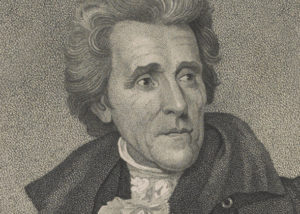

The adoption of Andrew Jackson as a sort of icon and model by Donald Trump left me wondering more generally about the ebbs and flows of Jackson’s reputation over the years. I’ve been doing some reading and some writing about it, and this bit is something I decided against using in that writing project but which I thought might be of some interest here.

The adoption of Andrew Jackson as a sort of icon and model by Donald Trump left me wondering more generally about the ebbs and flows of Jackson’s reputation over the years. I’ve been doing some reading and some writing about it, and this bit is something I decided against using in that writing project but which I thought might be of some interest here.

Jackson’s reputation among writers of history was abysmal throughout the nineteenth century. Even his most sympathetic biographer, James Parton, believed him wholly inadequate to the Presidency’s intellectual and temperamental demands. “I find in General Jackson’s private writings,” Parton concluded, “no evidence that he had ever studied the art of governing nations, or had arrived at any clear conclusions on the subject […] Unapproachable by an honest opponent, he could be generally wielded by any man who knew how to manage him, and was lavish enough of flattery.” Parton did not, however, see Jackson as a demagogue but rather as a real man of the people, embodying their vices of ignorance and irascibility but truly understanding the underlying principle of democracy: “He had a clear perception that the toiling millions are not a class in the community, but are the community. He knew and felt that government should exist only for the benefit of the governed… that the rich are rightfully rich only that they may so combine and direct the labors of the poor as to make labor more profitable to the laborer.” Jackson’s election and re-election was a misfortune, then, but not a crime—Jackson, he decided, “appears always to have meant well.”

More culpable, in Parton’s opinion, were the unscrupulous forces behind Jackson, who lacked his feeling for the “toiling millions,” and the forces arrayed against Jackson, who in their aristocratic condescension toward democracy offered the people no better alternative. Parton strongly condemned the “spoils system” of political patronage that Jacksonians greedily implemented, but he had especially harsh words for the ineffectual elite who opposed Jackson: “as a general rule, the educated American of leisure has been the most aimless and useless of human beings.” It was these groups—and not Jackson or the ordinary men whose votes carried him to the White House—whose responsibility it was that “the public affairs of the United States have been conducted with a stupidity which has excited the wonder of mankind.”

A major shift occurred beginning in the late nineteenth century. As history emerged as a profession and an academic discipline, the origins of its practitioners changed as well: there were more who grew up west of the Alleghenies and in middle class homes. This demographic revolution was symbolized most of all by Frederick Jackson Turner, whose 1893 paper “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” caused a fundamental reorientation of the discipline and even of American identity. Turner, a native of Wisconsin, looked to the internal environmental conditions of the American continent as the determinative influence on the nation’s institutions and character rather than the transatlantic heritage of what had been transplanted from Europe. This viewpoint changed the shape of U.S. history. No longer was the Jacksonian era a moment when the wisdom of the Founders’ Enlightenment ideals of rational government failed before an onslaught of rude mobocracy; instead, Jackson’s election advanced the Founders’ promises of self-rule as a birthright for all Americans.

In celebrating the Jacksonian upsurge of democracy, Turner failed to emphasize the stark limits remaining on even the most basic civil rights, as they remained restricted to a population far less than half of the whole nation. What Turner did emphasize was geography: the expansion of the electorate leading up to Jackson’s 1828 electoral victory included not just the removal of property qualifications for white men in some states, but even more importantly the “Rise of the West,” as Turner titled his monograph on the 1820s. The “Western” frontier states—what we now call the Midwest—entered the Union without property qualifications: evidence for Turner of his argument that the tide of freedom flowed from West to East. Turner and his innumerable disciples treated Jackson as the archetypal Westerner; his election was the West’s triumph over the East.

Yet Turner’s understanding of Jacksonian democracy was more complex than this regional binary allows. Turner sought to rehabilitate Jacksonian democracy not just by valorizing what he saw as its Western origins but also by overturning the nineteenth century’s snobbery toward partisanship, which Parton and so many others decried as the legacy of Jackson’s spoils system. It is worth noting that Turner’s middle name was a tribute to his father, Andrew Jackson Turner, a big wheel in—ironically—the Republican Party of Wisconsin. Young Fred Turner tagged along often as his father canvassed the vote and served the party line with dogged and sometimes underhanded loyalty. For instance, his father was rumored to have clinched a local election for the GOP by hurrying in sure Republican voters early in the morning and then sending a man who had recently recovered from smallpox to loiter in the doorway of the polling place, driving away undecided and Democrats who had yet to vote.

Some of Turner’s acolytes offered less colorful but more convincing defenses of the party as a crucial democratic institution. Carl Russell Fish’s 1904 study The Civil Service and the Patronage coolly defended the spoils system as the only way the financial costs of extending democracy could have been met. If politics was meant to include men who needed an income, then the only way democratic leaders could support the inclusion of those men was to give them a job—and the civil service was the only place to do that. Fish’s work also included a tribute to Jacksonian democracy titled The Rise of the Common Man, 1830-1850, which was perhaps the most influential work tying that phrase to Jackson and his era.

But what historians and others meant when they linked Jackson to the “common man” was never totally straightforward. What was certain was that no one in Jackson’s own time associated him with that phrase—at least not positively. In a eulogy delivered in 1845, one Jacksonian examined his record as a “politician, rising regularly, through every gradation of office, from that of district attorney to the presidency of the United States” and demanded, “is there not evidence enough to convince all, that he whose memory we this day honour was no common man? No! He was an uncommon man.” It was only after Turner had begun using the phrase “common man” honorifically as a term exemplifying the democratic spirit that it became attached to Jackson.

For Turner, the “common man” was primarily an agrarian and mercantile figure, but others quickly extended it to the growing urban proletariat of the 1820s and 1830s. Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. was among the first to do so, but he did not regard the “rise of the common man” as identical to what we could call “the making of the American working class.” Perhaps a better synonym could be found in the title of a later Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the era, by Alice Felt Tyler: Freedom’s Ferment. In a brief essay with the Turnerian title “The Significance of Jacksonian Democracy,” Schlesinger, Sr. linked the eruption of the new labor movement to the intellectual restlessness which produced James Fenimore Cooper and Ralph Waldo Emerson and to the moral agitation which ignited men like William Lloyd Garrison and experiments like Brooke Farm. Quoting the poet James Russell Lowell, he decided that the age “was simply a struggle for fresh air, in which, if the windows could not be opened, there was danger that panes would be broken.”

For Schlesinger, Sr., this struggle for fresh air came “from below,” but not necessarily from the bottom up: it characterized the middle ranges of society as much or more than it did the nation’s downtrodden. What was most important was that the energy of the era could not be traced back to its leading figures, not even to Jackson. “The choice of Andrew Jackson or of a man like him was almost inevitable under the circumstances. The popular demand was for a president who should symbolize the apotheosis of the common man,” Schlesinger, Sr. wrote. Jackson “was possible because the times had prepared the way for his coming and had ripened the popular mind for his message.”

Writing in 1922 after the election of Warren G. Harding (who was elected, many said, simply because he looked like a President), Schlesinger, Sr. may have been subtly encouraged to overstress the mood of the era in accounting for Jackson’s election. But the more substantive point was that Jackson was not the real leader of the democratic movement: no single person was. Instead, we must look again to collective actors like parties and like the labor movement—and even there we are redirected back not so much to labor politics but to party politics. For Schlesinger and certainly for the historian and Democratic political operative Claude Bowers, the significance of the emergence of a “Working Men’s Party” in Philadelphia in 1828 was not so much the emergence of the “Working Man” as a political force but the maturation of the “Party” as a democratic instrument.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

how could they take him down. the people in new Orleans must not know what there doing !!!!!!

Interesting that this assessment stops before it gets to Harry Watson, Robert Remini, and Sean Wilentz, the varsity cheerleaders of AJ.