This being the first Sunday of Black History Month—a favorite time of year for me—I wanted to do a brief rundown of some recent book releases pertaining to African American history. It’s already been an exciting year for black history as a field, and the rest of 2018 is going to be wonderful if you’re a historian of the African American experience. Two key themes arise regarding what kinds of book are coming out this year.

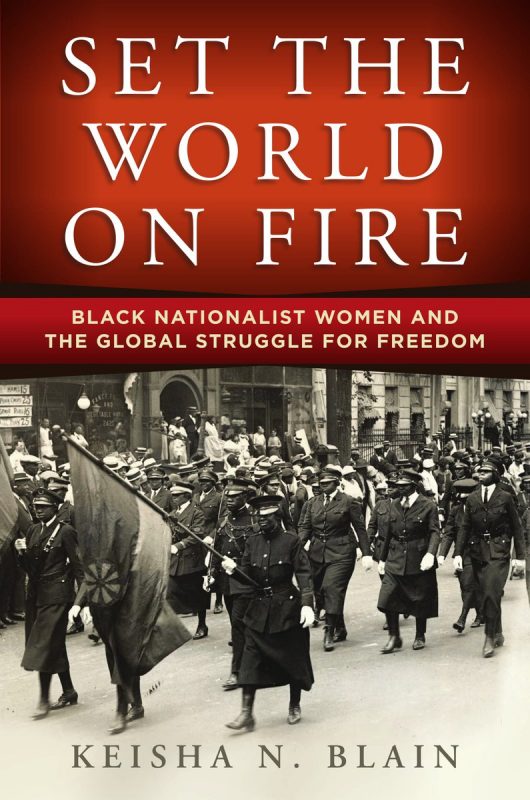

Books such as Ashley Farmer’s Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era and Keisha Blain’s Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom do two things: they re-center the history of black radicalism on black women and remind us of the inherently internationalist outlook such movements always possessed. Other monographs, such as Jeanne Theoharis’ The Rebellious Life of Rosa Parks, Danielle McGuire’s At the Dark End of the Street, or Barbara Ransby’s Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement are earlier practitioners of centering  the black radical experience around African American women. But Farmer and Blain’s books both update the timeline of this experience, moving away from the Black Power and looking back to the 1920s and 1930s as critical moments when black women were heavily involved in black nationalist and Communist movements.

the black radical experience around African American women. But Farmer and Blain’s books both update the timeline of this experience, moving away from the Black Power and looking back to the 1920s and 1930s as critical moments when black women were heavily involved in black nationalist and Communist movements.

It is no surprise that these books are being written at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement—a campaign that has been shaped, and led by, black women. The relationship between writing history and events taking place as that history is being written is not a new observation. But we should remain cognizant of this. It is especially important to keep in mind when considering how radical activists of today are continuing to look to the past for both inspiration and for tactics to use in the here and now. That Blain (senior blog editor) and Farmer (2018 conference co-chair) are also critical to the success of Black Perspectives, the African American Intellectual History Society’s blog, is not surprising either. Black Perspectives as a blog has fulfilled the same role earlier journals and newsletters did—uniting academics with lay citizens in both a collective love of African American history, and a shared belief in responsibility for making the United States a better nation for all its citizens.

In that same vein, historians are also casting a closer eye at the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement. Jeanne Theoharis’ A Beautiful and More Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History approaches the topic of civil rights memory with the care it requires. This and Jason Sokol’s The Heavens Might Crack—on the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.—are both timely books due to their coming out in the fiftieth anniversary year of MLK’s assassination. It will be interesting to see what Sokol does with this topic, as he’s already written a great deal on the average white Southerner and Civil Rights (There Goes My Everything) and Northern hypocrisy on civil rights liberalism (All Eyes Are Upon Us). Theoharis, as mentioned above, has approached how Americans think about the civil rights past through the prism of understanding Rosa Parks. They both also add to work done by historians such as David Chappell (Waking From the Dream), among others. Public memory of the past can be an effective tool for politicians to, for example, either dissuade or promote social protest movements. Memories of the past also tend to collide with history, as we can often see with the debate over the Confederate memorials that dot the American landscape.

Intellectual historians of the United States will have to wrestle with these two themes for years to come. The intersection of gender, race, and American radicalism should bear still more fruit in terms of monographs and journal articles in the coming decade. Linking, for example, black women operating in the late nineteenth century within activist movements with their ideological descendants in the early twentieth century could be a fascinating way of thinking about twentieth century radicalism. As we get further away from the nineteen eighties and nineties, I also think linking women from the Black Power era to women operating in, for instance, the Rainbow Coalition or the Black Radical Congress will not only be inevitable, but a necessity for making sense of the current state of African American radicalism.

Memory of the past will continue to also interest American intellectual historians. The wide disparity in the ways in which Presidents Obama and Trump, for instance, constructed a shared American past through their speeches and political gestures should make us all think harder about how a collective memory of the past has often eluded the grasp of politicians, intellectuals, and scholars alike. That memory of the Civil Rights Movement is often used to suppress modern calls for equality and justice in America gives the scholarly interest in memory a new and sometimes stunning urgency. The historians mentioned in this essay, along with many others, are taking up the call for such scholarship with gusto.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Robert,

Thanks for the informative and timely post. I just wanted to note, lest readers draw the wrong inference, that Barbara Ransby’s book also deals with the 1920s and 1930s, as well as the ’40s and ’50s until the second half of the book, which covers Baker and the Black Freedom Movement as incarnate in the 1960s and the early 1970s (so too, of course, does Carol Boyce Davies’ book on Claudia Jones treat the earlier half of the twentieth century).

Thanks for the clarification–and the mention of Davies’ book on Claudia Jones.