Editor's Note

For nearly two decades, I’ve taught an undergraduate Honors Course at the University of Oklahoma built around the readings in Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition. As part of LD Burnett’s series of posts rereading Hollinger & Capper, I’m doing a series of posts exploring what it’s like to teach the volumes in an undergraduate, honors setting. In my first post, I said a few general things about Perspectives on the American Experience: American Social Thought, the course (or actually courses) in which I use The American Intellectual Tradition. When I began this course, The American Intellectual Tradition was in its 3rd edition. Unless otherwise noted, I’ll be blogging about the most recent edition of the books, the 7th. In this fourth post in my series, I discuss teaching Volume I, Part Three, entitled “Protestant Awakening and Democratic Order.” For more on Volume I, Part Three, see LD’s post from earlier this week. I’ll be blogging about a new section every two weeks as LD works her way through the book. I am not attempting to make these posts a comprehensive description of what I do with Hollinger & Capper in the classroom. Instead, I will be highlighting an aspect of my approach to each section. Please feel free to use the discussion thread for more general comments or questions about teaching this particular part of The American Intellectual Tradition.

Volume I, Part Three of Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition includes readings that span the period from 1819 to 1851. But the bulk of the readings in this section, which is entitled “Protestant Awakening and Democratic Order,” come from the 1830s and 1840s. They focus on various forms of early 19th-century Protestantism, the Second Great Awakening, social reform, and ideas associated with the two great political parties of this period the Democrats, represented here by George Bancroft, and the Whigs, whose ideas on trade and cross-class solidarity Henry Carey embodies.[1]

Volume I, Part Three of Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition includes readings that span the period from 1819 to 1851. But the bulk of the readings in this section, which is entitled “Protestant Awakening and Democratic Order,” come from the 1830s and 1840s. They focus on various forms of early 19th-century Protestantism, the Second Great Awakening, social reform, and ideas associated with the two great political parties of this period the Democrats, represented here by George Bancroft, and the Whigs, whose ideas on trade and cross-class solidarity Henry Carey embodies.[1]

I do a lot in the classroom with these very rich readings, but having just spent four week each on Puritanism (in Part One) and the republican enlightenment (in Part Two), my students are primed to notice the many ways in which the enlightenment and the political culture of the early republic inflect American Protestantism and the ways that those emergent forms of Protestantism, in turn, shape changes in early nineteenth-century American political culture.

Indeed, throughout Part Three, authors we read even suggest that constitutional democracy and Protestant Christianity are, in a sense, identical.

The Unitarian William Ellery Channing, writing in 1819, does this in the course of describing how Unitarians read the Bible:

We reason about the Bible precisely as civilians do about the constitution under which we live; who, you know, are accustomed to limit one provision of that venerable instrument by others, and to fix the precise imports of its parts by, by inquiring into its general spirit, into the intentions of its authors, and into the prevalent feelings, impressions, and circumstances of the time when it was framed. (242)

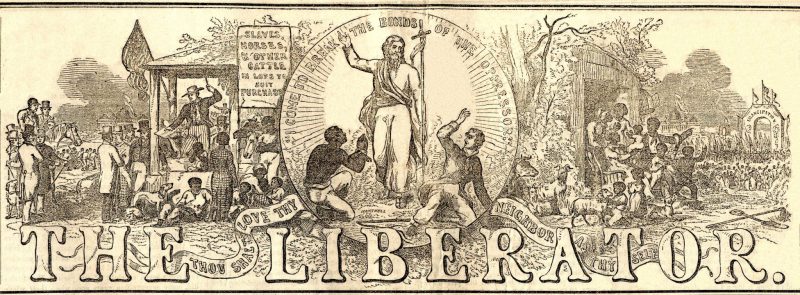

William Lloyd Garrison, whose brand of religion was quite different from Channing’s, suggests, in 1832, that the Declaration of Independence and the New Testament provide equivalent paths to the abolition of slavery:

As long as there remains among us a single copy of the Declaration of Independence or the New Testament, I will not despair of the social and political elevation of my sable countrymen. (294)

And Catharine Beecher, whose political vision was much more conservative than Garrison’s, similar suggests, in 1841, that the Bible and the Declaration of Independence are equivalent guides to the good society:

The great maxim, which is the basis of all our civil and political institutions, is that “all men are created equal,” and that they are equally entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

But it can readily be seen, that this is only another mode of expressing the fundamental principle which the Great Ruler of the Universe has established, as the law of His eternal government. “Thou shalt love they neighbor as thyself;” and “Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them,” are the Scripture forms, by which the Supreme Lawgiver requires that each individual of our race shall regard the happiness of others, as of the same value as his own; and which forbid any institution, in private or civil life, which secures advantage to one class, by sacrificing the interests of another.

The principles of democracy, then, are identical with the principles of Christianity. (311)

These three texts, and others we read in this section of The American Intellectual Tradition, highlight the ways in which Americans in the 19th century often treated the founding documents as almost sacred texts, whose form and content was like that of the Bible. But the readings in Part Three also make clear that, far from indicating an easy religious or political consensus, the commonly held notion that the Bible and the Declaration (or the Constitution) were essentially alike shaped a rhetorical space for political and religious disagreement.

In “The Laboring Classes” (1840), Orestes Brownson puts forward a strikingly radical vision, unlike anything else we read in this volume. Brownson argues that wage labor is worse than slavery, that hereditary property should be abolished, and that, throughout history, most of the ills of the world flowed from what he calls “priesthood.”[2] But though his political views are highly unusual, Brownson, like Channing, Garrison, and Beecher, suggests that his explicitly religious vision is nothing more nor less than the founding idea of his country. Sounding a bit like the prophet Isaiah (“Is not this the fast that I have chosen?…”), Brownson writes:

What in one word is this American system? Is it not the abolition of all artificial distinctions, all social advantages founded on birth or any other accident, and leaving every man to stand on his own feet, for precisely what God and nature have made him? (339)

I spend less time in the classroom with Part Three than I do with Part One or Part Two. This reflects the fact that I don’t supplement our readings in this section with additional works, as I do when teaching the first two parts of the book. Part Three divides very nicely into two weeks. Its first half consists of more theological readings: William Ellery Channing, Nathaniel William Taylor, Charles Grandison Finney, and John Humphrey Noyes. Its second half focuses on more reform-oriented and political authors: William Lloyd Garrison, Sarah Grimké, George Bancroft, Orestes Brownson, Catharine Beecher, and Henry C. Carey. In between these two weeks, Spring Break usually falls, which has the benefit of giving the students more time with these texts…assuming, that is, they want to spend Spring Break with George Bancroft and company.

Notes

[1] For a complete list of the readings in Volume I, Part Three, see L.D. Burnett’s post from earlier this week.

[2] Brownson, in 1840, wanted to build the Kingdom of God on Earth, but he argued that the State, not the Church, should be the foundation of the holy kingdom. A few years later, he would largely abandon this vision and convert to Catholicism.

0