Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts on the common readings in Stanford’s 1980s “Western Culture” course. You can see all posts in the series here: Readings in Western Culture.

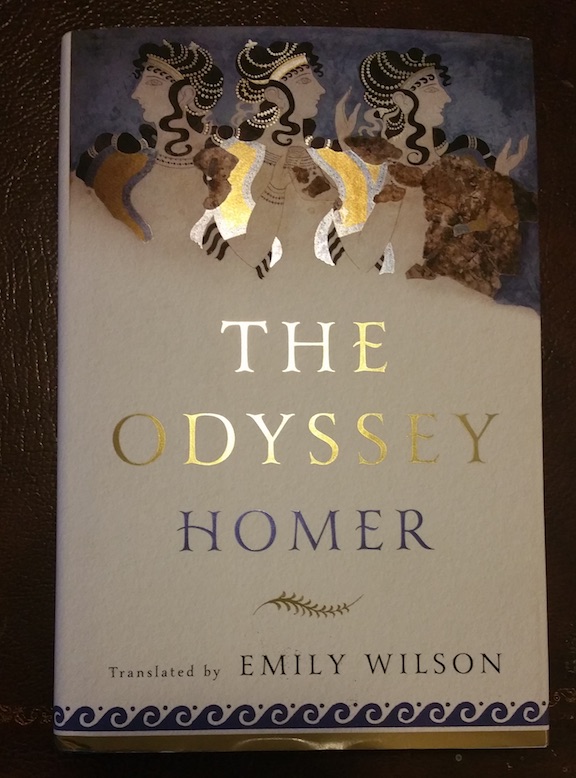

Whose story does the Odyssey tell? The answer seems obvious enough: from its first line, the eponymous epic tells the story of “the man of many turns” (as Albert Cook translated it), the story of “a complicated man” (as Emily Wilson translated it), the story of Odysseus, favored of Athena, goddess of wisdom.

But it tells many other stories too, and, much unlike the Iliad, which is a tale of men in conflict and companionship with other men, the Odyssey is very much a tale of men and women in conflict and companionship with one another. It is as if the pastoral world of human life awhirl upon the god-forged shield of Achilleus flowed through the poet’s voice and on its current carried the hero home, where everybody knows your name.

But it tells many other stories too, and, much unlike the Iliad, which is a tale of men in conflict and companionship with other men, the Odyssey is very much a tale of men and women in conflict and companionship with one another. It is as if the pastoral world of human life awhirl upon the god-forged shield of Achilleus flowed through the poet’s voice and on its current carried the hero home, where everybody knows your name.

Still, it is not just the story of Odysseus, the man, the husband, the father, the patriarch – it is the story of his family. There is the brooding, moody Telemachus, stewing in his frustration, angry at his mother, dangerously close to souring into Hamlet territory – tragic, yes, but not at all heroic.

And there is Penelope, wife of Odysseus and mother of Telemachus, beset by suitors who daily devour the wealth of Odysseus’s household as they attempt to “woo” Odysseus’s wife. If she is not a widow, she might as well be, for neither wise Mentor nor the few pious councilmen of Ithaca can protect Penelope from the many suitors’ incessant pestering—or if they can, they don’t. Meanwhile, Odysseus’s father, old Laertes, has secluded himself in grief for his lost son, while Odysseus’s son has yet to prove himself man enough to guard the safety of his mother.

The Odyssey is Penelope’s story too, and it reads so differently in this #MeToo moment.

Surviving in the patriarchy without a male protector is no easy task. In Odysseus’s long absence, Penelope is getting propositioned every day by men who don’t respect her agency. That’s what it amounts to. Penelope, within her own domestic sphere – the workplace of a Greek noblewoman – is enduring daily harassment as one man after another asks her to share his bed, to be his wife. But that’s not what she wants. She wants Odysseus back home, and she will wait – for eighteen, nineteen, twenty years – however long it takes.

This is why she has not returned to her father’s house. For to do so would be to admit that Odysseus is never coming home, to admit to widowhood, and thus to make herself marriageable.

So Penelope has the unenviable job of trying to persevere in a space she wants to hold open for her own future, and her family’s future. Her strategy for survival is to humor the “suitors” who daily proposition her without either yielding to them or refusing them outright. For as long as each man thinks he has some hope of having her, no man will allow another to take her by force. That is her only gambit.

The suitors seem to believe that she enjoys it – she enjoys being the object of their desire, the recipient of all their propositioning.

Antinous slut-shames Penelope to her own son:

“…She is cunning.

It is the third year, soon it will be four,

that she has cheated us of what we want.

She offers hope to all, sends notes to each,

but all the while her mind moves somewhere else.” (II, 90-95)

That bitch. She likes the attention, but she won’t put out.

Her very refusal makes her all the more desirable – a prize to win. What woman does not wish to be desired? And even if Penelope married at 14 or 15, she is an old matron now. In fact, she might be well into her forties, for she is on her twentieth year of waiting for her husband to come home. Is that what they want? Penelope the MILF

? Penelope as happy, taken Madame George?

They want Penelope for her mind. Each man among them wants to be the master and the center of her thoughts.

Antinous has enough self-knowledge to know that. He tells frustrated Telemachus,

“Athena blessed her with intelligence,

great artistry and skill, a finer mind

than anyone has ever had before,

even the braided girls of ancient Greece,

Tyro, Alcmene, garlanded Mycene –

none of them had Penelope’s understanding.

But if she wants to go on hurting us,

her plans are contrary to destiny.

We suitors will keep eating up your wealth,

and livelihood, as long as she pursues

this plan the gods have put inside her heart.

For her it may be glory, but for you,

pure loss. We will not go back to our farms

or anywhere, until she picks a husband.” (II, 116-129)

I read these lines, beautifully rendered by Emily Wilson, on the same day that I read The New Republic

‘s deeply researched, damning article, “A Professor is Kind of Like a Priest.” Using the recently publicized cases of Franco Moretti and Jay Fliegelman, both professors in the English department at Stanford, the essay explores how academics departments deal with the rumored or confirmed abusers in their midst.

In that essay you can read the details of how the English department at Stanford dealt with Fliegelman, who raped his PhD student, Seo-Young Chu. There were professors in that department who, when they learned of it, took action and brought the charge to the university’s administration. But there were professors in that department who closed ranks around Fliegelman:

Consent is slippery in a space as hierarchical as academia. Even if training for sexual assault prevention and awareness is strengthened, it will have to contend with a pre-existing culture defined by vastly unequal levels of power. On Fliegelman, [former Stanford PhD student James] Marino said, “It became immediately obvious to me that it was not to discuss this with faculty. It was clear that some faculty supported him very deeply—some were angry.” As one professor told him, “These are supposed to be the enlightened guys, but they stick together like the fucking mafia.”

When I read Marino’s observation, I immediately recognized the dynamic – not just at Stanford, but at every place in academe: enlightened guys who stick together like the fucking mafia to protect the privilege of predation. (The Chronicle, it seems, is seeking to crowd-source a list of capos and dons and embark on its own de facto Title IX investigations

.)

But what I found most striking in the article – and there’s much that’s striking in it, I assure you – was this paragraph:

That Fliegelman offered “genuine intellectual help,” that he had “professional skills,” that he was “brilliant,” as we heard from one former graduate student after another, reveals one of the tragic ironies of Fliegelman’s predatory behavior. Prospective academics were forced to choose between their careers, sense of ethics, physical safety, and psychological well-being, while the “brilliance” of predators in power often overshadowed the brilliance of those without it. Marino, who had been Chu’s peer at Stanford, observes that media accounts of her story rarely note that she “was arguably the brightest student” among the graduate students. “She had the edge over a bunch of really smart students,” [emeritus Professor Herbert] Lindenberger told us. “She was just brilliant.”

She was just brilliant. And instead of nurturing a brilliance that might some day outshine his own, Fliegelman sought to possess it – to possess her, the student with the liveliest mind, the student with the brightest future – for himself.

Athena blessed her with intelligence,

great artistry and skill, a finer mind

than anyone has ever had before…

In spite of what she suffered, Seo-Young Chu is brilliant still, and she has a brilliant future in academe.

Jay Fliegelman does not. He is forever tarnished, forever dimmed, forever overshadowed by his own penchant to possess and put down women who outshone him and outshine him still.

To the wise, the gods are just.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Beautiful!

It seems that Karen Kelsky (“The Professor Is In”) has created a crowdsourced google survey for those who would like to anonymously tell their stories of harassment in academe. This is quite different from the Chronicle survey, which invites people to share confidential information with the Chronicle but not with one another.

Here is a link to Kelsky’s survey:

Sexual Harassment in the Academy: An Anonymous Crowdsourced Survey

And here is a link to the results reported so far:

Responses to Survey (there are scrollbars within each question/response area to allow you to scroll through all responses for each question)

What we are witnessing, in real time, is the backchannel moving to the mainstream. Things might get a little messy, and academe does not handle messy well. But when 70% of your labor force is contingent, there’s not a lot of incentive to keep quiet for the sake of “the institution.” And there’s certainly no incentive to do so for those who were driven out of it entirely by this behavior.

This is an interesting moment.

I’ll respond with the letter I sent to the New Republic this morning and published on my blog, http://lefthandofeminism.com :

Dear Editors of New Republic,

Thank you for drawing attention to the pervasive sexism and abuse of power at universities and colleges in the article, “A Professor is Kind of Like a Priest.” I applaud Irene Hsu and Rachel Stone for noting that Seo-Young Chu’s, Jane Penner’s and my stories are neither “single instances of faculty sexual abuse,” but rather part of a “larger culture of silence and complicity, which has made for a dangerous, destructive, and exclusionary educational environment.” I have a few complaints about the way the article was edited.

First, a correction. The copy reads, “After the two went out to dinner one night, Moretti returned with Latta to her apartment.” This is inaccurate. I have no memory of having dinner with Franco Moretti, and cannot remember why he came to my Oakland apartment.

Second, your article omits one of the most egregious elements of my story, which I told to Hsu and Stone. This is the university’s utter indifference and cover-up of my complaint at the hands of Frances Ferguson, then the Title IX officer at Berkeley. Ferguson covered up for Moretti by actively discouraging me from making a formal complaint, which she described as a harrowing experience likely to induce as much trauma as I had already suffered. Ferguson was a member of the same department and knew Moretti well enough to recognize whom I was describing when I went to speak to her, yet she commanded, “Don’t tell his name.” Ferguson’s icy demeanor and departmental association with the man who raped me twice, plus the fact that she was then the only university officer to whom I could go with my complaint at the time, made it clear to me that I would receive neither sympathy nor support from the UC Berkeley. She was the cold and indifferent face of the institution. Ferguson’s cover-up and Moretti’s threat that, if I were to file formal charges against him, the wife of another colleague in the English department, a powerful lawyer, would defend him and that he would ruin my career, silenced me for many years.

Third, your article fails to indicate that this same Frances Ferguson, Walter Benn Michael’s wife, actively sought to recruit Moretti for a position at Johns Hopkins University, where she was also teaching in the 1990s. It was only graduate student outcry after Moretti molested a female graduate student during his interview that foiled Ferguson’s wish to bring him to campus.

Finally, the editor of the article insisted that its authors insult me by asking whether I believed that Franco Moretti raped me both times that I remember having unwanted sexual contact with him. I emphatically responded, “yes.” The article fails to mention this second rape, and therefore also neglects to tell the whole story.

I will publish this letter publicly on Facebook, just in case you are too timid to publish it as an editorial in New Republic, where it belongs.

In truth,

Kimberly Latta, Ph.D.

Wow. Thank you for telling your story so clearly. I believe you.

I believe you too. Thanks for sharing your letter.

LD: I’m so pleased you’ve relayed aspects of Wilson’s translation here. It’s making me nostalgic for my first reading of the Odyssey, nearly 22 years ago, or so. I remember my emotional sympathy for Penelope, and my thinking anew about all of those left behind due to the ravages of war. I wish I had more time to reread those Greek classics, given my intellectual changes over those years. – TL