Editor's Note

This is the paper I presented at the recent S-USIH conference in Chicago. It is based off of my book project entitled “Republic of Mirth: Humor, Settler Colonialism, and the Making of a White Man’s Democracy, 1750-1850.”

I would like to thank the other panelists, Emily Masghati for her great paper “‘For the Well Being of Mankind’: The Rosenwald Fund Fellowship Program and Transformations in American Foundation Philanthropy, 1928-1941,” and Susan Pearson our chair and comment for her insightful comments and her ability to convince us all that our papers indeed belonged on the same panel.

In the spring of 1815, a few months after the treaty of Ghent had finalized the War of 1812 between the United States and Britain, a suggestive comical song circulated in American newspapers about the Battle of New Orleans. Using the emerging genre of black dialect minstrel songs, it related the events of the recent battle from the alleged the perspective of a runaway slave who joined the British side and partook in ensuing events. The first stanza related the slave’s journey from Africa to Virginia and finally to the British side during the war:

When me leetle boy, den me sum from Guinea,

Buckra man teal me, bring me to Virginia;

Dare me very much work

Great big fence-rail toat-e—

But British man he come,

He give me fine red coat-e

The third stanza portrayed what happened once they landed in New Orleans and engaged with the American troops:

When we come ashore, great big gun we shoot-e

For make Yankee run, den we could get de “booty”

But de backwood Yankee,

He not much good nater,

He say he ‘one half horse,

Half an alligator!’ (1)

This little known song, I would like to argue, was an historical meeting point between the two iconic clowns that would come to loom large in American popular culture in the decades following the War of 1812—and in many ways both are still very much with us. These two are the black minstrel, the narrator of the song, and his purported interlocutor in the Battle of New Orleans, the frontier jester captured above by the phrases “backwood Yankee” and “one half horse, Half an alligator.” Their respective paths would for the most part diverge from here on out, with each of them commanding their own genre. The black minstrel would become the center of the genre of blackface minstrelsy that would develop over the following decade and explode unto the American scene in the 1830s and 1840s. Likewise, over these very years the legend and tall tales that had long accumulated around half fictional half historical figures such as Daniel Boone and later Davy Crockett, Mike Fink, Kit Carson and many more, would also emerge as a popular-culture genre that would find its expression in dime novels, comic almanacs, stage performances and more.

Yet in order to make sense of the cultural work they performed in the antebellum period, I argue that we must view them together. For in fact, as the song I opened with hints, they both originated in the cultural project that complemented the recalibration of the American body politic in the wake of the War of 1812 around manhood and whiteness. We should therefore view them as foils for each other. In other words, the era of the common white man—as captured by the idealization of the frontier jester—must be understood to the backdrop of the emasculation and marginalization of black men through enactments of black minstrelsy.

Clowns became a well-known trope in the British-Atlantic world over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Tapping carnivalesque vernacular traditions that date far back into pre-modern European societies, they offered British peoples the perfect foils for fleshing out a cluster of anxieties about class status, ethnicity, and gender in a highly stratified society undergoing seismic economic and social changes. Such carnivalesque energies allowed clowns to become a suggestive tipping point that vacillated between reinforcing social mores and subverting them. In an early modern British Atlantic world that saw a transition to republicanism, the rise of market forces, migrations from provinces to metropolitan centers, as well as the forced migration and enslavement of African peoples, traditional seams along which power operated—most importantly class status, gender, and race/ethnicity—were in transition. Tropes of the clown from this period, not incidentally, induced mirth by intervening along all three axes of power.

The country clown was ubiquitous in this period, appearing in jest books, theater, literature, and song. In jest books country bumpkins often appeared as provincial buffoons who were to some degree the butt of the joke, but usually also induced even more mirth by “upping the ante” and undermining to some degree metropolitan city ostentation. Referred to either as a country man, a country clown, or at times an Irishman, or Yorkshireman, as well numerous other designations that conjured the image of a crude provincial bumpkin, the interlocutor in the jest was often a haughty city gentlemen. In the ensuing comical altercation both usually suffered to some degree, functioning as the target of the jest, and thereby fleshing out the myriad traits inherent to each position. While the country clown was crude, dim-witted, and ignorant, he boasted a certain simplicity of character and a common-sense, child-like perception of the world that carried some weight in a society anxious about corruption and effeminacy. And while the city gentleman was more sophisticated, learned, and urbane, he was prone to effeminacy, corrupt ostentation, and often turned out to be a cuckold: unmanned not only to some degree by a provincial clown, but more ominously by his woman.

In Britain, where elites had access to numerous resources, such tropes did not fundamentally challenge long established hierarchies; but in the American colonies and in the early American republic such carnivalesque tropes converged with a revolutionary upheaval that challenged the much less established class hierarchies of British North America. Thus in the wake of the war the gentleman-planter and greatest hero of the Revolution, George Washington, had to share the stage with an Americanized version of a country clown, the Yankee Doodle. Indeed the most famous Yankee Doodle versions of the Revolution poked fun both at the Yankee bumpkin and Washington and his polite entourage.

As the center of gravity shifted in the young American republic westward, geographically, and towards the common man, politically, the Yankee clown mutated into the frontier jester. The focal point of that transition was the War of 1812 and especially the Battle of New Orleans. Just as the war erupted in 1812, James Kirke Paulding launched his career of literary nationalism by publishing The Diverting History of John Bull and Brother Jonathan, an amusing narrative of the rising hostilities between the British and the United States. Unfolding the events leading up to the war from a pro-American perspective, it used the trope of the Yankee clown—that had by then also become known as Brother Jonathan—as the embodiment of the nation.

By contrast, as the song above suggests, by the end of the war the heroes of the Battle of New Orleans were backwoods Yankees, also referred to as “one half horse Half an alligator.” And by the time the more famous song “The Hunters of Kentucky” became a hit in the early 1820s it enshrined the heroes of New Orleans without mentioning the word Yankee altogether. Here is the first stanza of Samuel Woodoworth’s hit song:

We are a hardy, free-born race,

Each man to fear a stranger;

Whate’er the game we join in chase,

Despoiling time and danger

And if a daring foe annoys,

Whate’er his strength and forces,

We’ll show him that Kentucky boys

Are alligator horses (2)

By the early 1820s when the famous performer Noah M. Ludlow performed the song in frontiersman garb in front of packed houses, the moniker “alligator horse” became a badge of honor for American backwoodsmen, who would become increasingly known as frontiersmen. This trend was reinforced by then by the anti-war stance of many in New England during the War of 1812 that had rendered the word Yankee a liability of sorts in the rest of the country following the war.

The success of the phrase “half-horse, half-alligator” perhaps best captures the rise of frontiersmen—and their expression in jester form—in public imagination. The earliest two mentions I found of the phrase, both in reference to crude frontiersmen, appeared in Washington Irving’s comical History of New York from 1809 and Christian Schultz’s accounts of his western travels in 1807-8 and published in 1810. Though not unfavorable, both appear ambivalent about the character of American frontiersmen and attribute at least some derogatory meaning to the phrase, and by implication to clownish and violent frontier types. As is quite clear, by the end of the War of 1812, after the Battle of New Orleans, when Americans sought to capture the virility of the frontier and its uncanny capacity to unman British ostentation, they turned to that very phrase. This time they imbued it with a much more favorable connotation that harkened back to the strategy of self-affirmation through carnivalesque humor that had made the “Yankee Doodle” song and character so successful during the Revolutionary period.

This very dynamic seemed to repeat itself when the iconic theater Yankee quite literally morphed into the frontiersman about a decade after “The Hunters of Kentucky” first captured Americans’ imagination. In 1830 James Hackett, who had made his fame as a specialist in Yankee stage performances, looked for fresh material and placed an advertisement in the New York Evening Post that offered a prize of $250 for the best comedy “dramatizing the manners and peculiarities of our own country.” Inspired by the news of David Crockett, the peculiar frontiersman who had recently arrived to take his seat in Congress, it was once more James Kirke Paulding that rose to the challenge. The result was the play The Lion of the West tailored for Hackett as the lead role of the frontier jester Nimrod Wildfire of Kentucky, which won the competition. Debuting successfully in April 1831 before a full house at New York’s Park Theater, one reviewer commended Paulding for “an extremely racy representation of western blood, a perfect non-pareil—half steam-boat, half alligator.” “The body and soul of Col. Wildfire,” he stressed “was Kentuckian—ardent, generous, daring, witty, blunt, and original.” “The amusing extravagances and strange features of character which have grown up in the western states, are perhaps unique in the world itself,” concluded the author of the review.(3)

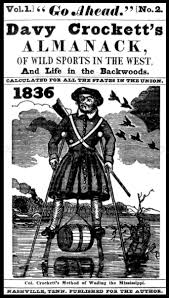

This is the cover of one of the famous Crockett almanacs (this one is for the year 1836) that capture well the imagery of the frontier jester.

The play The Lion of the West saw much success on both sides of the Atlantic, while over the 1830s numerous versions of the life of Davy Crockett made his character famous, especially once he died in 1836 in the Battle of the Alamo. And by the election of 1840 William Henry Harrison obtained the presidency by casting himself in the mold of frontier jesters, living in a frontier log cabin and drinking hard cider. Here are two stanzas from a song that captures the spirit of Harrison’s notorious Log Cabin campaign:

Ye jolly young Whigs of Ohio,

And ye sick “Democrats” too,

Come out from among the foul party,

And vote for Old Tippecanoe

They say that he lived in a cabin,

And lived on old hard cider too;

Well, what if he did? I’m certain

He’s the Hero of Tippecanoe.(4)

In the election of 1840 the Whig party successfully flipped the script on the party of Jackson. By nominating Harrison, a famous denizen of the west and a hero of the War of 1812 and the Battle of Tippicanoe, and casting him as the true inheritor to Andrew Jackson, they won the election. Though hand picked by Jackson to succeed him, the Democratic incumbent, Martin Van Buren could not successfully defend himself from accusations of being an easterner and a lifelong political insider. By 1840 even the Whigs had to masquerade as the heroes of the common man.

The story of the rise of the black minstrel also had much to do with carnivalesque explorations of the power structure in the British world. This time however the category of race loomed far larger than those of class or gender, though both too were surely wired in a host of ways into the manifold black minstrel characters. The difference in this case was that blackness, like Irishness in parallel cases, had been introduced to curtail the subversive potential of the clown. For all their carnivalesque potential, ethnically or racially hued clowns could never seriously challenge the power structure, and usually ultimately served to reinforce it.

Black clowns started appearing in the British world over the eighteenth century. One early example was Friday, Robinson Crusoe’s racy—and racialized—companion. Furthermore, in jest books, literature, songs, and in theater from the period we can find numerous mentions and renditions of black slaves. Much like other ethnic clowns from the period, especially the Irish clown, with time they were often endowed with a recognizable black dialect.

Here too it is not surprising that the fate of the black minstrel loomed larger on the west side of the Atlantic than in the British Isles, for the presence of African American people as well as the institution of slavery were far more ubiquitous in the Americas. Moreover, as the American Revolution helped release radical notions about inalienable rights into the air, Americans groped for novel ways to discipline the borders of the body politic along newly imagined lines. As the white clown continued to do the work of defining the borders of the republic positively, expanding the polity to include all common white men, there was a complementary need for carnivalesque humor to define the borders of the polity negatively, by excluding everyone else.

It is therefore no coincidence that the first black dialect songs started appearing during the War of 1812 as well, and that one of them, with which I opened this paper, even saw a pitched battle between the black minstrel and the frontier jester. Indeed, historians consider the song “Backside Albany,” written and popularized in the wake of the Battle of Plattsburgh over the winter of 1814-15, as the first blackface minstrel song. Using the voice and dialect of a black sailor, it appeared in numerous songsters from the period and was performed in blackface just a few weeks after the American victory in Plattsburgh. Thus, after an even greater victory a few months later at New Orleans, it is no surprise that at least one author sought to parallel the success of “Backside Albany” with a black dialect song of their own.

Given the contours of the body politic emerging in the wake of the War of 1812, it is also no surprise that one of the stanzas of the dialect song opening this paper also made a reference to a “pretty garl” with which the narrator expected to have “plenty of fun-e.” According to the song, this insidious intent was, of course, also rebuffed by the brave heroes of New Orleans. Similarly, “The Hunters of Kentucky” also cast “Kentucky boys” as protecting “ye ladies” from the depredations of the British invaders, allowing the American victors to “enjoy” all the “beauty” of New Orleans, which a pervious stanza cast as running the gamut from “snowy white to sooty.”

Indeed, as a resurgent nationalism swept the nation in the years and decades following the War of 1812, the different artifacts of contemporary popular culture converged to cast a mental image of the nation along implied, but clear, racial, gender, and class lines. White common men were designed to appear in the foreground as the upright citizens of the republic, while women occupied the background. Racial others, who white virile men supposedly protected women from, lurked on the margins, as the foils against which white manhood demonstrated its prowess.

Thus in the 1830s and even more so in the 1840s, as Americans constructed a national popular culture to a large degree around these two iconic clowns, the borders of the American nation would become ever more “self evident,” to burrow Jefferson’s telling phrase. Employing such carnivalesque formulas to flesh out the meaning of the national character, Americans etched basic assumptions about the nature of the nation, citizenship, and polity deep into the communal subconscious. From here on out, when thinking about what they mean when alluding to ideas that are basic to the nation, such as “America,” or “Freedom,” Americans would conjure a host of images framed to a large degree by these carnivalesque tropes.

Notes

[1] See for example “Poetry,” New Jersey Journal (Elizabethtown, N.J) 4/25/1815.

[2] “Poetry,” Ladies Literary Cabinet, 2/10/1821, New Series, Vol. 3 (New York: Brodrick and Ritter, 1821), 112.

[3] Quote taken from Aderman and Kime, Advocate for America, 136.

[4] The Harrison Medal Minstrel: Comprising a Collection of the Most Popular and Patriotic Songs (Philadelphia: Grigg & Elliot; Hogan & Thompson, 1840), 102-4.

0