This week was a microcosm of modern African American history. When I wrote this, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) just opened its doors in Washington, D.C. A testament to years of hard work in getting the museum funded, the NMAAHC has already received considerable media coverage. It is also part of the Smithsonian’s system of museums–more than likely “the last great museum on the (National) Mall.” Intellectual historians will have plenty of time to consider the “civil religious” ramifications of a museum devoted exclusively to the Black experience (although it should not be limited to within the United States). But events to the south and west of Washington, D.C. put into stark relief the continuing irony of African American history.

Shootings of civilians by police officers caught on camera phone in Charlotte, North Carolina and Tulsa, Oklahoma have galvanized the Black Lives Matter and returned to the media forefront the eternal questions of race and citizenship in our nation. These are old questions—especially those related to police brutality. I have spent the week talking to others about police brutality. On Monday I was lucky enough to serve on a panel  discussion about police-community relations hosted by Benedict College, a Historically Black college in Columbia, South Carolina. There, everyone expressed frustration with police brutality, including police officers serving on the panel. None of us had heard about what happened in Charlotte until after the event was over.

discussion about police-community relations hosted by Benedict College, a Historically Black college in Columbia, South Carolina. There, everyone expressed frustration with police brutality, including police officers serving on the panel. None of us had heard about what happened in Charlotte until after the event was over.

I teach a course on the New South, and on Tuesday night found myself a little emotional talking about African Americans keeping alive the memory of emancipation during the rise of Jim Crow segregation. Borrowing from David Blight’s Race and Reunion (sections of which my students had to read for class Tuesday) I explained black resistance to Lost Cause mythology. Then I stopped, looked around the room, and said to my students: “My parents grew up during the end of Jim Crow segregation. They remember what it was like to use separate lunch counters and segregated schools. They never let me forget it.” I like to think my students, a bright and precocious bunch, understood my argument that the building of memory of the past is an ongoing process, especially relevant for today. I also like to think they did not notice the slight crack in my voice as I said that.

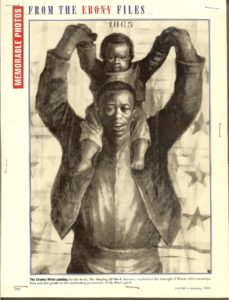

During times of modern crisis, I find myself looking to history to provide some loose guide to what can be done today. Perhaps I draw some strange comfort from the fact that my great grandparents dealt with some of the same issues in their day. “If they could make it,” I ruefully tell myself, “then, maybe, I can too.” And so it is with police brutality. I did a brief scan of some of my favorite archival sources—the Google Books archives of The Crisis magazine (the organ of the NAACP) and Ebony and Jet magazines. I found police brutality stories from 1936 in The Crisis (the earliest I have found, so far) and an eye-opening piece from Ebony on what to do if you’re black and pulled over by the police.

History cannot offer a salve for the pain of current events. But it does offer context. So in that sense, the timing is perfect for the opening of the NMAAHC. Reflecting on the endurance of African Americans in the face of slavery, segregation, housing discrimination, and yes police brutality, is especially needed now. To borrow from Howard

Brick’s book on the 1960s, we live in an age of racial contradictions. Since January 20, 2009, the United States—a nation built on slavery, time and again shown to be a hypocrite on matters of race and democracy—has been run by an African American man. Racism against a wide range of Americans has been a tragic hallmark of the Obama years. Not that it had disappeared after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But the racism of the last eight years offered a photo negative of the kind of America we hoped the 2008 election ushered in—a so-called “post-racial” era.

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote over a century ago, “How does it feel to be a problem?” His words, as always, remind us of just how old these problems are. I am asked, as an African American, to still think of myself as a “problem” by the rest of American society. The NMAAHC reminds everyone that African Americans are much more than that. But the crisis in Charlotte, the shooting in Tulsa, and the ugliness of modern politics reminds us that the “problems” of race and democracy will long be with us. History alone cannot fix them. But, perhaps, history can prod us to ask the right questions.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Very timely and moving post Robert. Thanks for writing and for teaching.

Seconding what L.D. said.

Thanks for the kind words everyone.

As I’ve said many times before, reading David Blight’s book literally changed my life. In the course of an education (which always necessarily lasts a lifetime, though some people manage to stop learning), sometimes a new way of thinking sort of gradually dawns on you. But sometimes it’s as if somebody has flipped a switch and flooded the whole room with light. That’s what reading and discussing Blight’s book was like. It flipped a switch and turned on the floodlights, illuminating the space between memory and history, showing that memory can cast a shadow, showing that memory has a history, and showing that history has a history too, all at the same time. It’s a stunning read, and especially essential for those of us who teach U.S. history in the south (though the Lost Cause has leached into curricula from one end of the country to the other).

So, so true. When I read this book I had much the same reaction. My students really found the sections I assigned, on Black memory and also the Lost Cause being born right after the war, of interest.

Thinking about writing a little blog post on David Blight talk at Sewanee symposium on 14 Amendment. As a cultural historian, I’ve been emphasizing how much the way we remember history–slavery, Reconstruction, “lost cause”–matters, but this 14th Amendment symposium was really useful for thinking about the legal aspect of the legacy of that era. Blight referred to 14th amendment as the “legal and constitutional DNA under which you live.” I can say I’ve never been so excited about the history of Reconstruction or legal history as I was after this symposium. (plus David Blight is a super nice guy and I was so glad he had dinner with several of my students)