisman comes off as a very typical Beltway insider: someone who genuinely cherishes the two-party system and finds the idea that important political changes can originate outside Washington hard to grapple with. (((Semitism))) ends up being a vivid portrayal of how Beltway journalists think.

But that is to treat the book solely as a primary text, and my purpose here was to use it to raise some questions about the recent intellectual history of anti-Semitism in the United States, and I think it does that as well. As I said above, I feel that this book, like many books that have attempted to provide a history of the alt-right, sweeps broadly but relatively shallowly across its topic. Apart from trying to understand the complexities of how Israel fits into the worldview of American anti-Semites, there is little extended examination of the writings or speeches of the alt-right. The uses of ideas rather than their structure are the focus of the author’s inspection. Most things are taken at face-value—the explicitness of their hatred seems to obviate further inquiry.

And that raises two questions: would further inquiry of the kind intellectual historians devote to complex texts be productive? And would it be prudent?

There are, of course, examples of historians and literary critics engaging closely with the ideas of anti-Semites. In the recent past, Timothy Snyder’s Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning (2015) looked to Hitler’s unpublished second book for insights into how the particular forms of his anti-Semitism directed Nazi policy toward the Shoah. David Nirenberg’s Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (2014) and Sara Lipton’s Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Iconography (2014) drew a much longer arc to demonstrate the repetition of themes (or we might even say memes) and arguments over a millennium or more. And a new book is coming out later this month with a shorter time frame: Paul Hanebrink’s A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism. These examples—and many others—demonstrate the fruitfulness of understanding the internal structures and forms of anti-Semitic ideas.

But it is one thing to write about medieval iconography and another to write about Jared Taylor or Richard Spencer, one might say. I frankly have mixed feelings about that objection, and I think much of it has to do with the uncertain boundaries between history and journalism. To me, it makes perfect sense to argue that when journalists want to write a story about the alt-right, they should not give its members a platform to spread their ideas. They should speak with researchers at organizations like the SPLC, or experts like Kathleen Belew, whose book on white power in the post-Vietnam era is probably the most definitive history we have of the deeper roots of the alt-right.

To extend that kind of editorial guidance to historians, though, would seem to be counterproductive. When a historian pays attention to some phenomenon, the effect is not the same as when a journalist puts a story about it before the public. The difference is accounted for by a whole slew of reasons that I need not itemize for you. But I think it is important to be emphatic about that difference and to stress the need for (some) historians to engage with abhorrent thought. Weisman’s larger point—that obliviousness or distraction is not security—certainly applies in this case.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

But it is one thing to write about medieval iconography and another to write about Jared Taylor or Richard Spencer, one might say.

There’s actually been considerable discussion of the overlap between medieval studies and white supremacy. Dorothy Kim, for example, published “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy” over a year ago.

Hi Andy,

Illuminating and interesting as always. Is there any discussion of whiteness in the book? It seems like part of the challenge of modern Jewishness, and one that may partly explain why Jewish organizations have struggled to build and sustain networks with African Americans, is its peculiar relationship to whiteness in an era of resurgent (or at least increased coverage of) white supremacy.

Thanks for the review.

Matt

Jonathan,

Excellent point. I should have made clear that I wasn’t putting forward that argument myself–“one might say” was meant more in the spirit of “some have said.” I’m familiar with the work by Kim and a number of other scholars to convince the medievalist community to take the appropriation of medieval symbols and texts more seriously.

Matt,

Great question. That’s not someplace Weisman tries to go–at one point, he even parenthetically adds “(Yes, in the minds of the alt-right, Jews are not white, all appearances aside, an old racist concept regaining an airing in the Trump era.)” I think you’re totally right that Jewish-Americans’ vexed relationship to whiteness is a part of why these national organizations have struggled to see the connections to other minority communities. There is a historical memory that once upon a time Jews were not white, but near total disbelief that the process which whitened them might be reversible. And, I would speculate, there is a great deal of pride in having “made it”–and that pride is a major stumbling block in trying to forge coalitions and feel true solidarity with African Americans and Latinxs, in particular.