Like last week and Andrew Hartman’s wonderful post, today I am posting the paper I gave at the African American Intellectual History Society. Some of this will seem familiar to readers of this site, but it is my first crack at what I hope to be the beginning of the second, post-dissertation project I shall begin working on over the summer. Meanwhile, AAIHS has begun publishing a re-cap of the conference–my reflections on it will be posted on their website later this week. Enjoy!

The plight of the black South as an intellectual center was on the mind of Vincent Harding when he wrote a nuanced and otherwise appreciative review of Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual in 1968.[1] Cruse’s book, released the previous year, set off an avalanche of both praise and criticism amongst leftists of all racial hues and ideological dispositions. Harding, a confidant of Martin Luther King, Jr. and a Southerner, noticed an unfortunate omission from Cruse’s magnum opus. “His single-minded focus on Harlem,” wrote Harding, “eliminates treatment of that crucial group of black intellectuals who have operated in the South for the last decade, and who have much to do with the latest resurrection of blackness.”[2] For Harding, forgetting about the African American South was a mistake which threatened to erase not only an entire region of the nation—not to mention the experiences of millions of African Americans—but also damage the growing intellectual ferment of a resurgent African American radical tradition.

My paper, “Where Did We Go From Here: Black Radicalism and Southern Identity,” argues that the Black Left—long a stalwart of campaigns for civil and human rights in American society—was important to the debate over Southern identity in the immediate post-civil rights era. They helped make sense of a region that was home to most African Americans and was transitioning from a place of Jim Crow segregation to a region that offered new hope for most blacks. The South was not perfect. But African American  radicals often pointed out, through the twentieth century and the so-called “Long Civil Rights Movement,” that all regions of the United States had severe issues with anti-black racism.

radicals often pointed out, through the twentieth century and the so-called “Long Civil Rights Movement,” that all regions of the United States had severe issues with anti-black racism.

For black radicals, the South offered a way for them to critique various groups: conservatives and the American right wing, resurgent after 1965; liberals, black and white, who they often criticized for not being strong enough on anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and anti-imperialist politics; and white radicals, who they also argued against for their own blindness on issues of race. By writing and speaking about the South, black radicals could use a region often seen as separate from the rest of the United States and argue, on the contrary, that the region was the id of American politics and culture. This was also true of seeing the South as the heart of African America—reminding Northern and Western blacks, for example, of the centrality of the South to the African American experience.

By studying publications such as The Black Scholar, The Negro Digest/Black World, and Freedomways, we can get a better sense of how Black radicals added to the discussion of changing Southern identity that broke out as soon as the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Acts were passed by Congress. No longer could the South be defined by racism alone. But what did this mean for conceptions of the American South in not just the American, left, or Black mind, but in the minds of African American radicals? Answering this question means understanding the relationship between the Black left and larger, “mainstream” African American publications such as Ebony and Jet, which played a pivotal role in defining African American debates in the public sphere in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Such a study, inevitably, means not just reading the journals of the Black left but reading mainstream Black publications and wrestling with the legacy of Lerone Bennett. A historian by trade, Bennett’s editorship at Ebony during the 1960s and early 1970s was a watershed for popular history in an American publication.[3] But Bennett also used his space in Ebony to talk about the new relationship between African Americans and the American South. He also gave space to other African American writers to talk about this recent development in American history. These writers were essential to re-imagining what the South could be.

While not defining Bennett specifically as a radical, it is important to see how his writings and speeches in the 1960s and 1970s gave a prominent platform to potentially radical thought within the larger African American mainstream. His provocative essay on the idea of “liberation” in the August 1970 issue of Ebony, for example, recalls how for many African Americans encountering “radical”—or at the very least, non-liberal—ideas in  popular magazines was nothing new.[4]

popular magazines was nothing new.[4]

Liberation was something beyond the traditional “integration” or “separation” dichotomy that purportedly dominated discourse among African Americans since emancipation and the end of the American Civil War. Bennett described America as an “illusion,” and believed African Americans would do well to remember this when debating the fate of the country.[5]

For radical African Americans, the South was useful in terms of talking about several major issues in American political economy. The rural South dominated a significant amount of discourse among black leftists in the second half of the twentieth century. Recovering the ways in which they talked about the rural should remind all of us that rural America has not disappeared. Today, the rural is often only invoked to talk about the idea of the “white working class” but black radicals always recognized that African Americans were still living on the land, especially in the Deep South.

Second, the importance of black culture to black radicals’ ideas of the American South cannot be understated. Time and again after the 1960s, black radicals argued that the South had to be remembered as another site of cultural production. Expressing concern with the Northern, and urban-heavy, focus of the Black Arts Movement of the 1970s, black radicals in the 1970s and beyond cautioned against forgetting about the South in the development of modern black culture.

Black radicals also never shied away from putting the American South in an international context. Tying the South to the nation and the world, African American leftists argued that knowing more about the South meant coming to grips with its ties to the world—through trade, culture, and intellectual bonds. Doing this helped to avoid falling into the traps of “American” and “Southern” exceptionalism that plagued so many others when discussing problems in American society. It also gave black radicals reason to believe that their struggle on behalf of African Americans was part of a larger, worldwide struggle against oppression.

Finally, memory played a critical role in how African American radicals saw the South, and how they argued it was important to a larger conception of American society. A radical memory of events such as the American Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Civil Rights Movement were all important to radicals trying to conceive of a different Southern United States. Memory has always been a political project—perhaps the most political of any aspect of a public sphere. Radicals understood this. For them, understanding a radical Southern past meant creating new alternatives for the future.

In 1977, Black Scholar magazine, a journal dedicated to African American radical issues, devoted its May issue to “The Black South.”[6] With a weathered African American female farmer on the cover, The Black Scholar gave considerable space in this issue to brewing debates about what it meant to be an African American Southerner in the 1970s. Dealing with the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement, and the rise of a colorblind conservatism that promised to make further civil rights advances harder, “The Black South” offered a window into late 1970s African American radicalism’s views of the South. Such a view represents a larger tradition, of the African American left attempting to create a new narrative of the future by re-evaluating the history and traditions of the country’s most oppressive region.

“The Black South” combines some of the themes established in this paper that define the ways in which black radicals viewed the American South. For example, an essay by Manning Marable combines a look at black Southern politics with a critique of the African American middle class. Marable argued that what was going on in Tuskegee and across the South in the late 1970s—the rise of a successful, but small, African American middle class into prominence in politics and economics, and the concurrent clamp down on black popular politics—was both a replay of the previous century’s post-Civil War Southern  history and a reflection of larger trends across the African Diaspora. It was a “pattern…familiar to the pan-African scholar of the Caribbean and neocolonial Africa: electoral political power is placed by the white elite into the hands of the black petty bourgeoisie, popular political participation of the black masses declines, corruption is institutionalized, police and law enforcement officials increase in number, black culture becomes a ‘tool for class rule,’ and the history of pre-independence movement is deliberately distorted.”[7]

history and a reflection of larger trends across the African Diaspora. It was a “pattern…familiar to the pan-African scholar of the Caribbean and neocolonial Africa: electoral political power is placed by the white elite into the hands of the black petty bourgeoisie, popular political participation of the black masses declines, corruption is institutionalized, police and law enforcement officials increase in number, black culture becomes a ‘tool for class rule,’ and the history of pre-independence movement is deliberately distorted.”[7]

Here, Marable uses several hallmarks of black leftist critique of the South to make his larger points. He both links the current events of Southern politics and culture to the region’s past, while also noting international trends within which these events fell. Marable referred to the politics of the post-civil rights South as a “politics of illusion.” He argued that the talk about a “New South” that was then prevalent across the South—never mind across the nation—cloaked deep problems in Southern society in regards to race and class. Marable criticized what he believed to be a class-based alliance between the “black petit bourgeoisie” and prominent white Tuskegeeans who were, not long ago, segregationists. That Marable chose Tuskegee as his stand-in for the American South is not surprising, considering that ten years before Stokley Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, in Black Power, argued that the city offered a good example of growing black political power in the South. Not so, argued Marable—such power, in his estimation, had already proven to have severe limits ten years after the release of Black Power.

In the same issue, Charles H. Rowell, a professor of literature and prominent African American literary editor, wrote a critique of the Black Arts Movement. Attempting to rescue the black Southern artist from obscurity, Rowell argued that these writers were “more than our brothers and sisters in the North, are closely fixed to our roots.”[8] Developing a proper and full “Black Aesthetic” required developing a deeper understanding of the Black South. In fact, Rowell’s essay was a riff off an Addison Gayle essay written in the September 1974 issue of Black World, where he also lamented the lack of a black Southern voice in the Black Arts Movement. Gayle noted the irony that most writers associated with the “Black Aesthetic” were, in fact, from the South. Yet they barely wrote about the region. Gayle argued that this was due to the “Black Aesthetic” being “an urban phenomenon, pushed into actuality by the Black Power Movement of the 1960s to serve as the cultural arm of the Black Nationalist Movement.”[9]

Gayle noted a prominent theme here in radical critique of the Black South—the need to understand the rural South as paramount. Even in an urbanized, industrialized America, the rural South remained the site of political, economic, and cultural struggle for African Americans. Writers in places such as The Black Scholar noted with concern the collapse in black ownership of the land in rural South.[10] At the same time, other groups also noted the importance of the rural South in a broader conception of the future of African Americans. The Black Radical Congress, an organization of African American leftists that organized in 1998, recognized the centrality of the rural South to the Black Freedom Struggle. In their “Freedom Agenda,” promulgated in 1999 at their National Council in Baltimore, Maryland, the BRC pointed to the South as a key part of their larger, international fight against capitalism and anti-black racism:

“More than 50 percent of people of African descent residing in the U.S. live in the South, where workers’ earnings and general welfare are besieged by corporate practices, and where “right to work” laws undermine union organizing. Thus, we seek relief for Southern workers from corporate oppression, and we will struggle to repeal anti-union laws. We will also fight for aid to Black farmers, and for the restoration of farm land seized from them by agribusiness, speculators and real estate developers.”[11]

In the statement, the BRC acknowledged the fact that most African Americans lived in the American South. They linked the problems of black workers in the region to those of all workers—seeing problems such as “right to work” and lack of strong unions in the region as crippling the power of all workers in the South. In addition, the BRC reminded its members of the rural South, and the importance of Black farmers to the economy.

The African American left also repeatedly used memory of events in the history of the South as a way to speak to current issues about racism. This use of memory had several uses. The Black Left, by calling back to Reconstruction or the Civil Rights Movement, could ground activists in a longer tradition and give them examples to look back to. Further, black leftists and radicals often used memory of events to put the South in an international context. This made it clear to activists that they were not alone in their struggle.

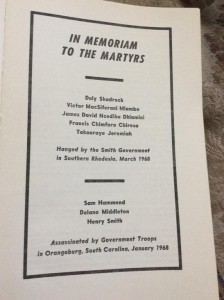

For example, the editors of Freedomways often used their magazine to link past struggles to contemporary black leftist movements, as well as linking those current campaigns to radicalism around the world. Their Spring 1968 issue—dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr. in the aftermath of his assassination—included a tribute to a far less  heralded group of African American martyrs. In January 1968, three African American men—Sam Hammond, Delano Middleton, and Henry Smith—were murdered by South Carolina Highway Patrol officers in Orangeburg, South Carolina on the campus of South Carolina State College. Freedomways honored the three men by including them in a larger tribute to “martyrs” against anti-black racism. Their tribute was on the same page as the names of five men executed by the white supremacist government of Ian Smith in Southern Rhodesia. For Freedomways editors, who were part of a longer tradition of black radicals linking the local to the international, they were all freedom fighters against white supremacy.

heralded group of African American martyrs. In January 1968, three African American men—Sam Hammond, Delano Middleton, and Henry Smith—were murdered by South Carolina Highway Patrol officers in Orangeburg, South Carolina on the campus of South Carolina State College. Freedomways honored the three men by including them in a larger tribute to “martyrs” against anti-black racism. Their tribute was on the same page as the names of five men executed by the white supremacist government of Ian Smith in Southern Rhodesia. For Freedomways editors, who were part of a longer tradition of black radicals linking the local to the international, they were all freedom fighters against white supremacy.

Black radical feminism has also benefited from looking to the past for modern-day political struggle. Recall that the Combahee River Collective named itself after an event in the American Civil War. Harriet Tubman’s liberation of over seven hundred slaves in South Carolina during the Combahee River Raid in 1863 was a dramatic moment in that conflict.[12] The Combahee River Collective’s use of that term was a callback to not just African American resistance to slavery, but to situating themselves as part of a distinctly African American womanist tradition of fighting the twin oppressions of racism and sexism.

Black radicals conceived of the South as being a key battleground in the struggle against international white supremacy and capitalism. The South, as conceived in the mind of Black radicals, was as important as any other place in the United States or the world. The larger project currently being researched looks at the twentieth century black radical and her relationship to U.S. South.

[1] Vince Harding, “Beyond the Black Desert,” Motive, March 1968, p. 45-48.

[2] Harding, 47-48.

[3] Insert citation for articles on Bennett at Ebony by James West.

[4] Lerone Bennett, “Liberation,” Ebony, August 1970, p. 36-43.

[5] Bennett, 43.

[6] “The Black South,” The Black Scholar, May 1977, Volume 8, Number 7.

[7] Manning Marable, “Tuskegee and the Politics of Illusion in the New South,” Black Scholar, May 1977, p. 24.

[8] Charles H. Rowell, “Diamonds in a Sawdust Pile: Notes to Black South Writers,” Black Scholar, pg. 26.

[9] Addison Gayle, “The Black Aesthetic 10 Years Later,” Black World, September 1974, p. 21.

[10] Leo McGee and Robert Boone, “Black Rural Land Decline in the South,” The Black Scholar, May 1977, pg. 8-11.

[11] “The Freedom Agenda,” Black Radical Congress, April 17, 1999, http://eblackstudies.org/brc/aboutus/freedomagenda.html, accessed on January 31, 2017.

[12] “Combahee River Collective,” http://www.blackpast.org/aah/combahee-river-collective-1974-1980, accessed February 1, 2017.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is a very nice piece. Thank you.