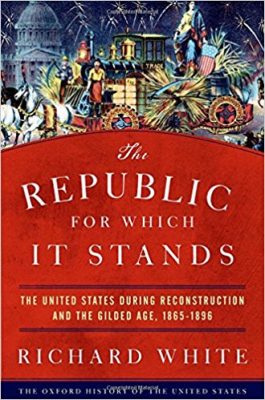

I have been reading The Republic for Which It Stands, Richard White’s new synthesis of the three decades after the Civil War, and it is—as anyone could have predicted—magnificent. This period has always defied a kind of holistic, multi-regional narrative, one that adequately encompasses Reconstruction in the South, imperial conquest in the West, and industrialization in the Northeast and Midwest. The sheer scale and scope of the period, the arrogant vastness of its canvas, has paradoxically forced historians to use figures of consolidation and stabilization to try to get a hold of its elusive unity. It is an age of “incorporation” (Alan Trachtenberg), or of a “search for order” (Robert Wiebe), one well-described by an “organizational synthesis” (Samuel Hays and Louis Galambos) increasingly guided by a “visible hand” (Alfred Chandler). Yet everyone knows that the lived experience of these decades defies these confident titles. White’s synthesis is perhaps the first to adequately portray the era’s anarchy while still providing a clear and detailed map to its chaos.

I have been reading The Republic for Which It Stands, Richard White’s new synthesis of the three decades after the Civil War, and it is—as anyone could have predicted—magnificent. This period has always defied a kind of holistic, multi-regional narrative, one that adequately encompasses Reconstruction in the South, imperial conquest in the West, and industrialization in the Northeast and Midwest. The sheer scale and scope of the period, the arrogant vastness of its canvas, has paradoxically forced historians to use figures of consolidation and stabilization to try to get a hold of its elusive unity. It is an age of “incorporation” (Alan Trachtenberg), or of a “search for order” (Robert Wiebe), one well-described by an “organizational synthesis” (Samuel Hays and Louis Galambos) increasingly guided by a “visible hand” (Alfred Chandler). Yet everyone knows that the lived experience of these decades defies these confident titles. White’s synthesis is perhaps the first to adequately portray the era’s anarchy while still providing a clear and detailed map to its chaos.

The book’s insights are abundant, but I’m not trying to review it. Instead, what caught my eye was a quotation error. It’s not even a very big error, but its stakes end up being rather large: what did “free labor” mean to Abraham Lincoln?

***

One of White’s main themes is the importance of the symbol of home within the ideology of the Republican Party and within the political culture of Reconstruction and the Gilded Age more generally. “Home was a concept so pervasive that it is easy to dismiss it as a cliché and to miss its particular resonance in this historical moment,” he writes.

Home, in the fullest meaning, links to other concepts—manhood and womanhood—which took shape around it, and to another concept that was disappearing from common use by the end of the century: a competency or competence. Home with these satellite notions provided the frame in which ordinary nineteenth-century Americans understood their own lives, the economy, and the national goals of Reconstruction in the South and West… (White 2017, 136-137)

White is here drawing on the work of Amy Dru Stanley, whose From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Market in the Era of Slave Emancipation explored the mutation of free labor theory from an at times radical antebellum rejection of bonded labor to an at times mendacious defense of what others called “wage slavery” after the War. Backing away from the fuller implications of their critique of unfree labor, Liberal Republicans and Unionist Democrats instead sought refuge in a highly formalistic defense of contract theory, accepting without reservation the “inevitability” of a permanent class of wage laborers.

For Stanley and for White (and for a number of other historians), this ideological shift at least feels like a betrayal: the retrenchment of the Liberal Republicans on issues of labor—like their abandonment of the projects of African-American enfranchisement and land redistribution—was a devastating political pivot and a craven intellectual surrender. Rather than press forward with any of the emancipatory causes that seemed so tangibly possible during the War—from women’s rights to meaningful distribution of productive property to freed slaves and poor whites—the liberals in both parties found clever ways to stymie and even to reverse forward progress.

Often underneath this line of criticism is a tacit accusation of hypocrisy—or if not hypocrisy, of negligent obliviousness. Postbellum Republicans were so impressed with the symbol of the home that they ignored how rapidly the wage labor system was closing off the opportunities to obtain one—to attain that “competence” which White salutes in the passage I quoted. So proud were they of the grand strokes of the Homestead Act or the completion of the transcontinentals that they failed to ask whether those bold initiatives actually made anyone’s life better. (Well, anyone who didn’t have stock in Union Pacific.) Some of them didn’t ask because they didn’t want to know the answer; some didn’t ask because they already knew what the answer was.

One of the hard cases in all this is Abraham Lincoln himself. In The Republic for Which It Stands, White portrays Lincoln as trapped from within a gauze of his own myth, convinced that his life’s journey from railsplitter to President was proof positive of the continuing functionality of the “free labor system.” Oblivious to the realities of proletarianization and the shrinking of opportunities for workingmen to attain that essential “competency,” Lincoln affirmed the beauty of the status quo.

One of the hard cases in all this is Abraham Lincoln himself. In The Republic for Which It Stands, White portrays Lincoln as trapped from within a gauze of his own myth, convinced that his life’s journey from railsplitter to President was proof positive of the continuing functionality of the “free labor system.” Oblivious to the realities of proletarianization and the shrinking of opportunities for workingmen to attain that essential “competency,” Lincoln affirmed the beauty of the status quo.

And here’s where I found something I’d like to quibble with White—and behind White, some other historians who have done something similar. Here is how White quotes Lincoln:

Abraham Lincoln had both embraced and symbolized the opportunity, achievement, and progress that a competence represented. In 1860 he had told an audience in New Haven, Connecticut, “I am not ashamed to confess that twenty-five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son.” But in the free states a man knew that “he can better his condition … there is no such thing as a freeman being fatally fixed for life, in the condition of a hired laborer…?.?The man who labored for another last year, this year labors for himself, and next year he will hire others to labor for him.” If a man “continues through life in the condition of the hired laborer, it is not the fault of the system, but because of either a dependent nature which

prefers it, or improvidence, folly, or singular misfortune.” The “free labor system opens the way for all—gives hope to all, and energy, and progress, and improvement of condition to all.” After his death, Lincoln’s personal trajectory from log cabin to White House served as the apotheosis of free labor. Anything was possible for those who strived. (White 2017, 138)

The trouble is, this is a kind of mash-up of quotes from two different speeches: Lincoln’s Address Before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society on September 30, 1859, and from his speech a little over five months later (March 6, 1860) in New Haven, Connecticut. White’s footnote is actually not to the Collected Works, but to James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom.

To be clear, I’m not trying to ding White for not using the primary source version, and his confusion is easy to understand: McPherson’s discussion of Lincoln’s ideas is tangled, and he only acknowledges that he’s drawing from more than one speech in the footnote—“CWL, II, 364, III, 478, 479, IV, 24.”[1] And actually—as you can see—he’s pulling material from three: the Volume II citation is from Lincoln’s August 27, 1856 speech at Kalamazoo, Michigan; the cite from Volume III refers to the Wisconsin Address; and the one pulled from Volume IV is the New Haven speech. In the body of the text, it is only the New Haven speech that McPherson mentions.

Now, all three speeches share some important elements, and the reason that McPherson grouped them together is that they all have some variant of Lincoln’s declaration that “The man who labored for another last year, this year labors for himself, and next year he will hire others to labor for him” (“Kalamazoo”). All three speeches also have some denial that there is a “class” “fatally fixed for life” to being hired labor.[2] In other words, there is a totally valid reason for linking these speeches together. McPherson probably should have noted in the body of the text that he was doing so, but any resulting confusion is almost certainly innocent and inadvertent.

Confusion over this rather free paraphrasing of Lincoln’s position on free labor is not, however, insignificant. One of the reasons that McPherson felt comfortable stitching together a single statement out of these three speeches is that—at least since Eric Foner’s classic Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men—Lincoln has been taken as a symbol of the free labor position’s “inherent ambiguities”—which I think was Foner’s way of saying “unacknowledged contradictions.” Here’s what Foner had to say about Lincoln in the 1995 reissue of Free Soil:

Confusion over this rather free paraphrasing of Lincoln’s position on free labor is not, however, insignificant. One of the reasons that McPherson felt comfortable stitching together a single statement out of these three speeches is that—at least since Eric Foner’s classic Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men—Lincoln has been taken as a symbol of the free labor position’s “inherent ambiguities”—which I think was Foner’s way of saying “unacknowledged contradictions.” Here’s what Foner had to say about Lincoln in the 1995 reissue of Free Soil:

Even though, by the 1850s, he lived in a society firmly in the grasp of the market revolution (and he himself served as attorney for the Illinois Central Railroad, one of the nation’s largest corporations), Lincoln’s America was the world of the small producer… Yet even Lincoln’s eloquent exposition could not escape free labor’s inherent ambiguities. Was wage labor a normal acceptable part of the Northern social order or a temporary aberration, still associated with lack of genuine freedom? To some extent, the answer depended on which laborers one was talking about. (Foner 1995; 1970, xxvi).

There is a palpable undercurrent of criticism: Lincoln (Foner implies) blinked in the face of change, seeking to explain it away, even to explain away the ways he was acting hand-in-glove with those changes. He was maybe a little provincial (Illinois is a long way from New York or Lowell), but he also cherished the protections of his provincialism.[3]

Historians love irony, and there is great irony and even a bit of pathos in the idea of Lincoln and Lincoln’s party striving to remake the world in the image of a small city already under siege by the engines of modernity. It is a little like Walt Disney setting up “Main Street U.S.A.” just as the culture industry revved up its assaults on the sweet and sleepy distinctiveness of the American small town. Or like Henry Ford constructing Greenfield Village: the vanguards of change are often those whose hearts seem most at home in the community they have obliterated.

That, at any rate, has been a sort of morality tale that numerous historians have gotten used to telling about the ideology of free labor, the Republican Party, and Abraham Lincoln. But I think the historian’s penchant for tragic irony has overwhelmed some of the more fine-grained nuances in Lincoln’s ideas about free labor—nuances that especially drop out when we smush his speeches together as in the passages above. In a subsequent post, I want to take a closer look at what Lincoln actually said in each speech. While not enormously different, I think that the interpretation of free labor ideology which emerges is importantly different.

Notes

[1] Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Ballantine, 1989), 28.

[2] “They [Southerners] think that men are always to remain laborers here—but there is no such class” (“Kalamazoo”); “there is no such thing as a freeman being fatally fixed for life, in the condition of a hired laborer” (“Wisconsin”); “When one starts poor, as most do in the race of life, free society is such that he knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life” (“New Haven”).

[3] Foner, for his part, footnotes this paragraph by citing the Wisconsin Address once again, but also by noting a kindred passage in his June 26, 1857 Speech at Springfield, Illinois and a “Fragment on Free Labor” that the editors of Lincoln’s Collected Works have dated to 1859. And White, similarly, alludes to Lincoln’s provincialism by stating that “In its simplest form the Greater Reconstruction boiled down to Springfield, Illinois. This was as close as any actual place could be to the template that the North planned to use in recasting the South, as well as the West. Springfield and its surrounding farms were the world of Lincoln.”

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andy, thanks for this wonderful post. A couple of things…

First, White’s book is heaven-sent for me, as an opportunity to return to a time period I love but am not currently working in, and also as an affirmation of sorts. Before I shifted my research to the canon wars, I was working on “the idea of home” from the early 19th century to the late 20th century. But I had a professor tell me that that was a boring topic for research. I didn’t think so then, and I still don’t think so now. So White’s book was a benediction of sorts on my instincts for what matters.

Second, I really like what you’re proposing to do in disentangling the synthesis of the Lincoln speeches and considering them one at a time. One of the perpetual challenges we intellectual historians face, I think, is treating texts as roughly synchronous versus treating them as discrete diachronic utterances. I see this show up in Andrew’s War for the Soul of America, but also in Daniel Rodgers’s Age of Fracture. When we’re talking about conceptual or epistemic shifts we can tend sometimes to group texts together as articulating a particular theme, no matter the order in which they were written. And that’s a perfectly viable approach, to subordinate mere chronology to a more significant organizing principle — usually a particular concept or sensibility that we wish to foreground, and that we may find in a multitude of texts published at roughly the same time, give a take a couple of years.

That’s not a wrong way to write history — indeed, it seems to have been wonderfully effective — for Andrew, for Daniel Rodgers, and most recently for Prof. White.

However, as your post reminds us, every historiographic choice comes with benefits and costs. I look forward to your next post discussing the granular nuances we lose when we regard Lincoln’s thinking on free labor as “of a piece.”

Like L.D., I’m looking forward to the next post.

I did a little research on this general topic (though not on Lincoln’s position and speeches specifically) for a post that I wrote on my (no longer active) blog in 2011. I had occasion to cite McPherson and also Foner’s 2010 book The Fiery Trial. The post was not, as I say, specifically concerned with Lincoln’s position, except insofar as I cited Foner’s view that Lincoln viewed wage labor as a stepping stone to independent artisan-ship or entrepreneurship, precisely at the time when wage labor was becoming a permanent and significant feature of the U.S. economy. From reading Andy’s post here, I take it that that summary of Lincoln’s view is what Andy is going to qualify or complicate in the next installment.

p.s. I also mentioned, in a note to that post, two books by Jonathan Glickstein, not that I’d read them but I ran across the titles in the course of my brief research: American Exceptionalism, American Anxiety: Wages, Competition, and Degraded Labor in the Antebellum United States (2002) and Concepts of Free Labor in Antebellum America (1991).

Thanks for these great comments! I hadn’t initially planned to write two posts about this issue, but I’m relieved to know that you’re interested in hanging around for part 2!

L.D.,

I’m remembering that you’ve posted on here before about that former project on homes–didn’t you do a post or two on the song “Home, Sweet Home”? I thought that was great stuff, and I hope reading White’s new book will give you not just a benediction for your instincts, but also a dialogue partner for returning to some of that territory!

What is becoming clear to me about some of the recent scholarship on homes–I’m thinking of Susan Matt’s book on homesickness but also Elaine Lewinnek’s book on Chicago and some of the research on race and homeownership/the mortgage market, like Beryl Satter’s Family Properties–is that “the home” is a naturally intersectional category that makes the interlocking vectors of race, class, and gender particularly clear. It also is almost effortlessly a way into political economy–or, if you like, to the history of capitalism. So it has many advantages as a focal point for a historical study!

And thank you for your comments about the difficulties of balancing diachrony and synchrony–that’s a really nice way to put it. That gives me some added material to think about as I’m writing part 2!

Louis,

Well, I’d love to read the post if it’s still accessible! I do want to complicate the view–and I think it is, as you suggest, largely Foner who really crystallized it–that Lincoln was so convinced that wage labor was (for all but a few slackers) a temporary stage on the way to property-ownership and a competence. Or, at least, I don’t think Lincoln was so naive as to believe that one could climb out of wage labor by thrift and hard work alone. But I’ll save that for Part 2 🙂

Andy,

Here’s the link to my 2011 post. It’s quite short and I certainly don’t make any great claims for it, but fwiw:

http://howlatpluto.blogspot.com/2011/05/dignity-of-labor.html