A few Saturdays ago, just after sunset, a sizable chunk of downtown Dallas was converted into a giant public outdoor art event. It was a biennial exhibition of installations combining light, sound, and video that goes by the name AURORA. Maybe the noise and anguish of the midterms had inhaled my attention, but it almost got by me. Then I happened to catch one of the curators being interviewed on the radio the day before. Her description of the exhibition’s theme intrigued me.

“Whether dystopian or utopian, sci-fi or retro-futuristic,” I later read in the program, the artists were aiming “to open a dialogue about how we collectively envision our Future Worlds.”

During the past few years, I’ve devoted a good deal of time to readings in environmental thought, mainly that of academics, scholars, and public intellectuals. At times I feel a kind of sameness setting in. Arguments tend to stall before a similar set of conundrums. A transformation of values is called for to readdress “our attitude toward the problem of physical reality.”[1] Yet our means for doing this seem of necessity to be based on old metaphors, faulty narratives, and obsolete modes of perception.

This was why the theme “Future Worlds” intrigued me. When it came to envisioning a radically different future, were the artists doing any better than all those writers of discursive prose?

We caught the streetcar downtown the next evening.

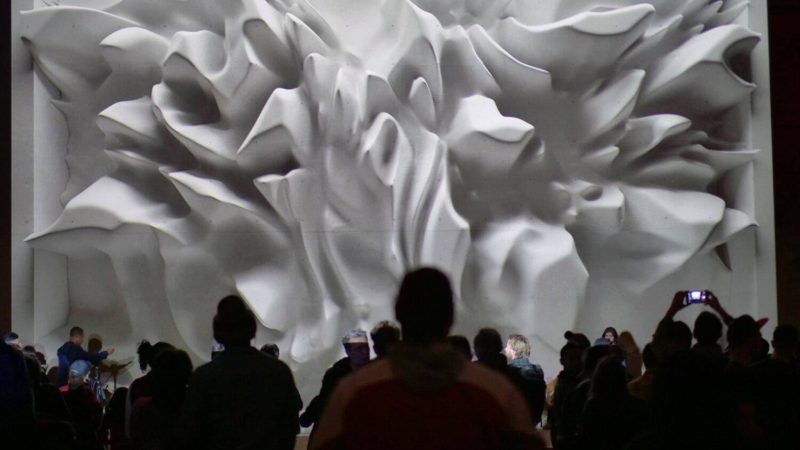

The first two installations we saw set the terms of the exhibition and offered answers to some of my questions. “Melting Memories,” by Refik Anadol, was a projection of light against a back wall of the city hall building. The image was of an enormous, shallow box, set on its side, so that viewers would look directly into it. Inside was a continually morphing topography of fluid, foamy sand. What governed its constant movement? Anadol had gathered “data on the neural mechanisms of cognitive control” from a machine that “measures brain wave activity” and somehow rendered it into an algorithm.[2] This wasn’t a record of something that had happened in the past. This was something that seemed to be happening in the moment. To be frank, it looked alive.

“Melting Memories” by Refik Anadol. Photo: https://www.facebook.com/dallasaurora/

Coming around city hall to the vast public plaza out front, we literally stepped into the second installation. It was another projection, this time not against a wall but across a rectangular portion of the plaza itself. This piece, called “Digital Icons,” was described as “a giant light carpet” made of many-colored icons, familiar from “the early days of the computer era.” These icons appeared and disappeared around our feet, creating new patterns as we walked across them, responding differently to each of our individual steps.

“Digital Icons” by Miguel Chevalier. Photo by Cole Chaney.

The patterns moved around our feet; the people moved within the rectangle. Outside the rectangle, crowds were moving, too–across the plaza, the green spaces, the sidewalks and streets, gathering at and moving away from the glowing obelisks that marked each installation. If you could claim a perch that was distant enough to take it all in, the shapes you saw would be constantly moving, like the glowing sand in the sandbox, which was based on brain waves, on thought.

I paused to take stock. What did these shapes have in common? Open-ended motion. Unpredictability. Asymmetry–they were absorbing but not conventionally beautiful. A number of films had come to mind. One from long ago, the famous Koyaanisqatsi, disrupted commonplace perspectives by playing with film speed and other visual devices. The more recent Mother! combined fable with a similar acceleration of narrative time. In Annihilation, also recent, an alien presence breaks down barriers between organs, organisms, and species. All the hard divisions we’ve come to depend on are compromised. A scientist’s journey to investigate becomes one not of conquering an enemy but of overcoming repugnance at what she finds.

In each of these examples, technology is used to appropriate a natural dynamic in order to make visible something formerly unseen. The most direct of AURORA’s installations was one by Fabian Knecht, called “Freisetzung (Release).” Again the city hall building was used, this time the roof, from which a dense white smoke was somehow being emitted. The smoke billowed “freely for some time before dissipating.” As it did so, it changed continually “in terms of orientation and color to the given atmospheric conditions.” Again, all the characteristics I’ve described were on display: the unpredictability, the asymmetry, the ability to mesmerize and soothe. I could have stared at the smoke for quite a long time, as around a campfire I’ve stared for hours at flames.

Freisetzung (Release) by Fabian Knectht. Photo by bPaperlytete.

The program had used the term “dystopian,” but so far, these installations were all heart. They imagined futures that we could be a part of, if we could overcome resistance, expand our notions of what’s beautiful and what’s lovable, like the scientist in Annihilation does. Where was the unassailable threat and dread we typically feel when thinking about technology, climate change, and contemplating the future?

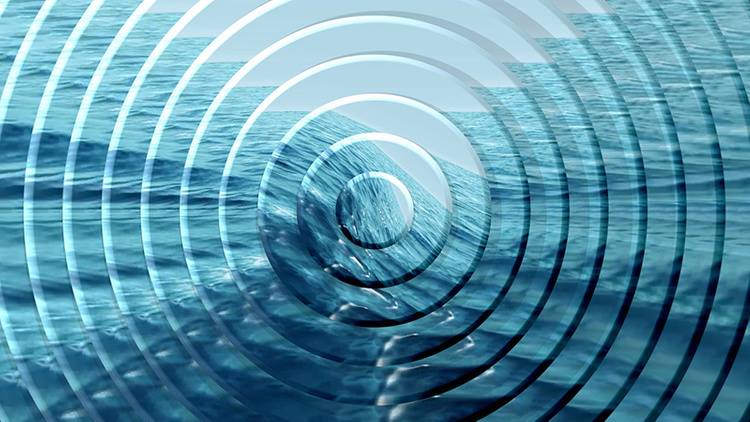

Kristin Lucas’s “Sick Waves,” the only piece that explicitly mentioned climate change, fed the interpretation I was moving toward. This was a light projection, too, but otherwise unlike the other pieces I’ve described. A series of concentric circles were programmed to place the viewer inside the formation of an ocean wave: to build, to spin, to crash, and then to start all over again. Of course, no real wave is so uniformly repeatable. None have that kind of perfectly balanced precision. These waves were sick, like the present we’re trying to imagine ourselves out of.

“Sick Waves” by Kristin Lucas. For more information on this artist, http://ow.ly/FKuz50jhKu1

Later that week, I was back to reading discursive prose. In a section of his 2017 book, Out of the Wreckage, environmentalist-journalist George Monbiot challenges the notion that an individual’s political principles are arrived at by rational means. This may be important to historians and other writers of discursive prose, we who prize rational argument and who are understandably wary of those who don’t. Yet people don’t put their political selves together rationally, Monbiot argues. They look to the community around them, and they try to belong. This isn’t necessarily a negative. “If we perceive ourselves to belong to a community in which people work together, to improve their lives, and then neighborhood, to enjoy each other’s company and help each other, that perception is likely to shape our political self-image.” Such an image could take the quality of a contagion.

I wondered about the verbs Monbiot uses in this sentence: feel, believe, say, belong; work, improve, enjoy. I tried to imagine these actions and the thread between them as shape in movement. Aesthetic experience has a way of re-wiring the brain.

____________

[1] The phrase is physicist David Bohm’s, quoted in Best and Kellner, The Postmodern Turn

(New York: Guilford Press, 1997), 215.

[2] Unattributed quotations come from the exhibition’s program, found at the event website: https://dallasaurora.com/

0