In preparation for a paper for the S-USIH Conference in November, I read a lot of Arthur Koestler this summer–and I read some about him, too. Koestler’s prose was good company. He had a gift for writing about ideas. I’m not sure I would have enjoyed spending much time with him in person.

One essay I returned to more than once was “The Yogi and the Commissar” from 1942. It’s a good example of Koestler’s ability to capture concepts in figurative language. He begins by imagining a device able to break down the spectrum of “all possible human attitudes to life” into bands of light—a “sociological spectroscope,” he calls it. At one extreme end is the infra-red, represented in Koestler’s scheme by the Commissar. The Commissar is the ideologue, willing to take bold action, including “violence, ruse, treachery, and poison,” to achieve the goals his doctrine prescribes. Representing the opposite ultra-violet end of the spectrum is the Yogi. The Yogi’s highest value is his spiritual attachment to “an invisible navel cord” through which he is nourished by “the all-one.” The Yogi “believes that nothing can be improved by exterior organization and everything by the individual effort from within.”

I attempted to describe a similar change-from-without/change-from-within confrontation between radicals in the late sixties in my book, Runaway: Gregory Bateson, the Double Bind, and the Rise of Ecological Consciousness. For illustration, I relied on Marat/Sade, Peter Weiss’s play of the period, but found many other contemporary attempts to express a similar argument. I’m almost certain I’d read “The Yogi and the Commissar” at some previous point, but by the time I got around to writing, I must have forgotten about it. How hard I worked to keep those sections light and swiftly moving! Koestler’s writing seems so effortless on the page that I can only shake my head in admiration.

If reading Koestler was easy, I was often made uneasy reading about him. Face to face, he could be competitive and overbearing. Sidney Hook said Koestler “could recite the truths of the multiplication table” in a way that made people angry. Then there was his treatment of women. Koestler was known for his “crude advances” and a “predatory belief that coercion added spice to sexual intercourse.” At least one woman accused him of rape. Certainly, Koestler had several long-term relationships, but he tended to organize the energies of the women who loved him in secretarial work to advance his literary cause. In his seventies, suffering from Parkinson’s and leukemia, Koestler committed suicide, and was joined in the act by his third wife Cynthia, who was healthy and fifty-five.

To sum up: When we turn Koestler’s spectroscope on his own sexual relations, we get a strong reading of infra-red. His ends justified his means, as they do for the Commissar.

Arthur Koestler in 1969. By Eric Koch / Anefo – Nationaal Archief, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35304960

The above impressions, as well as the quotes, are drawn from my reading of Michael Scammell’s 2009 biography. Scammell tells a good story, too. As for the rape charge, he doesn’t simply accept it at face value. He tries to place it in context; he airs a number of considerations. For instance: Koestler’s accuser did not speak immediately about the assault but waited for many decades to pass. She “seemed to have responded by pushing the incident to the back of her mind and accommodating herself to it.” Perhaps what Koestler did wouldn’t have been called rape then, but has only been described that way more recently. Koestler made no mention of the incident in his diary, though his diary was the place he regularly listed conquests. On the other hand, Koestler was drinking a good deal during this period, so it’s possible “he was so drunk he forgot all about it.” These considerations, read in light of the Kavanaugh scandal, ring out with familiarity and thud like punches to the gut.

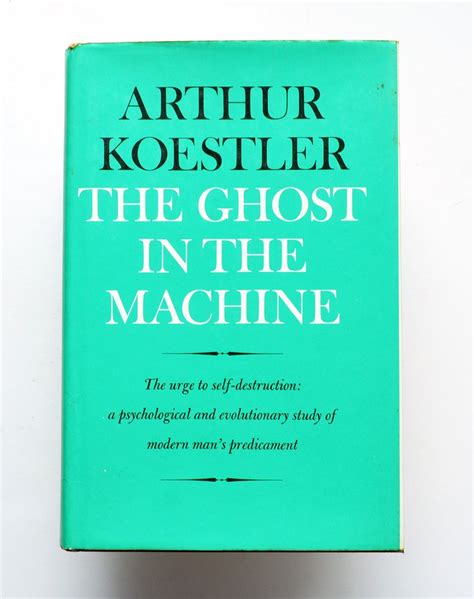

In his 1942 essay, Koestler denied any smooth blending somewhere in between the ultra-violet Yogi and the infra-red Commissar. “Apparently the two elements do not mix”; all that “has been achieved so far are various forms of motley compromise.” Two decades later, however, when he brought his intellectual concerns to the sciences and to metaphysics, Koestler allowed himself to imagine a less motley merger. This becomes explicit in The Ghost in the Machine (1968), the last book of a trilogy that includes The Sleepwalkers (1959) and The Act of Creation (1964). Applied not merely to human behavior but to the nature of things in general, the attitudes of the Yogi and the Commissar become opposing “tendencies” or “potentials,” one integrative and the other self-assertive. At certain levels of systemic organization, where entities function as both part and whole, the integrative and the self-assertive occupy the same space, embroiled in “dynamic equilibrium.” Koestler belongs in a tradition of thinkers who sought a grounding for individual and public morality in a synthesis of nature and culture and who strived to describe the living world as a moral environment where the choices of individuals make a difference.

In his 1942 essay, Koestler denied any smooth blending somewhere in between the ultra-violet Yogi and the infra-red Commissar. “Apparently the two elements do not mix”; all that “has been achieved so far are various forms of motley compromise.” Two decades later, however, when he brought his intellectual concerns to the sciences and to metaphysics, Koestler allowed himself to imagine a less motley merger. This becomes explicit in The Ghost in the Machine (1968), the last book of a trilogy that includes The Sleepwalkers (1959) and The Act of Creation (1964). Applied not merely to human behavior but to the nature of things in general, the attitudes of the Yogi and the Commissar become opposing “tendencies” or “potentials,” one integrative and the other self-assertive. At certain levels of systemic organization, where entities function as both part and whole, the integrative and the self-assertive occupy the same space, embroiled in “dynamic equilibrium.” Koestler belongs in a tradition of thinkers who sought a grounding for individual and public morality in a synthesis of nature and culture and who strived to describe the living world as a moral environment where the choices of individuals make a difference.

A passage comes in The Ghost in the Machine where Koestler raises “the moral dilemma of judging others.” He has developed an argument in which “the self-assertive, hunger-rage-fear-rape” emotions constrict “freedom of choice.” The loss of freedom in Commissar-like behaviors involve “the subjective feeling of acting under a compulsion.” “How am I to know,” Koestler asks, “whether or to what extent [a person’s] responsibility was diminished when he acted as he did, and whether he could ‘help it’?”

Was he thinking his own behavior here? And if so, was it merely an excuse, a self-serving dodge, or did it have an element of truth?

In Ronan Farrow’s reporting–a year ago, now–we find indications of compulsion in the actions of Harvey Weinstein. After one of his victims went to the police and subsequently wore a wire, Weinstein’s behaviors subsided, a former employee explained. “But he couldn’t help it,” she went on to say. “A few months later, he was back at it.” Donald Trump, too, is often described as having no impulse control. These men see themselves as absolute sovereigns of their worlds; they have severed “the invisible navel cord,” their connection to a larger relevance; they have ignored the pushbacks in their environment for so long that it’s now a habit they can’t break. The paradoxical outcome is a lack of control. Thenceforth, they can’t help but be destructive and vile.

As for “the moral dilemma of judging others,” I understand Koestler’s question, but I’m not sure it’s a useful one. Taking a systems perspective blurs boundaries, including those between self and environment, between us and them, between victim and victimizer, but it doesn’t follow that matters of justice be abandoned or that victimizers be let off the hook. Given time, I suppose, individual cases can be contemplated with scholarly dispassion, as Michael Scammell did with Koestler himself. As for now, it would probably be safer for everyone that the power addict’s power be removed.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Anthony,

I haven’t read The Ghost in the Machine but my second-hand impression has been that it’s, among other things, a critique of behaviorism in psychology (or at any rate, a critique of what Koestler took to be behaviorism). Just wondering how much he discusses in that book the main psychological ‘schools’ of the time and how, if at all, that intersects with the post, e.g. on questions of individual responsibility, judging others, etc.

Thanks for the question, Louis. The first few chapters of The Ghost in the Machine are an attack on behaviorism, which is Koestler’s go-to example of what he calls “flat-earth science.” His brief aside about the problem of judging those who act out of compulsion comes much later, toward the end. One way to understand the thread between the two would be to think in terms of the “sociological spectrum” from his Yogi/Commissar scheme: he places behaviorism on the ultra-red side of the spectrum and gestalt psychology on the ultra-violet side.

thanks

Anthony, thanks for this challenging post. I was talking recently with a colleague about an academic who lost his job in the wake of the #MeToo movement. I said, “I cannot help but feel pity and grief for someone who managed to mess up his own life so badly while also messing up the lives of others.” My interlocutor was not having it. “That guy was abusing his power in a job that could have been filled by someone else,” they said. And that’s true.

I don’t always feel pity and grief in these situations — no sympathy for Weinstein, no sympathy for Kavanaugh, no sympathy for Pogge or Searle or any of the other recent infamous cases. My empathy meter is registering at zero for all those guys. But my interlocutor’s comment made me interrogate anew why I would feel sympathy for anyone in a position of power who abused it to try to compel subordinates to provide them with sexual / emotional / erotic gratification. What’s that about?

I think some of it is what Kate Manne has identified as “himpathy” — the culturally-conditioned impulse to feel regret and sorrow and to make allowances for men who fail ethically or morally. Some of it is a chastened awareness that “all have sinned…” — that if I cannot picture myself or anyone I know and trust engaging in such abusive behavior, that doesn’t mean that I am not capable of some other, equally egregious failing. Some of my pity and grief is probably residual “Stockholm syndrome” from my own experiences of being on the receiving end of such predatory behavior. And some of it is a generalized sorrow that such things happen — a kind of grief and pity for the human condition. That things are sometimes this way is grievous, and it weighs on me.

As to earlier ideas about what may or may not have constituted rape, here’s an interesting data point from that (understudied) manifestation of mid-century American thought, Peyton Place by Grace Metalious.

A pivotal scene in the novel includes what we would describe today as “date rape,” where the dashing and handsome Tom Makris physically overpowers the single mother he is dating and over her protestations takes her to her bedroom and has his way with her. As she struggles, she says, “I’ll have you arrested…I’ll have you arrested and put in jail for breaking and entering and rape–” at which point he slaps her hard across the face and tells her to be quiet. The experience is described as “a nightmare from which she could not wake” until she recognized beneath her sense of shame a sense of pleasure.

This is obviously problematic, a typical bodice-ripper assertion that women secretly enjoy being forced (which itself comes from a long tradition of thinking about women — see, e.g., Machiavelli.) At the same time, within the context of the narrative, this single woman has entertained this suitor in her home numerous times and has gone out on dates with him in view of the whole town, and yet is not hesitant to call what he is doing to her “rape.” And it is portrayed as rape.

So I don’t think the “these things were understood differently” explanation would work for Koestler.

We are confronted with the perennial problem of the interconnectedness (or the deliberate separation) of ideas from lives, art from artists, etc. I saw that Roman Polanski is “making the first film about the #MeToo movement.” What in the world does Roman Polanski think he can say about this? Is the whole film just going to be Polanski talking to his reflection in a mirror?

I’d rather watch another “Avengers” sequel.

Thanks for this comment, L.D. Yes, I agree there are problems with the “not rape then-rape now” consideration. Here is how Scammell puts it in the section where he discusses the charge against Koestler: “The likeliest explanation is that behavior that wasn’t at the time seen as rape has since come to be regarded as such, and that it is necessary to keep both standards in mind.”

I don’t endorse that conclusion, but I hesitate to call Scammell out for it. If that’s necessary, I’ll leave it to those more expert in the sociology and discourse of misogyny.

The point I was trying to make in that paragraph was a much less complex one: re-visiting Scammell’s discussion of the rape charge against Koestler during the week of the Ford-Kavanaugh hearing was painful.

Anthony,

Agreed. Honestly, it was hard to think about anything last week that wasn’t somehow painful or dispiriting. There are men with current political careers and future political ambitions who feel “liberated” to openly traffic in the most vile, virulent misogyny (and racism) — no innuendo, no dog-whistle, just straight-up hate — because they are persuaded that they will not suffer any political consequences for it. And I fear that they’re right. It’s more painful than usual to be a woman in the world right now.