For those of us on a semester schedule, classes begin in less than a month. So now is the time to put together fall syllabi. Since I’m starting a new job at a new institution, it’s going to take me a little bit longer than it usually does to figure out how to structure my courses, so I already feel like I’m behind. (Welcome to academe!) This fall I’ll have three preps – U.S. History to 1865 (two sections) U.S. History since 1865 (one section), and an Honors College section of U.S. History since 1865. The regular lectures have enrollments that vary from 45 students to 70 students, depending on room size, while the Honors section is limited to 25 students. And I am my own TA (which is fine with me).

I need to come up with a range of exercises, homework assignments and assessments that are scalable for a range of class sizes and manageable on my end in terms of grading. And for the Honors section, I need to come up with assignments that do not load down students with more work, but that guide them to a qualitatively deeper engagement with the material.

For the first time, I am assigning The American Yawp as the survey text for all sections. So I will be writing some new reading quizzes for the survey. And for the regular sections of the survey, there will be one or two substantial primary sources assigned each week that will serve as the basis for required online discussions. (If anyone has a rubric / model guideline for discussion board assignments, please feel free to provide a link in the comments.) Exams will be take-home essay exams for all sections.

But what to do for the Honors section, that class of 25 students who will meet in a small room — perhaps even around a seminar table — in the residential Honors Hall at Tarleton State?

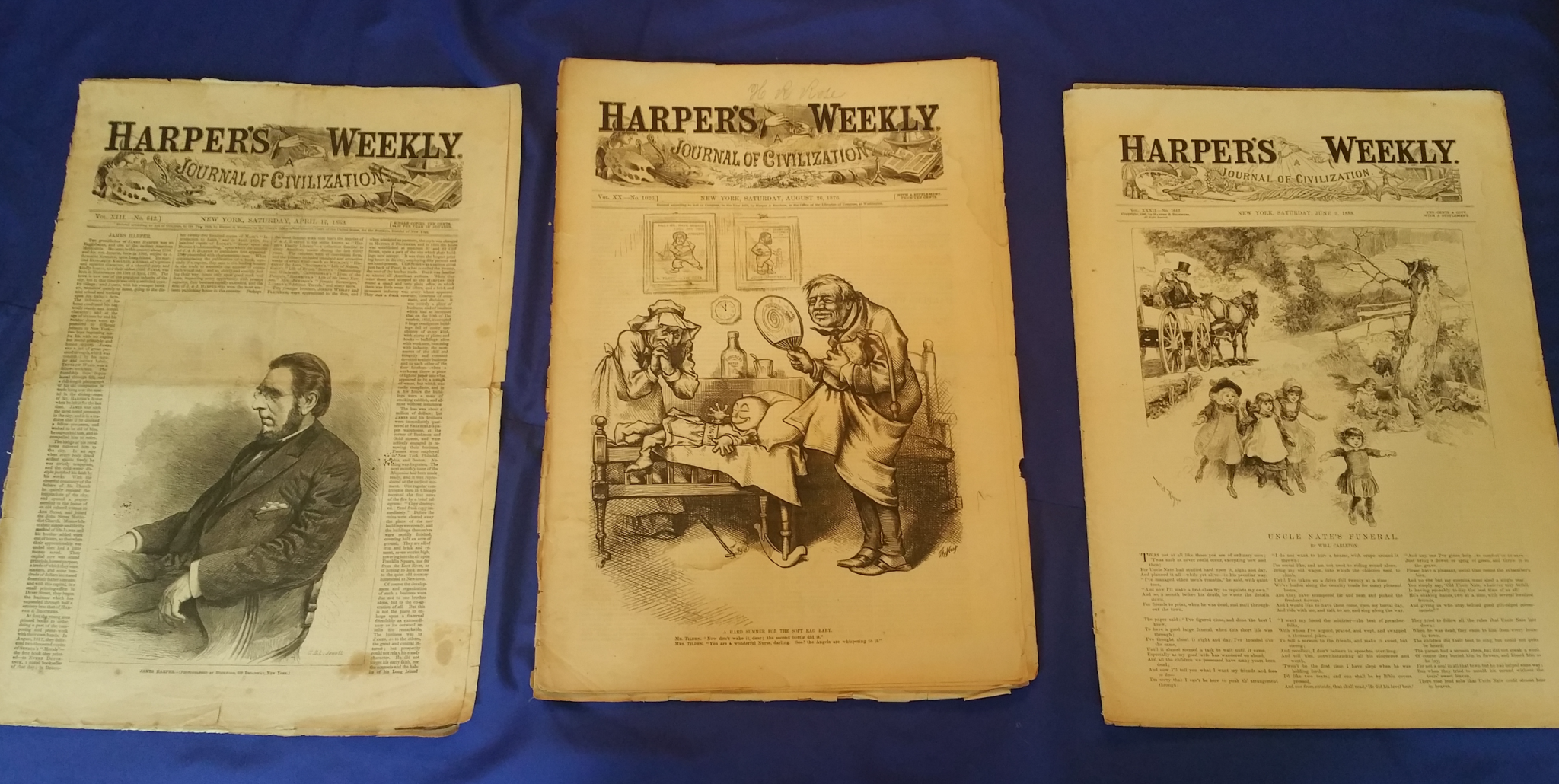

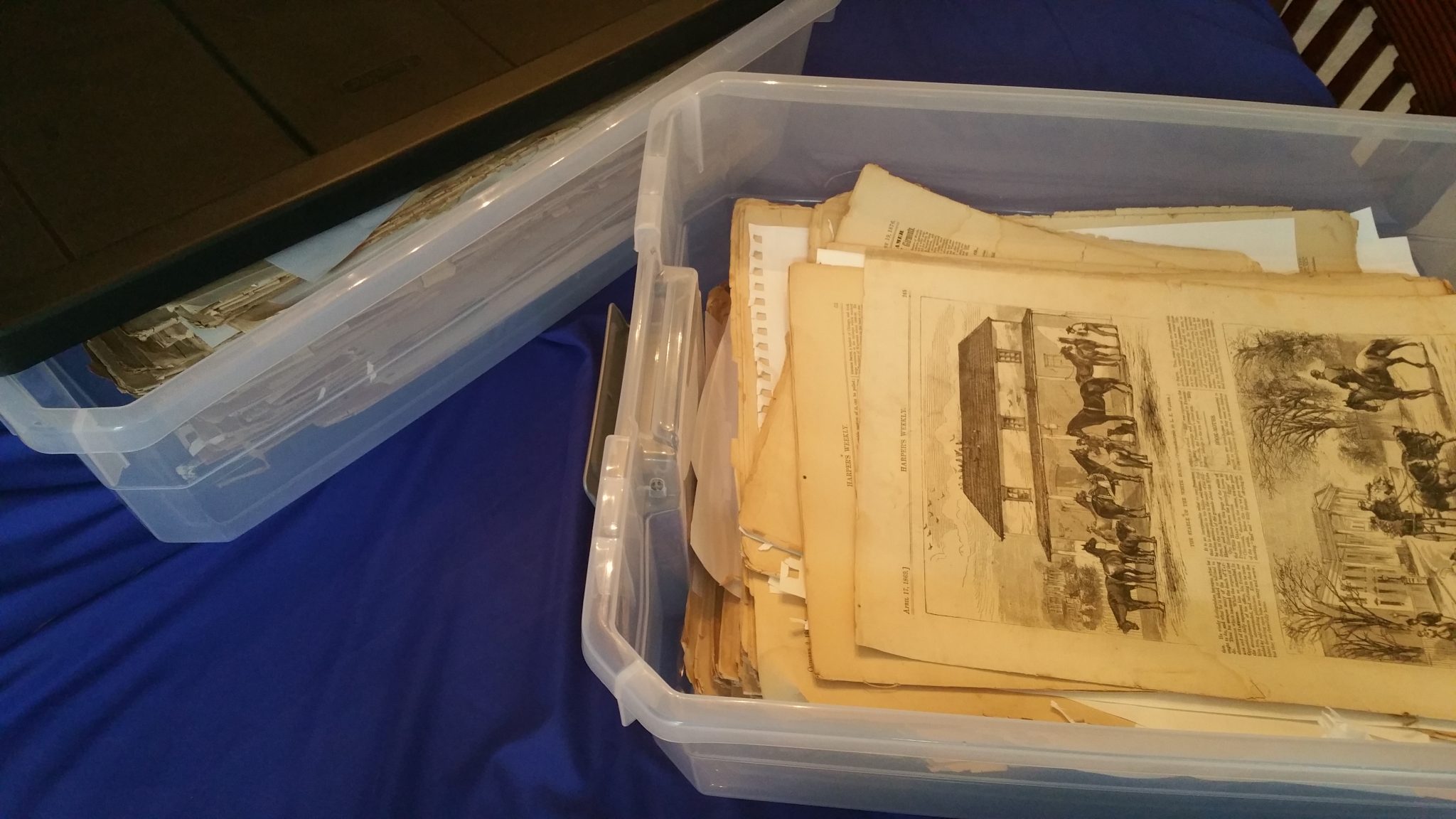

A seminar, of course, in the style of Herbert Baxter Adams. And I have just the thing to bring to the table to get us started this fall: a few hundred issues of Harper’s Weekly

dating from the 1860s to the 1880s.

I have my parents to thank for this trove of primary source material. They were tooling around somewhere in east Texas and stopped at an antique shop that had all these old copies of Harper’s. The shop owner wanted $10 a number for the magazine. My folks asked, “How much for all of them?” She asked for $1,000. My folks talked to me about it, and told me about their condition (tattered, water-damaged, but legible) I told them not to give more than $500, and that I’d pay them back if they’d buy them for me.

At the time, I had access to the HarpWeek database through the UT Dallas Library. But now these scattered and tattered copies of Harper’s are my only portal to that publication – Tarleton State does not (yet) subscribe to that database.

So here’s what I’m thinking of doing…

I generally divide my survey course into three periods – 1865-1914, 1914-1945, 1945-present. And I’m going to cover the same things in that first period that one covers in any U.S. history survey – Reconstruction, the war for the West, industrialization, urbanization, immigration, the New Woman and Manhood/Masculinity, Gilded Age / Progressive era politics. The usual.

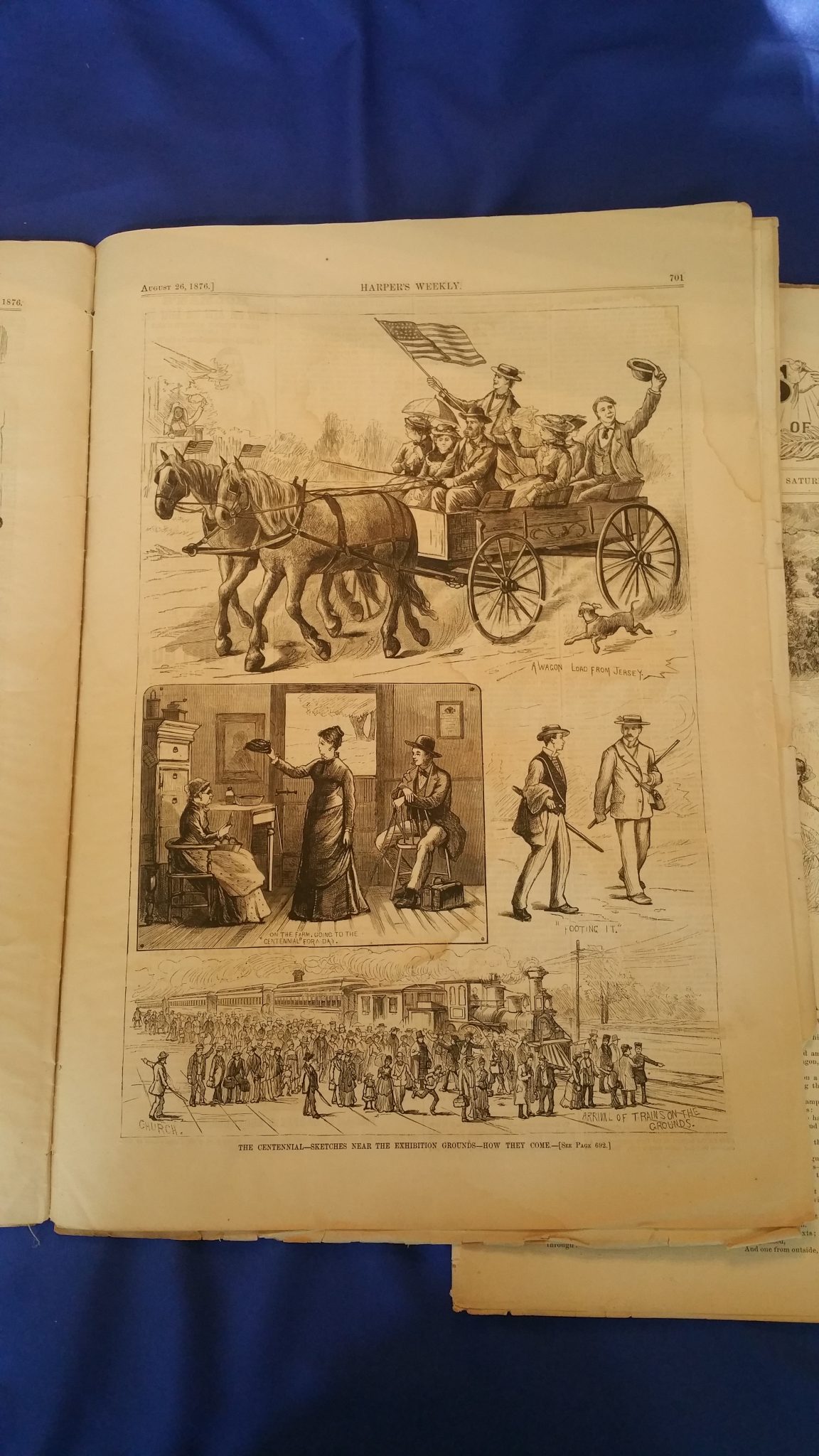

I will randomly assign each student in the class a particular number of Harper’s Weekly. I will bring those to class with me and perhaps even put them on reserve (!!!) at the Honors College office or at the library. What I’ll be asking students to do is to write a paper demonstrating how each of the themes we are covering (or perhaps a selection of three related themes) shows up in that single issue of Harper’s Weekly, and how the treatment of those themes in that particular issue adds to our understanding of U.S. history during this period.

Pretty fun, huh?

I can do something similar with LIFE magazine for the 1960s and 1970s – I think I have enough hard copies. But what I’d really like is a trove of large-circulation magazines from the Depression era, and another trove of large-circulation magazines from the 1940s-1950s. I will be looking on ebay to buy some back issues in bulk. However, if you have a packrat in your life – if you area packrat – and you have dusty old stacks of Redbookor McCall’s or TIMEfrom, oh, the 30s to the 60s, just sitting around, holler at me.

In lieu of magazines, I could also use newspapers. And of course I can always assign accessible numbers from Chronicling America or google’s trove of fully-digitized magazines.

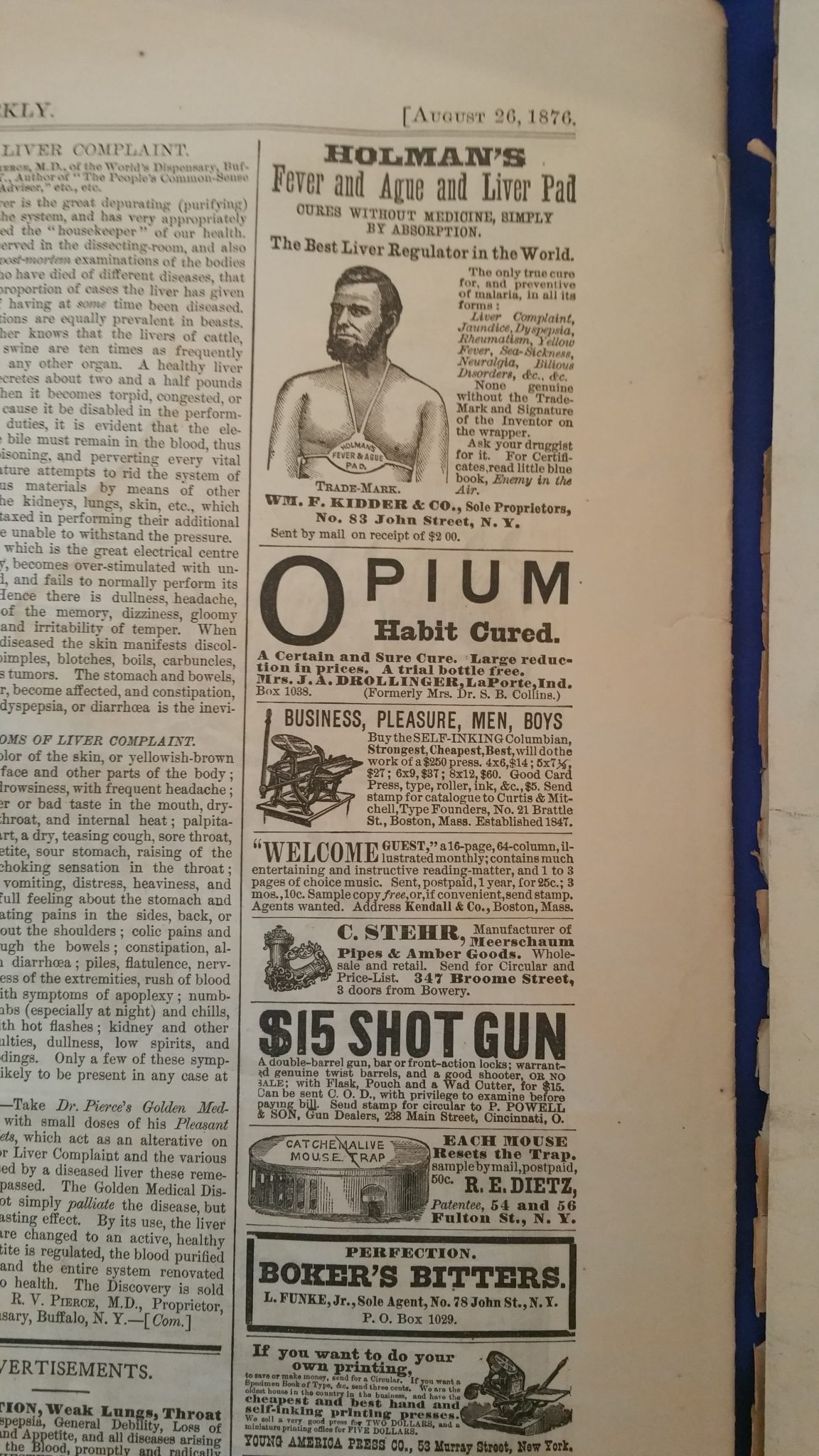

But there’s something very valuable about handling primary sources, and this gets down to our enduring (and unsolvable) debate about text v. context, material v. ideal, accidental v. essential. In terms of our disciplinary debate, I stand on somewhat shaky ground, insisting on the final insolubility of the nexus between an idea and its means of conveyance. That is, the bond between “an idea in the abstract” and “the material conditions of an idea’s creation/communication” inheres in both the idea and the thing. No ideas but in things, yes – but also, no things but in ideas. So, I hold that ideas are real (as opposed to epiphenomenal) and immanent (as opposed to transcendent).

But there’s something very valuable about handling primary sources, and this gets down to our enduring (and unsolvable) debate about text v. context, material v. ideal, accidental v. essential. In terms of our disciplinary debate, I stand on somewhat shaky ground, insisting on the final insolubility of the nexus between an idea and its means of conveyance. That is, the bond between “an idea in the abstract” and “the material conditions of an idea’s creation/communication” inheres in both the idea and the thing. No ideas but in things, yes – but also, no things but in ideas. So, I hold that ideas are real (as opposed to epiphenomenal) and immanent (as opposed to transcendent).

Am I going to lay that debate on my history 1302 honors students this fall? Not all at once, certainly. What I am going to do, I hope, is lay before them some tangible remnant of a past, a past that pops with life, a past they can almost touch by handling these material artifacts, these fixed and fragile records of ideas on the move.

That’s the plan anyhow. I would welcome any and all suggestions. I should have a Tarleton State email account after August 1, and my UT Dallas email account will vanish, I am told, on August 4. (Don’t worry; I’ve saved my receipts.) So the best place to offer suggestions or resources or critiques for now is here in the comments on this post.

Thanks for reading, and thanks in advance for your help and advice.

10 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is such a terrific approach! I *wish* I had a trove of periodicals, but instead I offer links to several open-access digital resources that may be of interest:

‘The Colored American Magazine,’ 1900-1909 http://coloredamerican.org/?page_id=23

The Internet Archive’s ‘Magazine Rack’: https://archive.org/details/magazine_rack?&sort=-downloads&page=3

Cornell University Library’s ‘Making of America Collection’ http://collections.library.cornell.edu/moa_new/browse.html

I’ve taught a course based on primiary source materials that the students had to find themselves. Rather than ask them to discuss how the sources fit into the familiar narratives, I asked them to do the opposite – to discuss to what extent the primary sources modified the familiar stories. They always did.

Yes, I taught my upper div seminar last spring that way. I was really pleased with the sources students found and what they did with them.

I am gutted that I’ll lose access to HarpWeek after August 4, but hopefully I can make a case for the importance of this resource for U.S. history. I have selected the 25 numbers I’ll be assigning to my students.

I like assigning sources for some work because in these exercises I want my students to glean what they can from the materials available to them — one important skill historians develop. You go into an archive, hoping you’ll find X, spend all day there, don’t find X, but do find other stuff that you realize you can use.

Later in the semester, I’ll let them pick their own number from one of the digitized runs in google, but for now, I want to walk them through not only making do with what the archive holds, but also carefully handling archival material. It’s going to be an interesting semester for me, and hopefully for them too.

Sounds great. This may be the last generation to physically handle archival sources…

Thanks so much for this post!

In the American Studies seminar that I’ve used to produce The Berkeley Revolution (revolution.berkeley.edu), I’ve started with an ‘Annotation Assignment” that asks them repeatedly to make a connection between a detail of the document they’ve chosen and its significance — my way of getting students to slow down, read closely, and think meticulously. The assignment doesn’t ask them to sum up the various annotations into an essay, but rather just asks them to pay attention to details and to generate questions around the document. (Later on, they’ll have to write a more synthetic essay.)

I’ve pasted part of the assignment below.

=====

ANNOTATION ASSIGNMENT

What You’re Asked to Do

Choose a primary source document from the rough period investigated by this class (say, 1966 to 1980) — a ‘juicy’ document that speaks to some historical complexity and/or to some complexity in the person or people who created the document. Keeping the chapter on “Texts” from American Studies: A User’s Guide in mind, examine the document with meticulous attention to its details. You are asked to make between six and ten annotations of the document. In each case, your annotation should do three things: (1) refer to, or label, a specific section or aspect of the document and give it a number; (2) offer a description of that aspect of the document (answering the question ‘what do you see’?); and (3) enlarge upon the significance of that aspect of the document.

For instance, a few classes ago we looked at Nacio Jan Brown’s photograph of Telegraph Avenue from Rag Theater. You might (1) label the slant of the street that the perspective of the photograph gives us (“Annotation #1: A slanted street”); (2) describe how the figures in the photograph come to us at that slant (“Description: As viewers we are posed directly in front of the address of the ‘Rag Theatre’ store, but the sidewalk is at around a 15% angle to the bottom edge of the photograph. This angle lends a slight tilt to the figures in the photograph, with the dancing girl on the sidewalk on the left appearing to be around the same distance from the viewer as the young woman who sits in the gutter on the right.”); and then (3) interpret, over a few sentences, what the larger effect of this slant might be (“Significance: This photograph gives us a world that feels off-kilter, no matter how many aspects of balance there are within the composition, ….”) This would comprise one of your 6-10 annotations. Each annotation should have a number, a ‘description’ section, and a ‘significance’ section.

Lastly, as a final ‘annotation’ (in addition to your 6-10), you are asked to pose at least three questions that are generated from your document and point beyond it. For instance, from the Rag Theater document, you might ask: “What sorts of clothes did the shop ‘Rag Theatre’ sell?” “How many young people were living on the streets of Berkeley when this photograph was taken?”, “What percentage of Cal students, and what percentage of Berkeley residents, at the time were African-American?”, “Did older Berkeleyans avoid Telegraph Avenue?” and many more.

What a fantastic assignment. Thanks for sharing this (and the URL for your project — nice!)

A big bunch of Harper’s Weekly are fully available to all at HathiTrust Library https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000061498/Home

No Life, McCalls, or Time, but I do have 2 silverware boxes full of Boy’s Life scouting magazine in the garage (I bought them at an auction with some other things and despite my best intentions never have gotten around to using them for research). If they’re of interest I can check dates.

Ethan, that would be *great.* I will ping you. Thanks!

Scott, after finishing out my syllabus and looking over the reading load / writing load / semester pacing, etc., I’ve decided I’m going to do a modified version of your annotation assignment rather than formal / polished papers. Thanks again for sharing it here!