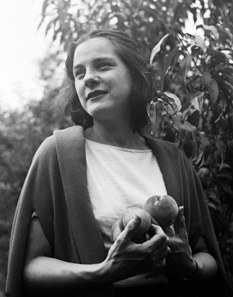

Mary McCarthy. Image courtesy of The New Yorker

Is it fair to say that (U.S.) intellectual historians have seldom paid much attention to the “novel of ideas?” Fiction—not to mention poetry—exists outside the universe of the Hollinger/Capper anthology.[1] Or rather it exists only as a kind of reference, in essays like Melville’s “Hawthorne and His Mosses” and James Baldwin’s “Everyone’s Protest Novel.” Few intellectual historians deal directly and naturally with fiction as if it contained the same kind of raw material—words and notions, images and visions—as, say, a sermon.

I’m not pointing this out to dissent, necessarily; in some ways, I think the lack of interest means that there is a salutary lack of tradition to contend with—a problem that our colleagues in English departments and even American Studies departments still can’t shrug off, lo these many years after the canon wars commenced. Where the “novel of ideas” may, for an English prof, convey a very specific image and a constricting set of names and exemplars, for intellectual historians the category is rather empty, like a mansion built but never occupied.

That emptiness is promising at a time when more attention is rightly and belatedly being paid to the question of whose story gets to be heard. Rebecca Solnit’s recent “On the Myth of a ‘Real America’” is right now foremost in my mind, but this is a question that recurs time and again as writers grapple with the meaning of the #MeToo and #OscarsSoWhite movements in Hollywood storytelling and as journalism reckons with the way that sexual harassment and implicit bias has shaped not only journalists’ workplaces, but their stories as well. As Solnit writes, “one of the battles of our time is about who the story is about, who matters and who decides.”

In many ways, I think that we at this blog and many other intellectual historians—and historians in general—have been entrenched for some time on the battlefield to which Solnit refers: the questions of “who the story is about, who matters and who decides” have been the daily portion of our work, the soul of our strivings. Intellectual historians certainly have no corner on those questions—and perhaps nothing truly novel to contribute.

But in addition to those three questions, one of the key dimensions in this battle is “whose taste is to be satisfied?” And here is where I wonder if intellectual historians do have a kind of occupational advantage.

An essay like this, by UK don Sarah Churchwell, describes very well the conditions which obtain in world of letters. If the Age of the Great Male Novelists (Roth, Mailer, Bellow, Updike…) is at an end, the question of how to clean up their toxic masculinity will consume a great deal of literary scholars’ and critics’ energies for the foreseeable future. Does one still write about them? How is one to write a history of postwar literature without them?

But an even thornier problem exists within English departments and among literary critics, I think: the Great Male Novelists shaped the tastes of a couple of generations of literary scholars. Bellow, Roth, & Co. were the standards of muscularly intellectual writing: if Rabbit, Run was not a novel of ideas, it was a novel written by a very smart man. The braininess of novelists and the intellectual quotient of novels ever since the 1950s has been measured by the yardstick of these men—at least for those who make the rating of such things their business, that is, literary scholars, literary critics, and novelists themselves.

To put the matter plainly: I think it is going to be very difficult for people who have primarily studied literature as their main subject to extricate themselves from the legacy of that long disciplinary embrace with the Great Male Novelists. There is a kind of inertia built in to all aspects of academia, and that is especially true here.

But that may not be true of intellectual historians: there may be an opportunity here—precisely because there is so little writing by intellectual historians on fiction—to do very interesting work on the intellectual (as opposed to the purely aesthetic or formal) content of the novel. We can define the novel of ideas not according to an inherited standard of, say, Augie March or White Noise, but according to standards we can more actively and conscientiously define. There is an opportunity, I think, to bring a freshness and inclusivity to the study of the novel.

So, if you’ve made it this far, I’d like to ask you—especially with summer on the horizon—what novels will you as intellectual historians (inside or outside of academia) be reading? Some of my own suggestions are in the comments.

30 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks so much for this post Andy. I like this idea that intellectual historians doing novels are relatively unencumbered by what people in literary studies or American Studies do. I wonder if it would be helpful to think about whether some groundwork needs to be done on this issue of the “intellectual (as opposed to the purely aesthetic or formal) content of the novel”? That is, what precisely do intellectual historians do when reading novels? How is it different from what literary scholars do? Of course, there’s historical context for the writer and for the novel itself, but I read you to mean something deeper than that here, about how intellectual historians actually read a given text. (After all, we’ve seen you do a mighty nice job of it here on this blog on occasion.)

I’ve been thinking for a while now about how to use a reading of a novel to better explore a problem in political thought in a historically-situated way. So rather than saying, for example, “Alice Walker was at this point in her life when she wrote _Meridian_,” or :”_Meridian_ is part of a group of post-civil rights era novels concerned with x, y, or z,” (One is Walker’s biography, the other is Walker’s novel as indicator of cultural trends), I wonder what it would mean to actually read the text itself as a way to conceptualize and theorize a historically situated problem about, for example, the relationship between politics and love.

In this way, scenes/scenarios and characters in novels help intellectual historians better imagine a particular historical problem, and more importantly can travel some in time, either backward or forward. Arendt did this kind of thing with Billy Budd in _On Revolution_, but not exactly. So I’m wondering whether one way to think about this might be to look at how Arendt read fiction, or how, say Stanley Cavell or Cornel West read fiction and so on.

Maybe we can blur all three genres, checking out philosophers reading novels to figure out a way to better do intellectual history, to give ourselves ways to talk about doing ideas in context. From there, we might be better able to get at the freshness and inclusivity you’re describing, because the novelist in question is not there only to tick some box for the sake of proper coverage, etc., but to actually contribute to the theorizing and conceptualizing of the historical subject matter itself. In pragmatic terms, we can then make a pretty compelling case for why the Bellow/Roth/Mailer/Updike sorts don’t help us explore the kinds of questions we mean to answer.

Peter,

Thanks so much for these questions! I think that how we might fill that phrase “intellectual (as opposed to the purely aesthetic or formal) content of the novel” is absolutely the essential question, and probably it is best filled through dialogue, and perhaps even through practice.

I suppose I was thinking of the difference between intellectual historians and literary scholars as much in terms of what intellectual historians are not likely to do with a text as what they are.

I think there is a set of disciplinary debates, scholarly conventions and even epistemological priors native to literature departments (regarding the nature of a text, the function of an author, the relation of form and content, the category of the “literary,” even the basic existence of meaning and intention) that do not really obtain among intellectual historians; these debates, conventions, and priors still guide or dictate research for literary scholars. Intellectual historians, on the other hand, are likely to be fairly oblivious or indifferent to them. Our feel for a text is totally different because the questions we bring to it don’t come from the same disciplinary bugbears and hobbyhorses.

So to be frank, I have far less of an answer as to what intellectual historians might or should do with a novel than some thoughts as to what we are unlikely to do–which isn’t, I realize, a very satisfying answer. But I guess I was thinking somewhat along the lines of the Dewey quote about problems seldom being solved but merely moved on from–intellectual historians might be able to move on more easily when it comes to the novel and its problems. Where we move to? I think you provide a great example of that above (and in your posts as well!).

I promised in the post a list of some novels I’ll likely be reading this summer, as well as a short list of some suggestions of novels that I’d consider novels of ideas and which I’d recommend:

N. K. Jemisin, The Broken Earth Trilogy

Andy,

Just out of curiosity, how would you classify (if you happen to have read it) D. Tartt’s The Secret History? Or are novels set partly or entirely on college campuses sort of their own genre?

As far as novels of ideas by American authors go, I’d throw in a plug for Robert Stone’s A Flag for Sunrise. (Not perfect, but highly enjoyable to read. Not going to take the time to describe it further right now.)

Andy, Yes! I am very interested in the novel and I am thinking about this a lot for my next project. There is so much I think a novel can tell us and since I have little training in how to read them as intellectual artifacts I often find myself going to the literary criticism for help. But, I am not satisfied with that and their must be more to it. So, can we have a panel at the next conference on reading novels as intellectual historians? I need those tools and I think it could open up some amazing path. Thanks.

I think a panel on the novel and intellectual history would be great!

Funny: about two weeks ago, I proposed a panel much as you describe here over on the CFP page for next year’s conference . I only got 1 response — from a cultural geographer rather than a historian! Would definitely be up for something along these lines as the conference in 2019.

Louis,

I really like Tartt’s Secret History a lot, and I think that it could be a good case study of differences between how a literary scholar and an intellectual historian might approach a novel. I’m speaking quite generally and am perhaps caricaturing literary treatments, but hopefully not to the point of inaccuracy.

One of the questions that seems to weigh heavily on literary scholars when dealing with popular novels like The Secret History but which would likely have less bearing on an intellectual historian’s reading is the issue of genre and generic conventions: how does Tartt “deploy” the conventions of the mystery genre or of horror as well as the genre of the campus novel? I used scare quotes for “deploy” because following that issue of genre seems to be a natural question of ends: why is Tartt using these genres? Is there a sort of metacommentary going on which we are supposed to understand because of our knowledge of these genres’ conventions?

I’m not sure that genre would be so readily noticeable to an intellectual historian, or it would less as a kind of writerly strategem than as a response to the climate of opinion in which the novel took shape. The neo-Gothic elements of the novel tie together in a particular pattern that is heavily saturated with both class and homoeroticism–one hardly needs to be pushed to draw connections to the mid-1980s during which the novel was first imagined (when Tartt was an undergraduate at Bennington). The intellectual historian may be treating the novel much more crudely than would the literary critic or scholar by triangulating it with Wall Street and AIDS, but perhaps a certain crudity is occasionally useful. Rather than thinking about the novel’s neo-Gothic elements as part of a commentary on genre or on literature itself, the intellectual historian probably would read them as responses to something in the nature of the AIDS crisis and the changing cultural relationship between Wall Street and the rest of the economy. There was something Gothic about both, and The Secret History captured that connection in a deft, imaginative way (at least in my opinion).

I have yet to read Robert Stone, but have been meaning to! Is Flag better than Dog Soldiers?

Andy,

Thanks, interesting. Been quite a while since I read Secret History and I’m not sure I would have drawn those particular connections but I see what you’re saying. I think even a lit-crit approach would have to acknowledge that the book transcends its genres in some ways. And I do agree that the issues of class are very prominent, built right into the different class background of the narrator compared to the rest of the tight group of friends.

Will answer re Stone later today when have more time.

Yes, this is really good, thanks Andy, how literary scholars would go to “metacommentary…which we are supposed to understand because of our knowledge of the genre’s conventions.” That sort of thing is only occasionally useful for historians because it cuts off parts of what might be said about a novel, and specifically about the world of which it’s a part. Genre discussions can be helpful, say, when the novel is very explicit about the genre it’s commenting upon or “as a response to the climate of opinion in which the novel took shape.”

So I’m with you when it comes what we don’t do as intellectual historians, which suggests to me pragmatic approaches are probably best. Start with a problem and pick up whatever from the conceptual toolbox. Having been to Lit and AmStuds conferences and around those types a reasonable amount, I think sometimes people are surprised by how an intellectual historian reads a particular novel. Sometimes this is for good reasons even. It makes me think of that great moment in the movie Sling Blade, where Carl, the hero, works at a shop fixing small engines and a guy comes in with a problem he can’t figure out, to which Carl exclaims “Mmmm…Ain’t got no gas in it.” The proprietor goes on to mention how Carl is really good at small engines because his mind is simple like that, and so on. So I do think our ignorance of certain things can be a real benefit, that we can enliven things by being a bit less cluttered, that we might even fix some things. It’s worth remembering that Carl spends a lot of time working on engines, much in the way some of us spend a lot of time reading and teaching novels. His mind is less cluttered because he knows the fundamentals of troubleshooting. He looks for the obvious thing first.

So maybe genre and form discussions would appear according to how useful we might find those things for the ideas we mean to explore? There could be a light touch there. That kind of thing wouldn’t be all that dissimilar from cultural commentary in the present day about why a movie like “Get Out” hits the buttons it does by subverting horror film conventions, and so on.

Oh yes, I definitely didn’t mean to say that genre conventions are unimportant or even that intellectual historians shouldn’t consider them as an important part of what makes a novel (or a film) work the way it does. But I think literary folks can fetishize questions of genre; rather than a heuristic category that makes certain elements more visible, genre becomes a kind of force acting within the text that both the author and the critic have to grapple with and pin down.

I wanted to to make a broader comment on this issue, which I’ll place in the main thread, but I’d love to jump in here and say that I think Andy’s formulation “a kind of force acting in the text that both the author and critic [and non-professional reader too?] have to grapple with” is a great description of the subject. Certainly it doesn’t put the idea of the “heuristic category” out of commission, but the problem with the category of genre is that it assumes a whole lot of stability to the basic concept that, upon examination, may not be there.

I’ve been teaching a genre-related upper-div class this semester, The American Crime Novel from Hammett to Mosley, and we have bumped up again and again against the way in which everyone seems to know what genre is as authors shake it, bend it, and make it do things that it wasn’t supposed to. Often authors, too, find themselves put on the defensive by genre labels (Walter Mosley has a good but painful story in his Paris Review interview last year) that others insist on imposing, often mercilessly, as if they were threatened by colleagues getting above themselves.

Now in class we tend to laugh at the US Department of Genres (my bit of whimsy about how American fiction is policed) and most students are behind me when I say that genres exist and persist, but they also change and expand (or contract), and sometimes they even appear disappear. As John Frow argues in his book on this topic from 2014 — more rhetoric studies than lit, which helps — different stakeholders have to negotiate the borderlines of genre on a continual basis. In fiction writing, they have to balance out creative invention, market pressures, editorial preference, reader responses etc, so the crime novelist with an original and searching narrative is rolling the dice in the darkness just as much as the reputed ‘literary’ writer who wants to write a story about murder but not be seen as that kind’ of author.

Andy, thanks for this post, and thanks especially for the recommended readings.

I’ve been spending an awful lot of time with mid-70s to late 80s Norman Mailer lately, and I’ve just damn well had it. I mean, nobody is telling me I have to read the guy, but he’s super-useful for representing and articulating a certain sensibility — ridiculously so. Like William James says, you look at exceptional cases because they magnify the everyday. (I’m paraphrasing liberally, obviously.)

In terms of summer reading plans, for novels I have to stick with what I’m writing about, which is mostly stuff I’ve already read, and stuff from the 50s-80s. No time, looming manuscript deadline, etc.

However, I will be reading lots of poetry and essays by Black women — Audre Lorde, Nikki Giovanni, Maya Angelou, bell hooks. Different genre, but a most welcome change from Norman Mailer.

I haven’t read the Rabbit novels in a few years. But I envision our current President as a more mediocre, less perceptive Rabbit Angstrom — some paunchy, florid-faced insurance salesman or wholesale commercial detergent supplier who’s a so-so golfer but sits in the clubhouse after a round watching The Masters and explaining everything that’s wrong with Tiger Woods’s putting style to the cocktail waitress behind the bar, because she’s trapped and has to listen. This Presidency is the absolute apogee of Rabbit Angstrom’s archetypal career, though we should be so lucky as to hear the vulgar, quotidian musings of this monstrosity delivered with the stunning prose style of Updike ventriloquizing for his creature.

That’s the thing about Updike, above all the rest of the authors you’ve mentioned — who wrote better or more beautiful sentences? As prose style goes, I think he’s absolutely unmatched in post WWII American fiction. He makes everything almost literally tangible to the imagination — which is of course why he casts such a long shadow.

Norman Mailer casts a different kind of shadow. He is the model for a certain kind of nostalgic cosplay on the liberal/Left — the brilliant psychically wounded truth-telling bad boy who doesn’t have the imagination to create a character and so has to be one. So tedious.

But, as I said, so useful.

Another good antidote to Norman Mailer is James Baldwin. So I’m reading a lot of his essays right now — I just got the Library of America volume of his collected essays last weekend, and it’s a real pleasure to spend time in Baldwin’s company, even when he’s saying things that are so true they terrify. You can trust Baldwin, you know?

Anyway, thanks for the post. Wish I could say I had some new fiction on my radar for the summer, but at least some of whatever I read will be new to me, so that’s gonna have to do.

On Stone:

Dog Soldiers is probably his best-known novel, but I don’t think I ever did more than read parts of it. Of the three Stone novels I’ve properly read — A Hall of Mirrors, Children of Light, and A Flag for Sunrise — the last is my favorite. It’s not short, but the first 100 pages or so will give a reader enough of an idea of the style and themes to let one decide whether to finish it or not.

Given some of the concerns you voice in the post, Andy (I’m thinking esp. of the reference to the “toxic masculinity” of Bellow, Roth, Mailer, Updike), I’m not entirely sure you’ll like Stone, even though I think stylistically and substantively he’s quite different from those four (to the limited extent I’m in a position to make such a judgment). But you’ll decide that for yourself, obviously.

p.s. Agree with L.D., above, that Updike wrote beautiful sentences (I remember having to read a couple of the early short stories in high school) but I never got into the Rabbit trilogy (or quartet or whatever it is), and I couldn’t even remember now the title of Roger’s Version (even though I’ve read it) and had to google it. I don’t think I have any Bellow, Roth, Mailer or Updike currently on my shelves (though I do have some, albeit not a whole lot of, American fiction). I guess I can admit that partly because I have no professional stake in these matters.

FWIW, I think I’ve read all the Stone books, some more than once. I would rate them this way:

Dog Soldiers

Outerbridge Reach

A Flag for Sunrise

Bear and his Daughter

Prime Green

Well, the world would be dull if everyone agreed on everything! 😉

More seriously, I can see why Outerbridge Reach might have appealed to you, given your interest in ecological consciousness (if i can use that phrase). I just vaguely recall finding some of it tedious. Might well be a minority view. _A Hall of Mirrors_ was a quite remarkable debut novel (won the Faulkner Award for first novel), so that would definitely be on my list. (OTOH, the movie made out of that, and the one made out of Dog Soldiers, were both quite forgettable, as the NYT obit for him noted.)

Also read Stone’s Outerbridge Reach (that I forgot to mention it is probably an indication that it didn’t make as lasting an impression as the three others).

Sorry to jump in so late, but I wanted to raise a few questions about this discussion. There’s much to be said for a pragmatic, light touch, close cousin of the idea that intellectual history is what intellectual historians do: excessive interdisciplinary openness can easily distract from one’s main work and chance, and literary theory is probably as good an example as any from the recent past.

It’s probably true that the time is ripe to populate the empty category in a fresh way; but altering the kinds of novelists we attend to hardly seems a solution to fundamental issues about novels, the study of “ideas,” etc. [Going back a little earlier into Mailer, to Armies of the Night, might be worthwhile for those interested in “history as a novel/the novel as history,” even though he’s his main character in both.]

One might read what’s going on here as less a disencumbering than a surveilling of the boundaries of intellectual history, with its own “bugbears and hobbyhorses,” maybe even pointing ironically back to the good old days of unproblematic “ideas” expressed at various sites in the trusty “context” — the intriguing suggestion that a novelist may “actually contribute to the theorizing and conceptualizing of the historical subject matter itself” notwithstanding.

Can it really be that that the genre of intellectual historians are going to be “fairly oblivious or indifferent” to issues of “the nature of a text, the function of an author, the relation of form and content, the category of the ‘literary,’ even the basic existence of meaning and intention?” When then will it do, and what will it become?

The parenthetical here seems aimed at me, since I mentioned Norman Mailer, so I’ll respond to it. I’ve been back to Armies of the Night. I’ve been back to the Naked and the Dead, in fact — and then through the essays in Advertisements for Myself, through Mailer’s less impressive “New Journalism” works of the early 70s, through his bizarre novel Ancient Evenings and on. (That was actually the first thing of his besides “White Negro” that I read.) I’m using Mailer in the time period I mentioned (including Ancient Evenings!) because that’s the period I’m covering right now. But his work — fiction or nonfiction or something in between — would be perfectly useful to illustrate more broadly held sensibilities of that time.

I don’t see any nostalgia in Andy’s post for the good old days of pure “ideas” foregrounded against obvious context. In fact, I think Andy is making an interesting interpretive move here, with the focus on the turn(s) of criticism so that it could (arguably) be characterized as a body of thought that unintentionally treats novels as somehow merely “context” and essential ideas in/of/about literature as situated elsewhere, while perhaps the most significant conceptions or sensibilities conveyed by literature of all “brows” — ideas about what is good, what is enjoyable, what is entertaining, what is worth our time — might remain unexamined, even as those ideas shape criticism’s field of vision.

Hi LD –

Thanks for the response. Certainly didn’t intend to imply you haven’t been back to a lot of Norman Mailer. I was just wondering whether, in addition to illustrating something of the sensibility of the sixties, the book has gotten or might warrant some attention as an effort to theorize and conceptualize the paired analogies.

Hi Bill,

I’ll lay my cards on the table. I do hope that intellectual historians will find it easier than literary scholars to extricate ourselves from the coils of the linguistic turn. There were and are valuable lessons to be gained from that moment, but the items I enumerated can be hypostatized, as if they are the most important and most essential questions to be asked about any given text.

That is not to say, however, that I want to approach texts with an old-fashioned confidence in the simple solidity of ideas. I’m not saying we can pull ideas out of contexts like buckshot from a carcass. But there is a difference–an important difference, I think–between caution and obsession when it comes to those questions I listed–“the nature of a text, the function of an author, the relation of form and content, the category of the ‘literary,’ even the basic existence of meaning and intention.” I would prefer that intellectual historians be educated enough to be cautious about those issues but less fixated than literary scholars often (still) tend to be.

Hi Andy – Thanks for the clear, candid statement.

Andy, while it’s a fair comment to say that the notion of the novel of ideas may have a more constricted form for your literary studies colleague than for the intellectual historian, I think there’s not just neat footwork in the move from (a) noting the advantages the latter may bring to thinking about the topic to (b) asserting that literature scholars (presumably Americanists are meant here) are somehow trapped in a kind of generational commitment to the problematic or even reactionary values of a certain group of late twentieth-century novelists. You write:

“To put the matter plainly: I think it is going to be very difficult for people who have primarily studied literature as their main subject to extricate themselves from the legacy of that long disciplinary embrace”

The problem I have with this is that it doesn’t describe any English or related department that I have had anything to do with, or indeed know of via colleagues at other institutions. Even thinking back 20 years to when I started grad school, it doesn’t spark much recognition. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it’s an elegant straw man being satisfactorily taken down, but I think it’s at least somewhat of a false portrayal of the real academic landscape. Three points are worth making in this regard:

1) It’s important to keep in mind that modern or contemporary American literature may only be a small part of what an English department actually does, and the range of specialization even on the American side alone militates against a particularly skewed focus on a small number of late twentieth century writers. In fact, even the earlier inter-war generation faced quite a bit of nose-wrinkling in the 1990s, with Hemingway in particular being seen as hopelessly dated in the gender implications of his fiction (this changed over time as new perspectives on these works were opened up, some of them from scholars dissenting from the dissenters, as is quite normal)

2) The range of names is less than convincing. Any quick survey of faculty teaching modern American fiction, let’s say, at most normal-sized and situated schools will generate not (or not only) the authors listed but, to take just a few examples, Mary McCarthy (pictured), Joan Didion, Toni Morrison, Leslie Marmon Silko, James Baldwin, Thomas Pynchon, Flannery O’Connor, Karen Tei Yamashita, Ishmael Reed, Ernest J. Gaines, Sandra Cisneros, and others.

3) Most importantly, the argument conflates, I think, two somewhat separate (one can argue over the lines) fields where discourse on literature takes place: one is the higher-ed milieu for disciplinary literary studies, including American fiction, and the other is the cultural arena of publishing media, reviewing, and literary journalism. If an overt or covert preferential bias towards the “toxic masculinity” of the Roth/Mailer/Updike front is anywhere, it’s more likely to be found there rather than in the academy.

All that said, just to be clear, I am enthusiastically in favor of having a serious exchange between literary scholars/critics and intellectual historians over the potential value of American fiction for understanding the relationship between ideas and both elite and popular culture.

I would second Martin’s impression here for #2 here. I’ve been to the MLA at least 3 times in the past 5 years, and I haven’t seen a single panel on Bellow or Updike that I can recall. I suspect that if you surveyed current graduate students at the better known graduate programs, many more will have read, say, Silko or Marilynne Robinson than Saul Bellow or John Updike. I can’t think of a single one of my peers who teaches American literature who regularly teaches Bellow or Updike (for precisely the reasons you propose Andy–too intellectual, too masculine, etc.). Roth and Delillo have fared better, I believe, but they too are far less widely read and discuss than they were, say, 15 years ago. If you look at the influences on well-known contemporary writers (Zadie Smith, Junot Diaz, etc.), this mid-century group of Great Male Novelists is not their canon. It’s more figures like Toni Morrison or Salman Rushdie who loom large. I think the bugbear you describe still mattered to figures like David Foster Wallace (he wrote a famous essay on these Great Males) but that this influence has become seriously diminished over the past two decades.

Martin and Patrick,

Thank you for responding–I should definitely clarify what I meant.

I do think that explicit interest–which can be measured by MLA panels or graduate reading lists–has waned in the Great Male Novelists. But that wasn’t really what I was arguing. When I talked about “inertia” above, I was thinking less about which authors are studied and more about the ways that new research is framed.

My argument was that the study of authors like those you listed above are typically not justified in the way that the Great Male Novelists were: it is not their braininess but their ability to speak to a certain kind of (often racialized) experience or their ability to meld different genres creatively or both.

Now, a number of the Great Male Novelists were studied both for their braininess and for their Jewish-American-ness, I recognize. But often those research currents were intertwined or even merged. Their braininess was an expression of their Jewish-Americanness, and vice versa.

I’ll be frank and say that I haven’t kept very current with cutting-edge scholarship in 20th c U.S. literature, but it seemed to me when I was that, even such obviously intellectual authors as Zadie Smith or Junot Diaz or Toni Morrison or Ishmael Reed, the points of attraction for critics and the points of justification for scholars rested on different premises.

Now, two points further are important to add here.

First, I do think it is valid to conjoin–I don’t think I’m conflating–critics and scholars in this argument. Scholars–at least of 20c literature–don’t write much about unpublished authors, and critics’ preconceptions of what kind of literature is “brainy” or intellectual has a pretty big role in determining what gets published and marketed as such, and what gets published and marketed as an “Asian-American novel” or as a novel about women’s experiences. Sure, Garth Risk Hallberg or Chad Harbach might not become staples of undergrad reading lists or MLA panels, but they were certainly poised as the heirs of the Brilliant Mid-century Male Novelists in a way that, say, Meg Wolitzer or Rachel Kushner are not. To imagine that this process of critical prejudgment has no bearing on the way that scholars approach the novelists that they do write about seems a little strange.

The second point is that there is obviously a lot of scholarship that thinks through Morrison or Baldwin or Silko (et al.) as theorists of race and/or gender. But this is where I think the inertia of the discipline comes to the fore: I don’t think that theories about race and theories about, say, technological change are treated the same in English. Pynchon is still treated somehow as more intellectual than Morrison.

That probably is not a point of distinction with intellectual history. Intellectual history as a field still too often treats the subjects that, say, Daniel Bell wrote about as if they were somehow more intellectual than the things that Shulamith Firestone wrote about. That’s a problem the disciplines share.

I think intellectual historians have an advantage, however, if they can move onto terrain that they have not spent as much time in and can come to with fresh eyes and–hopefully–fewer preconceptions about who is and who is not “intellectual” or “brainy.” That was my point above.

Hi all —

This was a great post, Andy! I’ll make one comment and pose one challenge. Here’s the challenge: what examples do we have from important works of IH scholarship that successfully comment on works of fiction? That is to say, can you think of a major work of IH scholarship that a) uses the methods of IH to illuminate a novel in a particularly important way, or b) incorporates a novel (non-reductively) into its historical story? I ask this question b/c I can’t think of a single example off the top of my head. If I recite some big names in IH (Kloppenberg, Jay, Radner-Rosenhagen, D. Rodgers, H. Brick, Hollinger, Bender, Igo, etc.) I can’t recall a single work of fiction being important to their arguments. Maybe I’m overlooking something obvious here, but it is striking to me that we are 25 comments deep into this post and not one person has mentioned an example of successful IH treatment of fiction. George Cotkin’s recent _Feast of Excess_ may be one candidate, but I haven’t read it yet. Can you think of others by current practitioners? I can think of lots IH work written by literary critics (Kazin, Greif, Posnock, Dickstein, Poirire, Bromwich, Menand, ec.), but none of these names would count as “properly historical” in the eyes of the IH community. These are literary critics crossing the border. What about the opposite scenario? (Again, Cotkin’s name comes to mind: he’s written a book on Melville, I believe).

(I wish I had more space to discuss genre. I largely agree with Andy that literary critics make too much of it, at the expense of the many other contexts available. I was just teaching Morrison’s _Sula_ this week, which was written in 1969-1972. Yet very little of the scholarship addresses its historical setting).

One of my favorite articles about the issues raised here is Sara Maza’s “Stephen Greenblatt, New Historicism, and the New Cultural History, or What We Talk About When We Talk About Interdisciplinarity” MIH (2004): 249-265. She raises many of the same concerns raised by Andy, namely, the historian’s reluctance to multiply meanings vs. the literary critics penchant for doing so. The reason for these biases, she points out, has to do with their diff. relations to the object of study. Historians _construct_ their object, while literary scholars typically approach an object that has already been _constructed_ (published, printed, etc.). Maza frames it this way:

“As Gabrielle Spiegel points out, the fundamental difference between literary and historical scholarship as done today is that literary scholars are trained to work with an existing object (say, the novels of Jane Austen), whereas historians are taught to construct an object of study (for instance, social structure in nineteenth-centuryHamburg).As Spiegel points out:

“The task facing the [historian] is broadly constructive, that facing [the literary

critic] broadly deconstructive.” Hence, while nearly all historians believe in

the ultimate reality of the past, they approach that reality much more gingerly

than do their literary colleagues. Fully aware of the many choices and extensive

labor that go into the task of historical reconstruction, they are both less likely

to invoke the past’s “reality” but also wary of acknowledging double and triple

meanings or the self-subversion of a source: a document can only mean one

thing if it is to serve as one element of a large pattern. Literary critics, by contrast,

write as if there was an agreed-upon historical “reality” which can enhance or

enchant works of art (“the touch of the real”), but also must serve as a target for

deconstruction.

That distinction always seemed very clarifying for me — it is largely true of my own practices as a historian–i.e. I tend to work with published documents. That is typically not the case for most of the people who read this blog, I think–there’s a certain prestige in having “gone into the archive” for unpublished material. Indeed, I think it’s fairly safe to say that you aren’t considered a “real” historian unless you take this step. I wonder what others think about this impression.

Re the challenge in the first paragraph: not entirely sure, but Greg Grandin’s The Empire of Necessity: Slavery, Freedom, and Deception in the New World (2014; pb, 2015) might count w/r/t reconstructing the historical event(s) treated fictionally by Melville in Benito Cereno.

I can think of one or two older books on European intellectual history that treat novels “non-reductively” — e.g., H. Stuart Hughes, The Obstructed Path — but your ‘challenge’ seems to be limited to U.S. intellectual history.

Hi Patrick,

That’s a great quote, and thank you for pointing me to the article!

I *don’t* think there are intellectual historians who have engaged consistently over their career with fiction in the way that I’m asking for in the post above. And that is why I think there’s an opportunity here: without a bulky tradition to negotiate, intellectual historians can be a little less self-conscious, a little more supple in their readings. They can bring, as I said, fresh eyes–or in the words of Bunk from The Wire, “soft eyes”–to fiction. And just as importantly, that freshness can extend not only to how they look at fiction, but also to what kind of fiction gets graded as appropriate or useful. Even if we hold up a standard of textual “complexity” or “seriousness” of thought, there’s not a predetermined set of novels that qualify–intellectual historians can kind of construct those categories as we go along.

Great post, Andy, and I’ve enjoyed catching up on this conversation. One book that might meet the challenge criteria above, and has influenced how I use literary sources to write intellectual history:

Eric J. Sundquist, To Wake the Nations: Race in the Making of American Literature (1998).