This past Thursday and Friday, I enjoyed the warm hospitality and vibrant intellectual company of professors and students at Louisiana Tech University. The historians at Tech host an “International Affairs” speaker series every year; this year their theme is “America and the World in the Age of Trump,” and they kindly invited me to participate.

A few weeks ahead of the event, I sent a title for my talk to Drew McKevitt, one of my marvelous hosts, so that he could pass it along to the student who would be designing the poster. My title was, “Toward a Correct History of ‘Political Correctness.’” Here’s the poster for the event:

When I saw that poster, I said, and I quote, “Holy shit.”

I mean, that is one provocative image.

Right up to the moment that I started to speak on Friday, I was pretty worried that what I had planned to talk about and how I planned to approach the subject just wouldn’t measure up to the expectations prompted by this image, in terms of controversy or boldness or political critique. But the talk went well, and it was well received. I got to throw a little shade at Stanford (more on that below) and at the people who are continually invoking some version of the canon wars or the abandonment of “Western Civ” or the rise of “political correctness“ as a pivotal moment of cultural declension.* The problem, of course, is what people are trying to do with that already problematic narrative: delegitimize and defund traditional institutions of higher education, turning what was once viewed as a public good into a private financial burden, while at the same time figuring out ways to turn a profit from the public’s distrust.

The Q&A afterwards was lively, it seemed to me, with a number of students challenging some of my stated and unstated assumptions about higher education as a public good. Every student who posed a question or made a comment was thoughtful, courteous and marvelously sharp. The next time I give a talk on this topic, I will be sure to build in those questions and my (revised) answers to them in the presentation itself. So many thanks to the Louisiana Tech students whose polite skepticism will make future iterations of my argument sharper and better.

Now, about that shade…

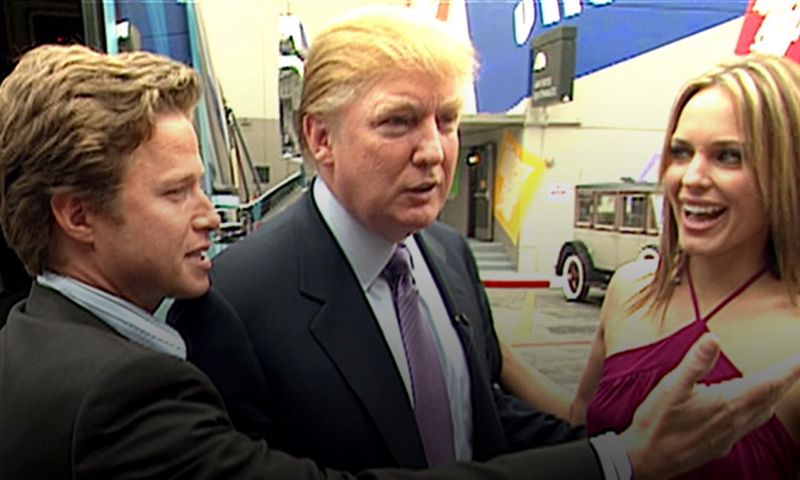

As it happened, while the bold poster advertising my talk was hanging in the hallways at Louisiana Tech, Stanford University managed to embroil itself in a controversy over the use of an old photo of the current President on a poster for an upcoming conference at the Law School. The title of that conference, much like the title of the speaker series at Louisiana Tech, posits the advent of a new age, the “age of Trump.” The conference, organized by Michele Landis Dauber, is called “The Way Forward: Title IX Advocacy in the Trump Era,” and the image Dauber wanted to use was this screengrab from Trump’s Access Hollywood interview with Billy Bush:

You can read the various rhetorical contortions of Stanford administrators’ successive findings and backtrackings in the Inside Higher Ed article linked above. The laughable rationale offered by the administrators who first denied Dauber permission to post the image on the Law School website or distribute it on posters advertising the event was that “these Access Hollywood images could give the appearance of partisanship” – as if the title of the conference had not already posited some potentially problematic connection between sexual harassment and Donald Trump.

My suggestion to the students at Louisiana Tech was that perhaps Stanford has a political correctness problem: it is apparently policing the speech of professors to make sure they do not say anything that might be construed as offensive to anyone.

What I didn’t mention to the Tech folks was the history behind Stanford’s current, diffident assertion of official nonpartisanship — nonpartisanship for some. That history has to do with the vexed relationship between the University and the Hoover Institution. (George Nash touches on some of this history in his book on Herbert Hoover and Stanford.) After a series of controversies in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, controversies which involved faculty insisting that a too-close association with the politically partisan Hoover Institution was jeopardizing Stanford’s reputation as a research university that fostered independent intellectual inquiry, the university apparently (and, some would say, belatedly) settled on its current policy.

And even in its backtracking, Stanford is standing by that policy, which basically boils down to the insistence that faculty speech must be apolitical. Of course, this policy doesn’t apply to Hoover Fellows when they are writing or speaking under the aegis of that institution, though the Hoover Institution itself may have other expectations regarding what sorts of political speech would be out of bounds for the scholars and public intellectuals affiliated with it. It is quite unlikely that those expectations overlap with the expectations of Stanford University for its faculty. Indeed, much of the work of the Hoover Institution is unabashedly, designedly political.

So, in effect (if not in intention), this insistence on neutrality or nonpartisanship, allegedly a long-standing policy of Stanford University, ends up protecting the political speech of conservative intellectuals on campus while muffling the political speech of liberal or Left intellectuals on campus.

Now, tell me again: who won the campus culture wars?

_____

*See, for example, David Brooks’s most recent execrable column (as opposed to his “most recent, execrable column”). This kitchen-junk-drawer-full of non-sequiturs was not on my radar screen yesterday morning, but it typifies the broader genre of jeremiads blaming every national and international problem on the revision of somebody’s syllabus.

23 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

We talked a little bit about current free speech controversies at Berkeley in the Q&A at LA Tech. I just ran across this reporting from Huffington Post on comments by Bernie Sanders & Ralph Ellison re: their views on no-platforming. It will be interesting to see whether this perspective has some wider influence in the current moment.

Bernie Sanders Condemns Threats Against Ann Coulter Speech At Berkeley

Glad it went well!

For my part, for my next book project on anti-intellectualism (broadly defined), I’m toying with the idea of including PC. It’ll probably end up being a side topic in relation to higher ed generally—subsumed under campus speakers, degradation of higher ed as a site for true intellectual freedom, curriculum limitations, tenure problems, etc. Hopefully your book will be out by then, so I can build on it, since I’ll want to talk capitalism and higher ed too. – TL

Thanks Tim.

My biggest problem with this stuff at the moment is the incessant piling up of “more of the same.” Tracing the connections between 1980s/1990s debates and the current round of ginned up outrage on/about college campuses is a little bit like cleaning out the stables while the horse is still crapping. While I’m trying to get to the bottom of it all, everything keeps piling up.

I hear you. This is the problem with recent/current history regarding culture wars, great books, canons, higher ed, cultural politics, capitalism, globalism, etc. But I also love those topics and talking that time frame. – TL

I’m happy the event went so well for you. As someone living in California I always wonder how these things go for folks in red states like Louisiana–or Texas for that matter.

I was also happy that you mentioned that policing partisanship is itself a form of political correctness, since it seems to me that there is so much political correctness in the self congratulatory narratives that the supposed foes of political correctness expect to hear from historians.

The need not to hear “bad” stories about the history of the US is in some ways the most belligerent form of political correctness.

Thanks Eran. Honestly, I think red state students may get a bad rap when it comes to openness to discussion, willingness to hear challenging views, etc. I was a little worried that they were expecting a more combative presentation than the one I gave and might be a tad disappointed, but they seemed to roll with it.

It occurs to me that I probably should have mentioned that I’m heading to the Hoover Institution this summer for a week-long research fellowship. I guess in this post, at least a little bit, I’m biting the hand that’s fixing to feed me — though I’m quite certain that neither Stanford nor the Hoover Institution will be affected in the slightest by my occasionally snarky historical commentary. They are getting along just fine, I’m sure. But I probably should have acknowledged that I’m going to be benefitting from the resources of the Hoover Institution, for which I am immensely grateful.

It always feels a little weird to come out swinging about something happening at Stanford — but that’s got to be one of the ancillary achievements of this project, I think: to not pull punches about an institution that is not just an object of historical inquiry for me but also an object of affection and a fondly-remembered place. That gravitational pull of the institution in my own history doubtless skews the history I’m writing, but that’s something to be aware of and correct for where possible. And it may skew the writing in interesting and potentially fruitful ways. We’ll see.

L.D., that’s an interesting and challenging position to be in, institutionally.

I bet many historians wrestle with such problems.

I am actually teaching now at the Stanford Online Highschool and had a good laugh with my students when I told them about Richard White and his clear attempt to trash Leland Stanford’s legacy in his book “Railroaded.”

I have always wondered how his position at Stanford inflected his research and his writing of that book. I bet he would have written a somewhat different book had he been at a different university.

But of course White could not have been more secure in his position at Stanford when he did so.

Eran Zelnick,

WRT the “need not to hear bad stories”. My kids graduated about seventeen years ago. The issue of “bad stories” is one of emphasis, as well as omitting good stories.

In fact, I recall that from half a century ago. Not that we had a need not to hear bad stories, but the kind of grinning triumph accompanying the “bad stories” as if to say, “you’ve been fooled by so called patriots and Joe McCarthy and we’re fixing you.”

My wife and I tutored some Nepali refugees a couple of years ago. A study sheet on WW II had fifty bullet points. Seven of them had to do with the war and forty-three with various issues of racial inequality.

So objecting to that sort of thing is not, I would suggest, a need not to hear bad stories about the US.

The apparent need is to peddle them. Yeah, we know Washington had slaves. He also was the first guy since Cincinnatus to overthrow a sitting government and then go home. Can we talk about both?

Thanks Richard,

I could say many things on this issue, but I think it ultimately boils down to very different ideas about what the task of the historian is.

To me there is little need for the historian to repeat what people hear day in and day out as part of our national indoctrination. There are cities, streets, money bills, schools, institutes, and more that are designed to glorify Washington. I for one would prefer in class to talk about some of the millions of other people that they have never heard about. For a truly democratic society to flourish we need to teach people how to question self-serving and gratifying narratives. The historian always makes an intervention, she does not make observations in a neutral environment.

Note for instance that I used the pronoun “she” instead of “he.” That too is an intervention designed to undermine our assumptions about who an historian is and how our language itself is not a neutral conveyer of facts.

I get that. My generation had WW II vets for fathers and uncles and we didn’t need “indocrtination”. We already knew. Now that those guys are gone, and we’re aging, some of the anti-atomic bombing arguments may go without contradiction, so there’s that.

However, the good stories are not necessarily part of what everybody knows. Everybody knows Washington was the first POTUS. Shouldn’t there be some talk about what it meant that there was a Society of The Cincinnati, as compared to all the other successful rebels? That, I submit, is not known and is not going to be known because, after she finishes up with the bad stories, the semester is over. And it would be silly to presume high school kids in 2015 know so much about WW II that only fourteen percent of the points on a worksheet need deal with it.

Well, it makes me feel better to know that a lot of parents make up the shortfall. “She said WHAT?” That’s what family dinner is for.

In theory, the academy is supposed to be the place for free inquiry, but in practice, the university, just like other employers often polices the speech of its employees. Academics, and its multibillion dollar sports cartel, the NCAA swiftly leapt into action to boycott the state of North Carolina for its reactionary bathroom laws, but as the Steven Salaita affair at my alma mater, the University of Illinois, has shown advocating for the Palestinian cause on twitter is grounds for dismissal. How many dozens of academics have been punished for stating opinions critical of Israeli policies or for advocating in favor of the BDS movement? How much support for draconian censorship comes from within the academy? How much support are senior faculty members willing to extend to cover the free speech of contingent faculty members?

I know who lost the campus culture wars, and I don’t think the Right won them.

I think in some parts of the US, the problem isn’t indoctrination with one kind of history, but being educated in any kind of history at all that exposes the student to major questions and issues. An American Studies student of mine who went to HS in Virginia is writing a paper on comparative history teaching between VA and TN. She was astonished when she moved here to discover how pathetic the history coverage is — in her words, it’s mostly Tennessee history and even then it leaves out some important bits. Even traditional ‘patriotic’ history courses are better than that, and at least give young people something to work with.

Some schools, and some teachers, and some syllabi, are pathetic. When I was in school, we went from Detroit, to Michigan, to US, to World twice, starting in grade three. Obviously, there wasn’t much world in our third grade class on the history of Detroit. Switching schools might mean a change on the pathetic continuum, or moving from Tennesee to World, which would also seem to be a major change. Now, Texas. Got a nephew in Austin. Texas has been very good to his family but they’re still virtue signaling about not being, you know, Texans. They did learn a lot of Texas history which, had he transferred to another state, might have seemed excessive. No harm done, as far as I can see. But, sure, there are differences.

Aaron Hanlon’s piece in The New Republic is an interesting read on no-platforming — or, as Hanlon calls it, de-platforming.

Why Colleges Have a Right to Reject Hateful Speakers Like Ann Coulter

Richard, I was just wondering the other day whether political discourse around the past election might have gone differently if the men and women who fought and won World War II were still in their prime. I recall a news story from a few years back about Buzz Aldrin, who is an American badass and has always been very fit for his age, punching some loudmouth in the face when that sorry fool was stupid enough to claim that the U.S. never landed on the moon. If there were more veterans of World War II still alive today and able to throw a haymaker, would we have so many clammy-skinned catfish-belly-white quasi-adolescents sporting “fashy” haircuts, strutting around spouting Nazi propaganda, and throwing stiff-armed salutes to compensate for their utter flaccidity of thought or character? Hard to say — but it’s an interesting thought experiment.

Oddly, though, the generation raised by World War II veterans went by a good ten to fifteen percentage points for a candidate openly supported by avowed fascists, neo-Nazis, and Klansmen. As Superman would say, “That’s un-American, boys and girls.” But I guess some people are never too old for a little youthful rebellion against the wisdom of their elders. Still, perhaps a more robust civic education when they were youngsters – something a little more thorough than the informal lessons that the never-gonna-be-the-greatest generation allegedly absorbed from fathers and uncles who had fought and won World War II – might have steered more of the babyboomers away from indifferently shrugging at fascism. Hard to say — but it’s an interesting thought experiment.

Or you could suggest that fit guys like me–did my post-grad work at Ft. Benning 1969–would have been so uncivilized as to smack around the commie supporters of the democratic candidates. After I got off active duty I spent the next fifteen years trying to keep in shape in case the Reds came over the IGB. So I get your thought experiment. For my sins, i was in a faith based peace-wonderfulness group for some years. After the USSR fell, the elephantine manuverings to have been on the side of the good guys after all were hilarious.

It’s juvenile and obviously dishonest to smear a candidate by his looniest supporters, but if you really want to, I suggest you consider it cuts both ways. Of course, that means considering USSR supporters were really bad guys. I do. You? Both ways. Just a thought exxperiment.

It’s not the USSR anymore, you know — just Russia now, though definitely run by ex-KGB. But yes, it is also horrible to think of the Russian influence on the current administration. And the avowed Nazis / white nationalists in the White House — Gorka, Bannon — may be the President’s looniest supporters, but they are certainly among his most powerful and influential.

All that chest-thumping and preening renders you a little too easily baited. But we already knew that.

L.D.,

Here is some background about the Buzz Aldrin incident. The “loudmouth” was moon landing hoaxer named Bart Sibrel, who lured Buzz Aldrin to a Beverly Hills hotel under false pretenses. Aldrin believed he was being interviewed by a Japanese television show. Aldrin attempted to leave the interview and was blocked by Sibrel who had someone film the encounter. Sibrel showed the tape to authorities in an attempt to get an assault charge against Aldrin. They determined that Aldrin was provoked, and no charges were filed. The incident is on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0VfAfzNEWOc

L.D. Russian influence….You know better. Point is, so does everybody else. You may have missed that memo. Try to keep up.

@L.D.,

A side note on Stanford.

You know a lot more about Stanford and its policies than I do. With that said, I glanced at the Inside Higher Ed piece, and it seems that Stanford’s policy prohibits institutional partisan speech. In other words, they don’t want speech that could reasonably be construed as Stanford as an institution taking a stand on partisan politics. That was the alleged rationale for the objection to the photo. I understand that in this case the rationale was v. weak, and also the complications re the Hoover Institution etc.

Nonetheless, if a Stanford professor writes, say, an op-ed saying “Trump is an authoritarian demagogue,” Stanford would have no grounds for objecting to this on the basis of its no-institutional-partisan-speech policy, because the fact that professor X teaches at Stanford cannot reasonably give rise to the inference that Stanford as an institution endorses whatever prof. X writes. And for Stanford to decree that no one who teaches there can express partisan viewpoints in an op-ed (or in the classroom, for that matter) would, istm, raise serious academic freedom issues and also possibly raise First Amendment concerns (despite Stanford’s not being a public university).

So while Stanford’s existing policy might have the effect of chilling some professorial speech (I don’t know whether it does, but it might), I’d think the univ. cannot have a formal policy prohibiting professors from expressing political views w/o opening itself up to lawsuits and possibly damaging faculty recruitment. Of course there are some schools, affiliated e.g. with fundamentalist or conservative denominations, that effectively put restrictions on faculty speech as a condition of employment, and the people who teach at those places accept that from the start. And if you teach in the theology school (or perhaps some other depts.) of The Catholic Univ. of America, you might be well-advised not to publish something attacking ‘authoritative’ Church doctrine on sexuality etc. if you want to keep your job. But for Stanford to have a similarly speech-restrictive policy I would think would be very bad for its image and reputation.

Louis, I get the purported rationale — though, as some of the articles covering this controversy point out, Stanford prohibited the prof from using the photo even without the university logo and even if she paid for the reproduction and distribution of copies. Again, there’s an institutional history behind hyper-sensitivity to “partisan” speech, a history that gives these sorts of controversies a different inflection there than they might have elsewhere, it seems to me. The outcry of the Faculty Senate in the late 1980s re: the Hoover director’s praise of Ronald Reagan, and how those fulsome remarks jeopardized the reputation of the school as a non-partisan institution is, I think, part of the iceberg beneath the surface here — as is the university’s loss of the Reagan Library. Stanford was the first choice of the Library foundation, but a multi-pronged protest effort from faculty and students cost the university that institution (or, some would say, saved the university from that institution). Most of the objections were not so much to the library as to the conservative think tank that was going to be attached to it, but the outcry over the Reagan library coalesced with the grousing about Hoover and the canon debates (and a few other controversies). It was a perfect storm, and reconstructing it in a historical narrative that makes for compelling reading for people who are not already invested in the inside baseball of the Farm is a bear of a problem.

Then again, I’m always loaded for bear.

Thanks, interesting. If I knew about the Reagan Library controversy there, I’d forgotten about it.

It might (?) be worth looking up, if you haven’t done so yet, the history of the JFK Library — not for direct parallels, but b/c I vaguely recall reading, so vaguely that I don’t entirely trust my recollection here, that originally the trustees (or whatever the right word is) originally wanted an institutional affiliation and eventually had to settle for a stand-alone site. But in that case the issues might have been, and probably were, less political than financial and logistical etc. Anyway, I’d have to look it up to be sure.

I, for one, am looking forward to your narrative about ‘the Farm’…

Hmm, repeated the word “originally”. I think once would have been enough. Sigh.