Editor's Note

Joshua A. Lynn is Assistant Professor of History at Eastern Kentucky University. He previously taught at UNC-Chapel Hill and Yale University. He teaches courses on the history of conservatism and is author of Preserving the White Man’s Republic: Jacksonian Democracy, Race, and the Transformation of American Conservatism (2019).

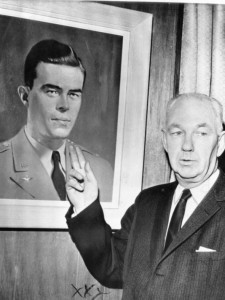

Robert Welch pointing to a painting of John Birch

It is easy to reduce a diverse group to a few uncharitable stereotypes by failing to seriously engage their ideas. That is what academic historians do to conservatives, Geoffrey Kabaservice recently claimed. But it is, in fact, what he just did to historians.

He takes issue with “liberal” academic historians, by which he means most academic historians, who chronicle the history of conservatism. He acknowledges the flurry of scholarship on this topic since the 1980s, as hundreds of books and articles have enhanced our understanding of conservatism in the American past. This body of work is impressive and discordant. Historians are not in agreement. Yet, citing a handful of unrepresentative books and some tweets, he concludes that academic historians are liberal propagandists who do not understand conservatism.

Conservatives shouldn’t dismiss the work of academic historians so fast, because they could learn much about themselves, the history of their ideas and movement, and why, even if they loathe him, they cannot disown Donald Trump, who is a product of the complex phenomenon that is American conservatism.

Historians are hardly in lockstep in researching and teaching the history of conservatism. Not all scholars agree that (1) conservatism is fundamentally bad or that (2) conservatism is bad because it is fundamentally racist. Historians’ flood of scholarship illustrates that conservatism has always been eclectic as a set of ideas and as a political force. Historians are not the ones guilty of reductionism or generalizations when it comes to conservatism.

Some conservatives downplay the Right’s internal diversity. Kabaservice, for instance, argues that “Liberalism and conservatism have conditioned each other throughout their collisions over the course of American history, the ever-evolving yin and yang of our collective political consciousness. While the present moment may be an exception, American liberals and conservatives have almost always shared the same goals of peace and prosperity, although the means proposed for reaching those goals have usually been very different.”

“Peace and prosperity” is a low common denominator for an American political consensus in which liberalism and conservatism are two sides of the same coin. Conservatives and liberals have often diverged not just on means but also on goals. To claim otherwise is to deny the diversity within American conservatism which academic historians have uncovered.

Arguing for a political consensus on fundamentals harks back to the mid-twentieth-century “consensus” scholarship of historians and political scientists who ignored ideological disagreement in the United States. According to them, conservatives were simply liberals, albeit ones who felt that liberal democracy needed to be conserved against the twentieth century’s totalitarian threats. Both conservatives and liberals, the argument went, esteem individual rights, free-market capitalism, and representative democracy.

A convergence between conservatives and liberals possesses historical validity, as many on the Right and Left do cherish liberal democracy. The irony that swathes of today’s conservatives are really old-fashioned liberals in the classical sense has long been noted by historians, political scientists, and conservatives themselves.

But what about those conservatives who have rejected individual rights, laissez-faire economics, and democracy, not to mention modernity and the Enlightenment? When the classical liberal F. A. Hayek, now an iconic figure on the Right, famously rejected the label “conservative,” it was because he did not want to be regarded as the fellow traveler of these illiberal conservatives.

Academic historians have not ignored illiberal conservatism. Neither should mainstream conservatives. Americans who have chafed at the constraints of liberal democracy are part of the American conservative tradition and have worked alongside others on the Right to roll back the progressive state.

Social organicism, localism, deference to tradition, and the humbling of the individual before hierarchy and divine order are hallmarks of traditionalist conservatism descended from Edmund Burke and updated for twentieth-century America by Russell Kirk. They have been used to advance some unsavory agendas. Illiberalism percolates aplenty in the United States, sometimes enabled by an intolerant Left, sometimes by an intolerant Right.

Many nineteenth-century conservatives, from the Federalists to the Whigs, made peace with representative democracy. Yet antebellum proslavery theorists railed against majoritarian democracy, yearning instead for a counterrevolution that would substitute racial hierarchy for egalitarianism and social organicism for liberal individualism. Their ideas drew from and contributed to the evolution of philosophical conservatism in the United States. Russell Kirk pointed to proslavery theorists as models in the 1950s, while more recently historian Eugene Genovese, after his shift from Marxism to traditionalist conservatism, celebrated John C. Calhoun’s philosophical conservatism.[1]

While some conservatives from the classical liberals of the Gilded Age forward have gleefully embraced modernity and capitalism, others such as Henry Adams, the Southern Agrarians, and more recently some paleo-conservatives have rejected what they perceive as selfish individualism and crass capitalism. Conservatives can be free market zealots, but they also have much to teach us about preserving values against the market’s dehumanizing encroachments.

Today many conservatives, especially libertarians, speak of natural rights and would insulate them from a tyrannical state. But other contemporary critics of liberalism like Patrick J. Deneen would empower local majorities of the likeminded to determine the rights of individuals according to local prejudice. Rolling back the federal state creates space for small-town tyranny.

In examining conservatism’s illiberal manifestations, academic historians stand accused of simplistically equating conservatism with white supremacy. Indeed, historians have long, and convincingly, emphasized an illiberal “white backlash” against the civil rights movement and a federal state slowly allying with racial minorities. In this rendering, populist rage and racist dog-whistles galvanized a conservative grassroots reaction from the 1960s down to Donald Trump and the alt-right.

Yet other scholars find different sources of inspiration for conservatism across US history and for the post-WWII New Right in particular. Scholarly debates, once again, demonstrate just how multifaceted conservatism has been. Looking beyond intellectuals and elites, historians have found a dizzying array of conservatives at the grassroots. Some mobilized against feminism and gay rights in support of “traditional” gender norms and conceptions of the family.[2] Business conservatives, meanwhile, shrewdly made free-market capitalism attractive to the masses by fusing libertarianism with populism.[3] Religious conservatives politicized fundamentalist Protestantism. Fear of communism at home and abroad inspired housewives to mobilize as political actors.[4] Conservatism took on different accents in the Rustbelt where blue-collar “white ethnics” became Reagan Democrats,[5] in the Sunbelt where suburbanites mixed capitalist acquisitiveness with evangelical piety,[6] and in the Deep South from which George Wallace exported his racist populism.[7]

American conservatism is not reducible to racism. But some varieties of conservatism are intertwined with it. Not all opponents of the liberal state are racists. Far from it. But most defenders of white supremacy have been antistatists out of fear that the federal government would muscle its way into local communities and mandate racial equality. Their animus toward the state and liberal reforms places them on the Right, often to the displeasure of other conservatives.

The designation of who is conservative has always been contested. Many on the Right battle over who is the real conservative. Today, Donald Trump wants to monopolize conservatism, while his detractors see him as its perversion. In 2012 we witnessed mild-mannered Mitt Romney goaded into designating himself “severely conservative” when accused of moderation by Republican primary opponents.

It is not historians who downplay the diversity of conservatives, but conservatives themselves when they question each other’s conservatism. Monopolizing the term is a claim to legitimacy. The conservatives who want to rehabilitate their movement by decrying Trump ignore the historical complexity of their own side of the political spectrum by denying him a place on it.

Historians are attuned to conservatism’s variations throughout American history. Calling attention to the manifestations that appear unseemly due to their racism and illiberalism should not be interpreted as claiming that all conservatives have been that way. Rather, historians follow the advice of Clinton Rossiter, an early scholar of conservatism, who wanted to “let the Conservatives speak for themselves.” It’s not historians’ fault that sometimes conservatives have said unpleasant things. Some conservatives have been illiberal, while others have championed human rights, democracy, and liberal internationalism. Academic historians should acknowledge this diversity.

So should conservatives. Mainstream conservatives proudly retell how William F. Buckley Jr. excised Robert Welch, founder of the far-right, conspiratorial John Birch Society, from their movement in the name of respectability. This ballyhooed moment is sanitized and self-serving history. The gatekeepers of conservative respectability banished Welch, but not his followers or his ideas, upon whom they relied for grassroots support. If liberals can be too critical as historians, conservatives can be too charitable.

Welch was useful for Buckley in the way that Trump is useful for establishment Republicans today. Conservatives like Senator Jeff Flake emulate Buckley.[8] They would sanitize today’s Right by treating the symptom but not the cause—excising the demagogue but not their own grassroots or the sensibilities that, although suddenly embarrassing, have long fermented on the Right.

Never Trump Conservatives and MAGA conservatives are all conservatives, each group representing aspects of conservatism that have long coexisted, not always peacefully. When conservatives cauterize themselves from their own history by only celebrating respectable intellectual gatekeepers like Buckley and electoral successes like Reagan, they engage in the reductionism and moralizing that “liberal” historians are accused of. Maybe it’s some conservatives who need to be better historians, because the historians themselves are doing a fine job.

Notes

[1]Eugene D. Genovese, The Southern Tradition: The Achievement and Limitations of an American Conservatism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

[2]Donald T. Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman’s Crusade (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005).

[3]Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009).

[4]Michelle Nickerson, Mothers of Conservatism: Women and the Postwar Right (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

[5]Thomas J. Sugrue and John D. Skrentny, “The White Ethnic Strategy,” in Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s, ed. Bruce J. Schulman and Julian E. Zelizer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 171-92.

[6]Lisa McGirr, Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[7]Dan T. Carter, The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics, 2nd ed. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

[8]Jeff Flake, Conscience of a Conservative: A Rejection of Destructive Politics and a Return to Principle (New York: Random House, 2017), 61-64.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’m not sure where you and Kabaservice disagree. You describe “the complex phenomenon that is American conservatism,” and K. at least notes “traditionalists, libertarians, paleo-conservatives and neo-conservatives, among any number of ideological splinter groups,” as well as “monumental divisions on the right.”

The difference is that you seem to want to write about “conservatism” generally in all its “diversity,” while K. wants to write about a “conservative movement” or a “conservative mainstream.” For him, there have been conservative gatekeepers who, despite any number of “moral blot[s],” can draw boundaries based on intelligible criteria, such as dismissing “conspiratorial fantasies” and the “political-media entertainment complex” in favor of “serious [intellectual] work,” and ideological purity in favor of Reaganesque “pragmatic dimension[s]” for the purpose of effective governance (etc.).

You are right if conservative gatekeepers have not been willing or able to draw boundaries based on intelligible criteria, so that there is no meaningful “conservative mainstream” distinct from “conservatism.” (You hint at this when you suggest that the banishment of Welch was not really a banishment and perhaps in bad faith.) K. is right if the conservative gatekeepers have been willing and able to draw such boundaries, so that there is a “mainstream” and “movement” distinct from “conservatism” simpliciter that would be of primary interest to political and intellectual historians.

Perhaps it is likely that you are both to some extent right. In other words, there is a distinction but not one as strong as K. would like. In that case, the disagreement may not be severe.

(All this is not to comment of some other aspects of the discussion on the blog, which I do not understand.) Thank you.

It is true that conservatism is a complex and varied movement and belief system; and, as you say, the (mostly) liberal historians have indeed featured many different strains conservatism in their recent books. My own study of Edmund Burke in America made this point not just about the postwar era, but with regard to U.S. political history since the Revolution. Making this necessary and valid observation (about the diversity of conservatives) can, however, unintentionally eclipse one of the most important characteristics of conservatism. Namely, that conservatism (or the Right) tends to be united less by the details of what its members believe, than by what they oppose. Conservatives of almost all stripes fear and contest the values and ideals of the Left: especially in politics, when push comes to shove (like on Election Day) they are on the same side. As William F. Buckley said in the 1950s: the incompatible camps of conservatism did not appear to be choking each other off, and that there seemed to be a “symbiosis” of the conflicted Right. This was thanks to its common enemy, the (then) supposedly hegemonic culture of liberalism.

Another example can be found in the antebellum period, when three prominent conservatives—each of a different variety—invoked the wisdom of Edmund Burke to stave off interference with Southern slavery. The first, Hubbard Winslow of Boston, personally opposed slavery, but he vigorously attacked abolitionists using Burke’s crusade against French revolutionary radicals as his ammunition. The second, William Harper of South Carolina, defended slavery and the Plantation Aristocracy, and he used Burke’s antirevolutionary arguments to support both. The third, Thomas Dew of Virginia, disagreed with Burke’s arguments against the French Revolution (the chief reason for Burke’s claim as the Father of Conservatism!); Dew just had a problem with extending liberty and equality to blacks. Therefore, he used Burke (who actually opposed slavery and the slave trade) to make a positive defense of slavery, while rejecting the possibility of attacking abolitionists as Jacobins. So whether the excuse was preserving the union, deference to the Constitution, devotion to the Southern way of life, economics (Dew also made that defense), or racism, the end result was (Right) pushback against (Left) antislavery forces.

I think is a really, really important point. It is not always pushback against racial equality — sometimes it is against women’s liberation, or class equality, and more often than not some combo of two or all three — but despite all this diversity, conservatives do, indeed, tend to unite around what they oppose, which whether along lines of race, gender, or class, is indeed always against some kind of liberation movement from below. They might say it’s noble or whatnot, but that doesn’t make that description inaccurate.

And isn’t that just what Corey Robin argues? But those who relentlessly attack him for this either insist, without explaining why, or simply leave it assumed that the diversity is much, much more important than the unity. Why? This can’t just be asserted and taken for granted as more important.

If someone wants to honestly make an argument for human hierarchy, liberals and the left will argue with them all day long but ok, we are arguing honestly. And there are a handful of conservatives who still do that. But when scholars who point out that this IS what is being defended — some kind of hierarchy — and what is being attacked IS some kind of liberation for those further down the social ladder, are called reductionist for it, I don’t see how this isn’t clearly seen for the denialism it is.

And finally, in order to criticize something as reductionist, you can’t simply point to diversity, then use the term, and say DONE!, case proved! Again, you have to show that this diversity *matters more* than the unity — *because that’s not a given.*

“sometimes enabled by an intolerant Left”

/eyeroll

//posts “So much for the tolerant Left” Nazi-punching cartoon