Editor's Note

For nearly two decades, I’ve taught an undergraduate Honors Course at the University of Oklahoma built around the readings in Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition. As part of LD Burnett’s series of posts rereading Hollinger & Capper, I’m doing a series of posts exploring what it’s like to teach the volumes in an undergraduate, honors setting. In my first post, I said a few general things about Perspectives on the American Experience: American Social Thought, the course (or actually courses) in which I use The American Intellectual Tradition. Last week, I discussed teaching Volume I, Part One, “The Puritan Vision Altered.” When I began this course, The American Intellectual Tradition was in its 3rd edition. Unless otherwise noted, I’ll be blogging about the most recent edition of the books, the 7th. In this third post in my series, I discuss teaching Volume I, Part Two, entitled “Republican Enlightenment.” For more on Volume I, Part Two, see LD’s post from earlier this week. I’ll be blogging about a new section every two weeks as LD works her way through the book.

“Democracies are built out of language. To succeed as citizens we need to understand this fundamental political fact.”

– Danielle Allen, Our Declaration[1]

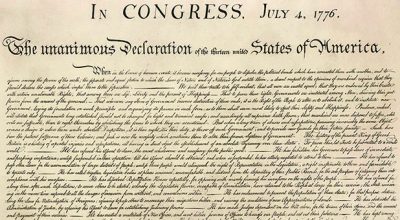

Volume I, Part Two of Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition contains what is probably the single most familiar document for my students in the entire collection: the Declaration of Independence. For years, its very familiarity made it oddly difficult to teach. Though one of the shortest documents in the volume, about two-thirds of the Declaration consists of its long list of “Facts…submitted to a candid world” that I found difficult to say much about in the context of a course like mine. Given the richness of the other materials in Part Two, which also happened to be less familiar to my students, I spent very little time on the Declaration during the earlier versions of my course in which we raced through both volumes of The American Intellectual Tradition in one semester. It was important that we read the Declaration and took note of it, especially as its ideas would prove crucial in Volume I, Part Five (“The Quest for Union and Renewal”), in which Southerners like John C. Calhoun and George Fitzhugh go out of their way to deny its premises, while Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass rest their arguments about the core values of the Union on its claims. But I always felt bad that I wasn’t giving the Declaration its due.

Then, in the Fall of 2015, I led an Honors Reading Group on Danielle Allen’s Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality, which had been published to much acclaim about a year earlier.[2] Although Allen, a MacArthur Fellow, political theorist, and classicist, discusses some of the history of the Declaration’s creation – she is very insistent on its being the work of many hands – she is most concerned with treating it as a living text. She sees it as making an argument about the importance of political equality to liberty, an idea that she thinks has been drowned out, in popular political rhetoric, by the notion that liberty and equality are opposing values, to the detriment of equality. As an African American woman, Allen is also especially acute about the conundrum of the Declaration’s universal language proclaiming the birth of a nation that protected slavery, provided women with few political rights, and excluded Native Americans from its self-understanding. Allen made the Declaration newly interesting to me and the students in my reading group in many ways.

However, that same semester, before I could really think about how Allen might lead me to teach the Declaration differently, I also made the decision to split American Social Thought in two when I next taught it the following spring.[3]

Suddenly I found myself with space for additional readings. In addition to adding Michael Winship’s book on Anne Hutchinson to my syllabus, I decided to add Danielle Allen’s book. The Declaration would go from being the most neglected document in Part Two in my course to becoming the focus of an entire week of the class.

After spending a week on the excerpts from Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography, John Adams’s A Dissertation on the Canon and the Feudal Law (1765), and the selection from Tom Paine’s Common Sense

(1776), our second week studying Volume I, Part Two of Hollinger & Capper is now devoted to the Declaration and Our Declaration. Allen provides students with a model of how to read a text closely. And she also shows them that one can make a strong argument of 21st-century significance about an 18th-century text.

Allen fits especially well in the middle of this unit of my course because I’d always taught this material with a bit more of an eye to its future than to its past. I’m of course interested in the origins of the ideas of the Declaration…and for that matter the ideological origins of the Revolution itself. But, in this course, I’ve always tended to focus on anticipating the way these ideas play out in the ensuing decades of American intellectual history and on asking my students to compare their own, 21st-centurty understandings of the issues raised in Part Two to those of the authors that we read.

After our Declaration week, we spend a week on the readings related to the framing of the Constitution – Hamilton’s speech at the Constitutional Convention, the selections from the Antifederalist essays of “Brutus,” and James Madison’s Federalist 10 and 51

.

Then we conclude, in our fourth and final week on Part Two, with the remaining readings in it: Judith Sargent Murray’s “On the Equality of the Sexes” (1790), selections from Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia

(1787), the selection from Samuel Stanhope Smith’s An Essay on the Causes of the Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species (1810), and the various letters by Jefferson and Adams.[4] On my syllabus, I label this last set of readings “Gender, Class and Race in the New Republic,” which doesn’t quite capture all that’s going on in these texts, but does identify a lot of the important strains in them.

Using Allen as a pivot for the readings in Part Two underscores what I take to be some of the most important issues raised by this section of The American Intellectual Tradition: What is required to make a government – and especially a republican government – work? What should the relationship be between the people and their representatives? How should the government be structured to produce policies that favor the common good rather than some corrupt interest? Underlying these questions are disagreements among the authors about human nature. And these, in turn, are related to Murray’s arguments for women’s rights and Jefferson’s and Smith’s competing accounts of racial difference.

As I write these posts, I realize that I am only going to be scratching the surface of what I do in the classroom with Hollinger & Capper. This is unsurprising, I suppose. It’s hard to summarize four weeks of teaching in fewer than two-thousand words. So please feel free to use the comment section to discuss any issues about teaching Volume One, Part Two, whether or not I happen to have already raised them in this post.

Notes

[1] The title of this post is shamelessly borrowed from last October’s joint issue of the William and Mary Quarterly and the Journal of the Early Republic entitled “Writing To and From the Revolution.”

[2] Honors Reading Groups were the signature program introduced by my recently retired Dean, David Ray. Students receive books for free and read about thirty-to-fifty pages a week. Some reading groups are student led; others are led by staff or faculty. I often use them as an occasion to read books that I might not otherwise get to, but that sound as if they’d profitably be read along with a group of students. Our Declaration, which starts with Allen’s description of reading the Declaration with two very different groups of University of Chicago students and which concerns, among other things, reading itself, seemed like the perfect sort of book for an Honors Reading Group. And it was.

[3] For more on this decision see my first post on Hollinger & Capper.

[4] The addition of the Smith reading to the 7th Edition (2016) of AIT is the only major change to Part Two since at least the 4th Edition (2001) (though an extra passage from Paine’s Common Sense was also added. Smith provides a nice counterbalance to Jefferson’s racism, though my students tend to find Smith’s notion that, given the right environment, black people will literally become white, to be pretty problematic, too. But reading Smith makes it impossible for students to simply conclude that Jefferson believed as he did because “everyone” had those beliefs in the eighteenth century. These readings also feature one of the more puzzling (and long-standing) editorial decisions in AIT: printing John Adams letter to Thomas Jefferson of November 15, 1813 (pp. 191-195) several pages before Jefferson’s letter to Adams of October 28, 1813 (pp. 209-212) to which it responds.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Excellent post, Ben, thanks. Readers may want to check out a related resource, the Declaration Resources Project (https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu). While John Adams’ “Dissertation” is significant, I’d recommend his “Thoughts on Government” as a clear blueprint of his political thought, and it’s available to read free as a digital edition here: https://www.masshist.org/publications/apde2/view?&id=PJA04dg2.

Ben–

Thanks for this. I, like you, have been teaching this for many years, but I have always made the Declaration and Madison’s #10 and #51 the central texts in the section, mostly because they can be used to bounce off the other texts. I ask students how they might square Jefferson’s statement of human equality in the Declaration with his statements in Notes on the State of Virginia and his letter to Adams on “natural aristocracy” (as well as his “naturalization” of Christianity in the letter to Thomas Law). Understanding the commitment to equality as essentially a critique of aristocratic hierarchy and heredity (rather than an expression of racial egalitarianism), allows students to see that the invention of scientific racism could be part and parcel of an Enlightened sensibility–which I hope gives students pause about what assumptions “Enlightenment” carries with it. I usually play Madison off of Paine (as well as Brutus and Hamilton), because Paine’s critique of “mixed government” and distant representation as obfuscations of republican principles can be so clearly juxtaposed to Madison’s commitment to an architecture of checks and balances. I find, in fact, that this section of H&C is one of the most intellectually cohesive of all those in either volume. The Adams, Murray, and Smith readings all fit within the central ideological conceptions outlined in Jefferson and Madison, and Franklin’s autobiography provides an effective entryway from the Puritanism of the previous section.

I may use Danielle Allen’s book in a later iteration of my intellectual history class. One of the things I find interesting about it is her commitment to a “plain” reading of the text, which requires little background knowledge, and thus puts her at odds with some of the central tenets of intellectual history. That is, she takes her audience through the text sentence by sentence, with a notion that a student with no intellectual background can grasp the meaning of the text through common sense and careful consideration of language. But, unlike historians who might want to ask what early modern thinkers and schools meant by some of the central conceptions in the first part of the Declaration (“Nature’s God,” “self-evident truths,” “pursuit of happiness,” etc.), her commitment to accessibility to a modern audience leads her to downplay the historical “otherness” of the text. I think it’s a great book, but it highlights some of the ways in which political theorists and intellectual historians differ from one another.

This has nothing to do with teaching H&C, but since J. Adams comes up in the post and comments and there seems to be quite a lot of interest in Arendt at this blog, I’ll mention one of the quotes from Adams (it’s from “Discourses on Davila”) that she uses in On Revolution, about the invisibility of “the poor man” who “feels himself out of the sight of others…. He is not disapproved, censured, or reproached; he is only not seen. To be wholly overlooked, and to know it, is intolerable.”

This passage, in which I suspect (?) Adams sounds somewhat more sympathetic to the plight of the destitute than perhaps he actually was, made a sufficient impact on two students of economic development in (what used to be called) the Third World that they used it as an epigraph: see E. Owens and R. Shaw, Development Reconsidered, Lexington Books, 1972, p. 1. (In fact it’s from here, not from Arendt, that I’ve taken the quote, but I know Arendt uses it and I believe it’s from reading her that Owens got it.)

Louis, I would defer to Sara on Adams’s opinion towards the destitute. But I will say (as I did say in one of my posts in this series, though hell if I can remember which one at this late date in the semester) that John Adams’s views on “democracy” get a much-deserved re-reading in Kloppenberg. Of course he was and is a foil for Jefferson, but the idea that he was a crypto-monarchist ready to reinstitute aristocracy in the US may have more to do with anti-Federalist polemic than with Adams’s ideas (this last point made nicely by Marcus Daniel in Scandal and Civility).

Of course there’s no defending the Alien and Sedition Acts or other such foolishness. That is, I think, a separate problem, though there’s probably a through-line of unease around restless rabble of one kind or another.

Thanks, will reply later properly. But I happen to be downtown at the moment, having just heard a lecture by a historian, and am looking down Pa. Ave on a gorgeous spring late aft with a picture postcard view of the Capitol. Talk about an apt setting for reading this thread!

Ok, slightly more substantively: I have to defer to your and/or Sara’s and/or Kloppenberg’s take on Adams, and I probably should have omitted that aside. Anyway, it’s a pretty good quotation, irrespective of how representative of his views it was.