The Book

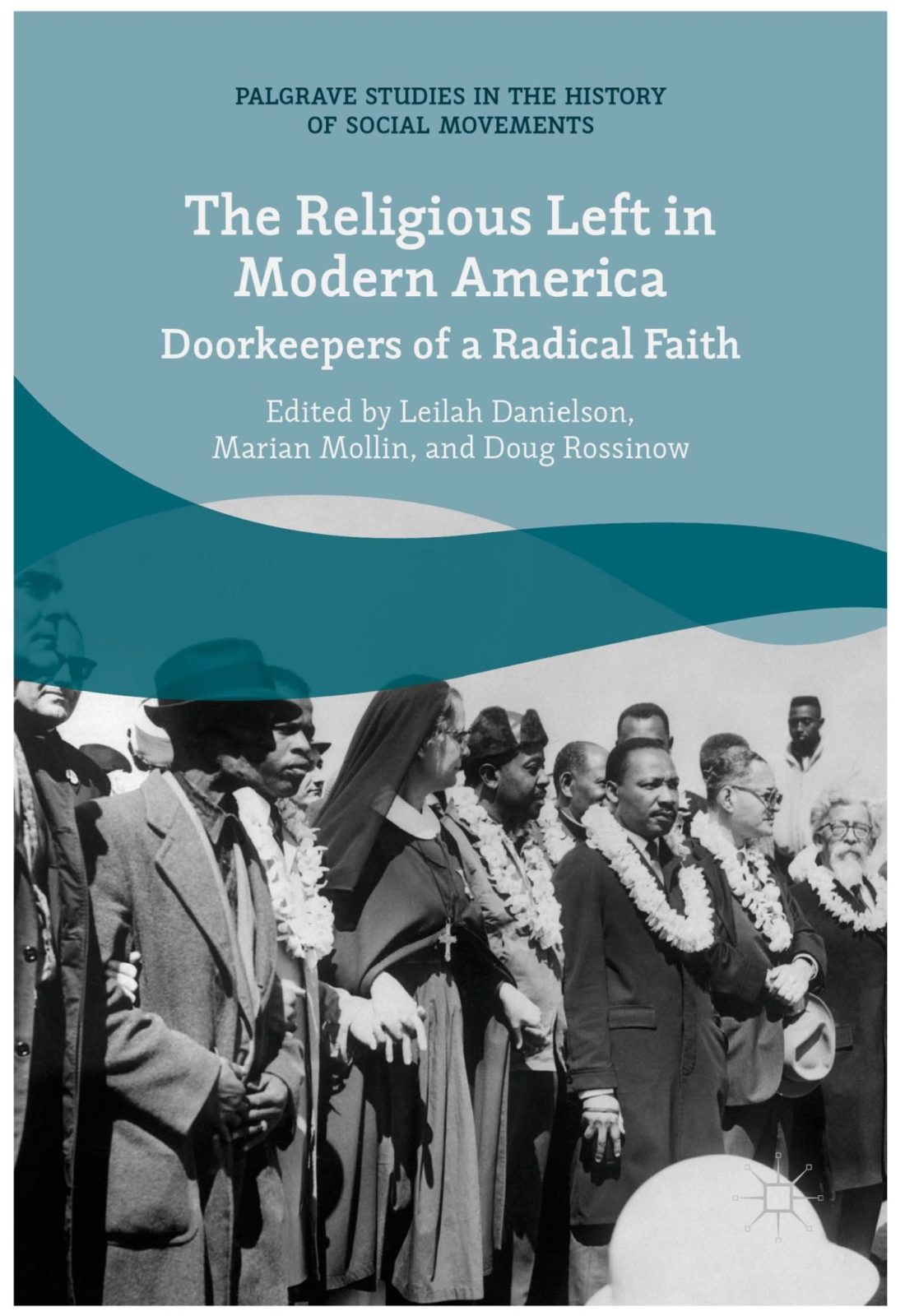

The Religious Left in Modern America: Doorkeepers of a Radical Faith

The Author(s)

Leilah Danielson, Marian Mollin, and Doug Rossinow . Leilah Danielson, Marian Mollin, and Doug Rossinow

The revival of a so-called religious left in the past decade has received a lot of attention recently in popular publications such as the New York Times, Reuters, and the Washington Post. Most of these accounts, however, do not detail the rich history of this tradition, which once wielded a considerable influence over American politics and culture. The editors of the enlightening collection of essays in The Religious Left in Modern America: Doorkeepers of a Radical Faith

aim to set the record straight, challenging misconceptions about American religion, radicalism, and culture. The spectrum of American political activism, they aptly show, does not easily divide between the secular left and the religious right. They delve into the complexity of religious and political history in the US and offer a much-needed resource for understanding the long-standing religious left and its organic development in American culture.

Even familiar topics such as the social gospel get a fresh treatment in many of the collected essays in this volume. The authors acknowledge the conventional interpretation of the social gospel as a mostly middle-class phenomenon led by liberal clergy, but they expand the canon of activists who expounded social gospel values at the radical edges of American politics. For example, Janine Giordano Drake, in her contribution entitled “The Other Social Gospelers,” chronicles the working-class activists who allied with and rivaled liberal social gospelers at the turn of the twentieth century. “The religious left,” she argues, “both predated and outlasted the Social Gospel movement” (21).

This, of course, depends on whom you ask. Christopher Evans, another contributor to this collection, has written about the staying power of the social gospel movement beyond its “classic” pre-World War I phase. In his essay, “The Social Gospel, the YMCA, and the Emergence of the Religious Left After World War I,” he gives due credit to the YMCA for disseminating social religious ideas among a network of activists, including liberal social gospelers and more radical religious leftists. Since delineating between liberals and radicals in any political tradition often proves tricky business, the ability of these scholars to navigate the contours of overlapping historical narratives is admirable. David R. Swartz’s essay on “global encounters,” immigration, and the reverse evangelizing of Christians coming to the US, for example, makes a powerful, original contribution, altering our preconceived notions about American Christian exceptionalism.

Another remarkable achievement in this volume amounts to the diversity they include while retaining a discernable baseline. A number of essays, in fact, focus on race and gender in ways that challenge assumptions about Black Power, the Jewish left, or feminism, traditions typically thought of as solidly secular. But, as David Verbeeten argues in his essay on “Judaism, Yiddish Peoplehood, and American Radicalism,” “the influence of religion need not be straightforward, orthodox, or literal. It can be derivative” (62). Following up on this theme, contributors Angela D. Dillard, Lillian Calles Barger, and Doug Rossinow analyze the religious elements that permeated Black Power, feminism, and Jewish activism, respectively. Religion, in short, need not be relegated to the dustbin of identity politics.

For all of its virtues, however, this collection does fall short on a few issues. As the editors readily concede in the introduction, their book is not a comprehensive survey of the religious left, but rather a fragmented collection of moving parts, a fact that makes it more difficult to pull together a clear narrative. Some scholars may question their periodization of the rise, crisis/fall, and revitalization of religious left, though debate on this point is most likely welcome, and not set in stone. Perhaps most importantly, this collection does not adequately address how the religious left relates to Communism and socialism. Communism is mentioned only in passing as an unfortunate source of red baiting for many religious leftists, even if they had no affiliation with the Communist Party. And, other than Drake’s essay on the working class in the early twentieth century, few if any of the essays mention religious socialists, and none analyze them seriously. This is a crucial topic of historical investigation. In order to understand how socialism evolved from a top-heavy, labor-oriented movement into a democratic, moral project by mid-century, scholars must analyze the role of the religious left and its relationship to socialism.

Yet the editors of The Religious Left in Modern America have done a great service by opening up an overdue conversation about the interplay of religion and radicalism. After all, we cannot expect to bridge divisions in the present until we bridge them in our past.

About the Reviewer

Vaneesa Cook is the Bader Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of History at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and her dissertation is titled “Thy Kingdom Community: Spiritual Socialists and Local to Global Activism, 1920-1970.”

0