Can you pray a country into existence? This idea refueled warsick colonists as they made bloody progress through the American Revolution. Certainly, young William Palfrey thought so. On New Year’s Eve, 1775, Palfrey and his fellow patriots huddled in Christ Church, across from the Cambridge Common, where George Washington had taken command of the ragged Continental Army just a few months earlier. A Boston merchant who toured London, Washington’s 34-year-old aide-de-camp found himself pressed into a number of new roles: soldier, paymaster, and, now, priest. Like his general, Palfrey worried about the daily tasks of war. Soldiers’ pay was mounting, the militias needed cohesion, and monthly expenses tallied $275,000. Palfrey and his friends had endured British occupation since spring, then a hungry winter. They were drained. Where could Palfrey and other worshippers pray to Providence, safely, in their city under siege?

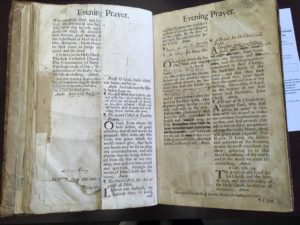

Many houses of worship were hollowed out by war. Boston’s Anglican clergy leaned loyalist, plunging into bankruptcy or pursuing Halifax exile. Acting at Martha Washington’s request, Palfrey opened Christ Church for a single night of worship. The church, like the community it held, was stamped by conflict. Colonists had fired wildly at it, protesting a British soldier’s funeral. Bullet holes blistered the foyer. Inside, few of the king’s gifts survived. The lead organ pipes that boomed out Handel’s hymns had been melted down for ammunition at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Rainbow-and-gilt vellum Books of Common Prayer, sent as part of King George II’s or George III’s startup kit with altar cloth to new colonial outposts, already looked battered and rare in 1776. Worse, those pages—well-rubbed from use and rippled with water stain—held what Palfrey and his friends now read as the wrong kind of words to use in asking God for aid.

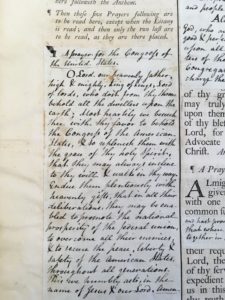

So, he edited. “What think you of my turning parson?” Palfrey wrote to wife Susannah. “I made a form of prayer, instead of the prayer for the King, which was much approved.” He deleted the centuries-old intercessions for monarchy. Rather, he led the improvised congregation in a prayer for Congress, calling on God to “be with thy servant the Commander-in-chief of the American forces.” Palfrey’s general, listening from the front pew as soldiers mustered hymns on bass viola and camp clarinet, appreciated the rewrite. The next day, Washington’s general orders spoke of the urgent need for “Subordination & Discipline (the Life and Soul of an Army) which next under providence, is to make us formidable to our enemies, honorable in ourselves, and respected in the world.” Editing the form of common prayer had reignited the “glorious cause.”

Church records tell us half the tale of how people “lived” religion while turning their hearts and minds to full-scale war. But modern revolutions run on reading material, and all books have biographies.* To get at early America’s shifting worship politics, let’s “track changes” in the Books of Common Prayer amended by Anglican and Episcopal laity in the 1770s and 1780s (shown here). As they changed ways of daily worship, Americans imprinted a new language of selfhood and statehood. They road-tested national rhetoric, long before they had any clear, constitutional vision of what that nation might look like. (For more, check out John Fea’s #ChristianAmerica? post, too). Parishioners moved around sacraments to suit new needs. The laity’s handwritten edits in prayer book margins—scraping off “King of Kings” and pasting over rote prayers for the royal family—operated as cultural cues for political change. At critical moments in the war, as colonists endured sieges and made sacrifices, they edited their prayer books to endorse turns in popular thought at the local level. During a holiday week when we think about declarations of independence big and small—and in a year marking the Protestant Reformation’s 500th anniversary—the humble prayer book still serves as a key intellectual artifact of revolution.

Church records tell us half the tale of how people “lived” religion while turning their hearts and minds to full-scale war. But modern revolutions run on reading material, and all books have biographies.* To get at early America’s shifting worship politics, let’s “track changes” in the Books of Common Prayer amended by Anglican and Episcopal laity in the 1770s and 1780s (shown here). As they changed ways of daily worship, Americans imprinted a new language of selfhood and statehood. They road-tested national rhetoric, long before they had any clear, constitutional vision of what that nation might look like. (For more, check out John Fea’s #ChristianAmerica? post, too). Parishioners moved around sacraments to suit new needs. The laity’s handwritten edits in prayer book margins—scraping off “King of Kings” and pasting over rote prayers for the royal family—operated as cultural cues for political change. At critical moments in the war, as colonists endured sieges and made sacrifices, they edited their prayer books to endorse turns in popular thought at the local level. During a holiday week when we think about declarations of independence big and small—and in a year marking the Protestant Reformation’s 500th anniversary—the humble prayer book still serves as a key intellectual artifact of revolution.

At the same time, these volumes were signs of consensus and communion in the Atlantic World. Books of Common Prayer first reached America’s shores alongside the earliest settlers. Often, the 1662 edition printed by London’s John Baskerville was formally issued to new American churches by the Royal Wardrobe. At Old North Church in Boston, vestrymen of 1733 opened a green-baize lined trunk mailed “from the Jewell Office.” Next to sterling silver communion plate, velvet pulpit cushions, and a Bible emblazoned with the royal arms, lay a second cache. Old North vestry received two prayer books, “bound in Turkey leather strung with blue garter ribbon and trimmed with gold fringe” and a dozen more for the community to share, all “bound in Calf Gilt & filleted & strung with blue Ribbon.” Prayer books were more than highly prized signals of royal favor. These worship aids consolidated five liturgical texts: daily offices, Litany, Holy Communion, pastoral offices, and the ordinal. As Rowan Williams suggests, the Book of Common Prayer outlines theological positions, but it is “less the expression of a fixed doctrinal consensus… more the creation of a doctrinal and devotional climate.” Across the Atlantic World, Anglo-American clergy used them to convey a community’s civilization, and learning. In fractured parishes, buying prayer books was often the sole purchase that everyone agreed on.

In the war’s early years, lay readers like William Palfrey filled pulpits and edited prayers. The paymaster’s prayer trended quickly. By May 1776, Baltimore officials struck out prayers for the king. Maryland’s faithful, one newspaper reported, “cannot with any sincerity of heart pray for the success of his arms…until our unhappy differences are ended.” In Boston’s Anglican quartet (Old North, King’s Chapel, Christ Church, and Trinity), readers pasted over royal prayers and scribbled in patriotic edits. “Sovereign” became “servant,” and “wealth” became “prosperity.” Pastors scratched out a common biblical refrain—“King of kings, lord of lords”—likely because of its royalist imagery. The “Kings Majesty” became “the President of the United States.” Worshipers prayed for divine guidance to bless “Congress” and “civil authority,” rather than the “lords of Parliament.” Patriot editors underlined the idea of civil religion found in Judges 21:25: “In those days there was no king in Israel, every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”

In the war’s early years, lay readers like William Palfrey filled pulpits and edited prayers. The paymaster’s prayer trended quickly. By May 1776, Baltimore officials struck out prayers for the king. Maryland’s faithful, one newspaper reported, “cannot with any sincerity of heart pray for the success of his arms…until our unhappy differences are ended.” In Boston’s Anglican quartet (Old North, King’s Chapel, Christ Church, and Trinity), readers pasted over royal prayers and scribbled in patriotic edits. “Sovereign” became “servant,” and “wealth” became “prosperity.” Pastors scratched out a common biblical refrain—“King of kings, lord of lords”—likely because of its royalist imagery. The “Kings Majesty” became “the President of the United States.” Worshipers prayed for divine guidance to bless “Congress” and “civil authority,” rather than the “lords of Parliament.” Patriot editors underlined the idea of civil religion found in Judges 21:25: “In those days there was no king in Israel, every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”

Only one person—the British sovereign—retained the copyright to the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. When American parishioners recited intercessions, they reiterated a shared hierarchy of social concerns. They reified an English heritage of state-sponsored spiritual welfare. Over the centuries, they made some minor alterations to the wording: noting newly-born sovereigns, or inserting providential pleas to end drought or illness. Anglo-American Protestants boasted a long line of doctrinal editors, after all, stretching back to the Reformation. Prayer book changes were normal. But such changes came at general conventions, after major clerical votes—not at the hands of lay readers operating an ocean away, minus an archbishop. The Revolution’s worship politics accelerated that change. Pew by pew, we see the moment when Americans turned away from a king, and toward a new country. What kind of faith would push them on?

Only one person—the British sovereign—retained the copyright to the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. When American parishioners recited intercessions, they reiterated a shared hierarchy of social concerns. They reified an English heritage of state-sponsored spiritual welfare. Over the centuries, they made some minor alterations to the wording: noting newly-born sovereigns, or inserting providential pleas to end drought or illness. Anglo-American Protestants boasted a long line of doctrinal editors, after all, stretching back to the Reformation. Prayer book changes were normal. But such changes came at general conventions, after major clerical votes—not at the hands of lay readers operating an ocean away, minus an archbishop. The Revolution’s worship politics accelerated that change. Pew by pew, we see the moment when Americans turned away from a king, and toward a new country. What kind of faith would push them on?

By fall 1783, clergy and laity drafted an American “Proposed Book” of Common Prayer. Their early efforts drew sharp criticism. The line edits were creedal, inflaming the British bishops then weighing whether to consecrate American clergy. The Nicene and Athanasian Creeds had been excised. William Palfrey’s form of prayer, which had grown popular during the war, stuck. “The Litany is much shortened, and adapted to the present reigning powers, and their state of government, instead of King and Parliament, ” the Connecticut Journal wrote approvingly. Internal dissent, however, doomed the “Proposed Book” before it took off into wider use.

By fall 1783, clergy and laity drafted an American “Proposed Book” of Common Prayer. Their early efforts drew sharp criticism. The line edits were creedal, inflaming the British bishops then weighing whether to consecrate American clergy. The Nicene and Athanasian Creeds had been excised. William Palfrey’s form of prayer, which had grown popular during the war, stuck. “The Litany is much shortened, and adapted to the present reigning powers, and their state of government, instead of King and Parliament, ” the Connecticut Journal wrote approvingly. Internal dissent, however, doomed the “Proposed Book” before it took off into wider use.

Gathering in a general convention that mirrored their federally minded colleagues in Congress, Americans issued an edition in 1789. Once they began editing the Book of Common Prayer, Americans found it hard to stop. In 1792, they appended guides for ordination. Extra edits in 1804 and 1808 redefined the pastor’s relationship with his flock, though the 1789 edition held (fairly) firm until 1880. By 1908, George III’s elegant, pigskin-bound gifts popped up in rare book auctions for $20 to $25. Or you could buy Hall & Sellers’ first edition of the American version, printed in Philadelphia. Once a battleground for independence and the interpretation of religious liberty, by the American Century’s dawn, both prayer books sold for the same price.

*Thanks to panelists Sam Haselby, Benjamin Park, and Roy Rogers, for expanding my views on this topic since I presented it at the American Historical Association in Denver, Co., Jan. 2017.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

What a marvelous post. Beautifully written — and fascinating.

I found this very intriguing: changing the wording from “wealth” to “prosperity.” I’d love to know more about what prompted that particular change.

Also, I’m wondering if the sense of freedom to change the BCP was something that accelerated as the war — and the new nation — continued on. In other words, do we see just a few cautious emendations at first, but then everything sort of picks up speed as people reshape the liturgy to suit their needs and moment, or do we see a kind of constant drip-drip-drip of small but significant changes that add up to a major reworking of the prayers and collects?

Thanks, LD, great comment! The question of “who” is the author behind the change blurs a bit, to be sure, in the historical record. When it comes to wealth v. prosperity, that particular edit has me thinking about work on Protestants and the market (i.e. Daniel Walker Howe, Mark Noll, Charles Sellers, Jefffrey Sklansky). As for the frequency and scale of change: Royal intercessions are first to go, and they ripple through the colonies as the war continues. As of 1789, Americans are urgent to construct Episcopal architecture, and build their own BCP. A big theological shift comes, I think, with the implementation of an approved process in place for ordination of American clergy (i.e. Samuel Seabury & co.). I wouldn’t mind a research trip to lovely Lambeth Palace Library and area to learn more about the British side of the story, and widen it beyond the North American view gloss’d here.

This is fascinating. Of course another important factor was that the Scottish bishops who ordained Samuel Seabury bishop in 1784 asked the Americans to use their sequence of prayers at communion,wnhich shifts several prayers to before the Eucharist. (And Seabury turned to the Scottish bishops because he would not take the oath to the king, acknowledging royal supremacy.

Yes, exactly! Thanks for pointing out the ordination aspect of this story, likely deserves a separate post. Seabury earned important support from across the pond: John Adams, John Jay, John Moore, Benjamin Franklin, and Granville Sharp were all involved in the effort to secure Episcopal ordination, sort of a “cultural diplomacy” initiative that they took up jointly in the wake of sealing a difficult peace. Would be interesting to contextualize further the intellectual project of establishing American religious authority in more of a global context in the revolutionary 1780s and 1790s, following up on the recent work of Spencer McBride and others. Thanks for the idea!