Editor's Note

For nearly two decades, I’ve taught an undergraduate Honors Course at the University of Oklahoma built around the readings in Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition. As part of LD Burnett’s series of posts rereading Hollinger & Capper, I’m doing a series of posts exploring what it’s like to teach the volumes in an undergraduate, honors setting. Last week, in my first post, I said a few general things about Perspectives on the American Experience: American Social Thought, the course (or actually courses) in which I use The American Intellectual Tradition. When I began this course, The American Intellectual Tradition was in its 3rd edition. Unless otherwise noted, I’ll be blogging about the most recent edition of the books, the 7th. In this second post in my series, I discuss teaching Volume I, Part One, entitled “The Puritan Vision Altered.” For more on Volume I, Part One, see LD’s post about it. Next week, I’ll blog about teaching Volume I, Part Two (“Republican Enlightenment”). After that, having caught up with LD, I’ll be blogging about a new section every two weeks as LD works her way through the book.

“Let us thank God for having given us such ancestors; and let each successive generation thank him, not less fervently, for being one step further from them in the march of ages.”

– Nathaniel Hawthorne, “Main Street” (1849)

For the undergraduates in my American Social Thought course, beginning Volume I of The American Intellectual Tradition can feel like being tossed into the deep end of the pool. In many ways, the Puritans represent the most challenging readings of the semester. They are furthest removed from my 21st-century students in language and thought. And, due to the continuing mythic presence of the Puritans in American culture, some of what students think they know about them can interfere with their understanding these texts.

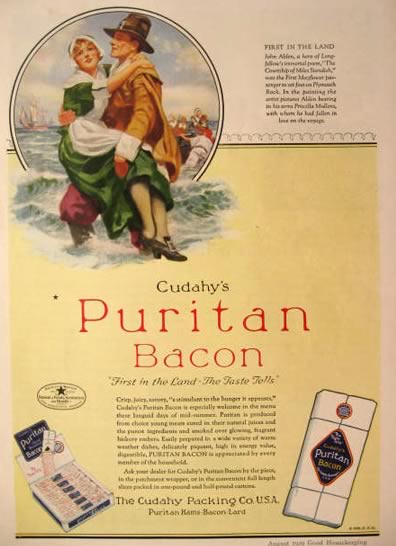

This 1929 ad for Puritan Bacon confusingly features an image of the Pilgrim John Alden carrying Priscilla Mullens from the Mayflower to Plymouth Rock.

For all the years that I’ve used Hollinger & Capper in my lower-division Honors Course, I’ve always taught the Puritans with many warning labels attached. Their language is difficult to read, so don’t get discouraged (and things will get easier…even before we finish this section of the book). Always remember that not everyone in British North America were Puritans; indeed, outside of New England, practically nobody was. Despite their bitter relationship to church authorities back in England, the Massachusetts Bay Puritans were not

separatists. While the Puritan reputation for intolerance was well-earned, Puritans frequently disagreed with other about religious matters; to conclude that Puritans accepted no disagreement whatsoever is to misunderstand them. One of the tricks in reading the early Puritan materials in The American Intellectual Tradition involves understanding why certain kinds of dissension were tolerated and others were not. And, of course, in order to understand any of what is going on in the Puritan readings, you need to have some understanding of seventeenth-century Calvinism, especially the doctrines of unconditional election and predestination.

For years this meant that I spent an awful lot of time providing context for the early readings in The American Intellectual Tradition to my students. This was an awkward way to start the semester. To begin with, it’s not my period and I am anything but a specialist in Puritan thought. And as the course went from its initial lecture-plus-discussion format to an all-discussion format, my starting the semester talking an unusual amount made it more difficult to encourage student discussions as we got into the semester.

As I noted in my last post, my decision several years ago to spend an entire semester on a single volume of Hollinger & Capper freed up a few weeks for additional readings. And the first book I decided to add to the syllabus was Michael Winship’s The Times and Trials of Anne Hutchinson (University of Kansas, 2005). This short book provides both an excellent general account of Puritanism and also specific context for three of the key readings Part One of The American Intellectual Tradition: John Cotton’s A Treatise of the Covenant of Grace (1636), “The Examination of Mrs. Anne Hutchinson at the Court at Newtown” (1637), and Roger Williams’s The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644).

These days, I begin the course with the very first reading in Part One, John Winthrop’s lay sermon “A Modell of Christian Charity” (1630), which we discuss as a class in our second (of two) meetings during the first week of the semester. Though Winthrop’s language is difficult, “Modell” is conceptually easier than the other seventeenth-century Puritan texts in the book. To some of the students, it is also familiar. Or, rather, its image of a “City upon a Hille” (borrowed from Matthew 5:14) is. Tackling Winthrop first (and overcoming his difficult language) builds confidence in my students. Winthrop’s discussion of class and the proper order of society and his understanding of the relationship of the Puritan expedition in Massachusetts to the broader world set up issues that will resonate throughout the semester. And starting with Winthrop’s sermon also lets us consider questions of canonicity: this sermon was not a very significant text until it was reprinted a couple centuries later. Since then it has become something of a touchstone in U.S. political culture.[1]

But we then spend the second week of the semester reading Winship’s book, which makes them more prepared to tackle the other 17th-century readings (Cotton, Hutchinson, and Williams), which we read for the third week of classes.

I still end up having students who, e.g., misidentify Winthrop as a minister, suggest that Massachusetts Bay was a theocracy, argue (usually without evidence) that the only reason Anne Hutchinson was exiled is that she was a woman (oddly often while also claiming that the Puritans punished all dissent), or write about the seventeenth century as if everyone alive during it was a Puritan. But reading Winship greatly improves the start of the semester by helping my students get their feet wet before proceeding into the deeper waters of Cotton, Williams, and the Hutchinson trial.

* * *

The second half of Part One of Volume I of The American Intellectual Tradition leaps forward to the eighteenth century. When I taught excerpts from both volumes in a single semester, the only readings I’d do from the latter half of this section were the two Jonathan Edwards pieces, the sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” (1741) and the selections from A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections (1746).

But I’ve enjoyed adding the other two readings: selections from Cotton Mather’s Bonifacius (1710)[2] and, especially, Charles Chauncy’s Enthusiasm Described and Caution’d Against (1742). In her post on Part One, LD suggested that the first reading that she’d ditch from it – were she proposing ditching any readings, which she was not – would be the Chauncy. So let me put in a plug for Enthusiasm Described and Caution’d Against, which I’ve come to think is pretty indispensable in teaching this material.

Given half a chance, my students want to imagine consensus lurking behind just about every document we read. This is why, despite my repeated warnings, everyone in seventeenth-century British North America becomes a Puritan and Puritans brooked no disagreement about anything. So it’s vital to add to our readings of Jonathan Edwards, that leading New Light, a sermon by an Old Light minister like Chauncy. Chauncy’s sermon accomplishes more than simply instantiating the fact that what was later known as the Great Awakening was not a period of religious consensus. Chauncy is also a fascinating mixture of the new and the old. As the book’s introduction to this reading notes, Chauncy was in many ways a theological liberal. He’d eventually embrace Arminianism, that is, the idea that humans can participate in their own salvation.[3] And students quickly pick up on the similarity between his method of distinguishing whether one’s experience is the Spirit’s actually leading one to God or mere enthusiasm and John Cotton’s method of distinguishing between revelation and delusion in the trial of Anne Hutchinson. Both Cotton and Chauncy see agreement with Scripture as crucial; God can communicate directly with you, but if what He appears to be saying is not simply reinforcing Scripture, it is not God that you are hearing. (When students encounter John Humphrey Noyes later in the semester, they’ll see a total rejection of this metric.)

I do all the 18th-century readings that round out Part One of Volume I of Hollinger & Capper during the third week of the semester. Students then have to write an essay on the material that we’ve covered up to that point in the semester. This year, I asked them to choose one of the 17th-century texts and one of the 18th-century texts and compare them. What do the two thinkers have in common? What is different? And how do you explain the differences you see?

Although the language of the 18th-century works in Part One is dramatically easier to follow than that of the 17th-century ones, most of my students are delighted when we close the book on the Puritans and their immediate heirs and turn to Part Two of The American Intellectual Tradition, Republican Enlightenment. My next post next week will concern the four weeks of the class that I spend on those texts.

Notes

[1] My Doktorvater Dan Rodgers is currently at work on a book about the history of Winthrop’s sermon in American thought and culture.

[2] Incidentally, one of my pet peeves when teaching from these volumes is students’ tendency to refer to, e.g., “Cotton Mather’s Selection from Bonifacius.”

[3] Edwards, for his part, held firm to the orthodox Calvinist position that they cannot, that salvation is predestined and election unconditional…which raises one of the questions I always ask my students to grapple with: if people cannot achieve salvation through their free will, what does Edwards think he’s achieving with the hellfire and brimstone of “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”?

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Ben, I have occasionally taught the Puritans — also as a non-specialist — on the American literary history side, and generally encountered a similar combination of assumed knowledge and actual difficulty to grasp the multifaceted nature of the subject. One text/author who can upset the students’ historical framing early on is Thomas Morton, and selections from A New English Canaan can be relatively easily found that buttress the notion of the Puritans (and the Pilgrims who need some distinguishing from them) as a minority trying to become a majority in the New World. And Morton challenges the very language of the Puritans in his account, a much wittier and more stylistically urbane work than, say, Bradford, Winthrop, or even Williams. In a literature class, however, It is a bit easier to assign Hawthorne’s short stories “The Maypole of Merrymount” and “Endicott and the Red Cross” later to show how New England history tended to just forget Morton as a weird blip on the 17th century screen. And of course The Scarlet Letter is great for bringing back students’ minds to Ann Hutchinson and reminding them that the Puritan legacy was one that nineteenth-century New Englanders struggled with.

Thank you, Ben, very useful. Looking forward to future posts.