Those of us who teach on a semester-based calendar will be putting the finishing touches on one syllabus or another over the next week. In my case, it’s five fabulous syllabi — five courses, three preps, on three different campuses, for two different employers. (I know: take a number.)

I’m not allowed to ban guns in my classrooms at the university campus, or in my office either, which I will be sharing with 11 other lecturers. I have thought about showing up to work every day with a pair of purple Nerf six-shooters in hip holsters, with a bandolier of orange foam bullets slung over my shoulder – yes, all of these items are real, and are in fact just lying around my house (we are terrible about Nerf safety) – but that’s probably against the rules.

I can, however, ban the use of cell phones and laptops. In the past, I have allowed the unobtrusive (i.e., not distracted nor distracting) use of laptops and cell phones, but have proscribed certain kinds of activities.

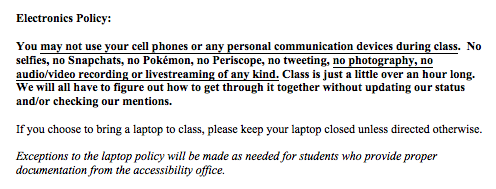

Here is the most recent iteration of my electronics policy:

The names of the apps are always changing, but the underlying principle of my electronics policy is the same: the classroom is a space where students (and even professors, to some extent) should feel free to ask questions and make mistakes and try out ideas without having their efforts broadcast in real time to the whole world (wide web).

In his fantastic interview with Frank Rich, published in November 2014, Chris Rock talked about (among other things) the challenge facing stand-up comedians in the age of cell phone videography:

It is scary, because the thing about comedians is that you’re the only ones who practice in front of a crowd. Prince doesn’t run a demo on the radio. But in stand-up, the demo gets out. There are a few guys good enough to write a perfect act and get onstage, but everybody else workshops it and workshops it, and it can get real messy….[I]f you think you don’t have room to make mistakes, it’s going to lead to safer, gooier stand-up. You can’t think the thoughts you want to think if you think you’re being watched.

The most obvious analogy here, of course, is the analogy between the stand-up comedian and the professor in a lecture hall, with the professor as the performer and the students as the audience.

But that’s not really how the classroom works. That’s not how my classroom works, anyhow. And, to be Goffman-esque about it, that’s not how any social situation works. We are all performative, and we are all learning as we go.

But in our society, some of us have never had the privilege of being in a social space where it is okay to make a mistake, while some of us have been able to get away with some pretty big mistakes on a regular basis without ever having to answer for them. Sociologist and public intellectual Tressie McMillan Cottom has described that inequality in terms of “who has the privilege of being an individual.” And as she subsequently explained, the “context collapse” of social media flattens out the dialogical landscape (essential, of course, for the most efficient extraction of surplus value from people’s intellectual labor) and renders all social situations, all contexts, equally subject to scrutiny (and monetization).

Much recent discussion about Twitter in academe has swirled around these intertwined issues. What is practice space v. what is public space, what is process v. what is product, what is an audition v. what is a performance? A graduate student giving a paper for the first time at an academic conference has a lot more at stake, and a lot more to lose, than a full professor – but both of them must now operate in a world where all academic space is becoming public in the broadest possible sense. The academy, like every other social organism in our age of gamified panoptical surveillance, is reeling from the effects of context collapse.

Well, I can’t do much to help the academy (though that never stops me from trying). But even as a lowly adjunct, I am allowed to establish (some) classroom policies and set expectations for how my students will interact with me and with each other during class.

My students will probably not like my electronics policy, and even after I explain my reasons for it – and I always do explain my reasons for course policies – they may not appreciate it. But I think they will benefit from it. I can’t proscribe everything that might have a chilling effect on classroom discussion this semester, but I can try to keep our world safe from Pikachu and Periscope and the panopticon for one golden hour.

They can tweet about the awful ordeal later.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

You know, this post really has me thinking about my own technology policy in the classroom. In the past, I’ve had no qualms about allowing folks to use laptops. With that said, I have gently recommended printing out readings for the class–because, as I argued in my syllabus, they’d get more out of reading them on paper due to having the option to write notes in the margins.

I have certainly come to enjoy modern technology, but I wonder how much my thinking and daily habits have been changed by use of Facebook and Twitter. I have even tried to cut back, desiring the privacy of thinking on my own. And I think your policy also helps our students adjust to “the real world” as well: when I worked in customer service, there was no way I could check my cell phone while working (unless done in a clandestine way).

Nicely done. Wise, too.

Just to play devil’s advocate: What about allowing the use of devices, but in focused ways—-by asking them historical questions relevant to your readings and discussions, and then teasing out better and worse answers? Or that could be a once per week, or once every two weeks phenomenon? You could create teams and see which could find the best answer in short order. So sure, it’s gaming. But games can be used to develop better historical thinking. …I propose this even though I’m not opposed, in principle, to outright bans.

I’m just reading this now as I saw the link from your June 30, 2017 post. First off, I agree with your points here. I have the same electronics policy, which I state on two occasions in my syllabus and announce verbally on the first day of class. In an ideal world I would not have to constantly remind my students about putting away their electronic devices before I begin, but alas, these are the times in which we live. In addition to the points you make, I would add that we live in a digital age of constant distraction (Trump is a manifestation of this). I want my students focused and have found after about ten years of teaching that while digital technology of course affords many benefits that no one would dispute, in the main I find that it both distracts and undermines many of the goals I want to accomplish in the classroom. Thankfully, my department chair supports my cell phone policy and there are other lecturers who share my views. I have been at other institutions where department chairs, clearly taking orders from above and prioritizing only the for-profit, bottom-line of universities and the student-as-customer mentality, are willing to second-guess pedagogical approaches I have worked hard to think about and develop. And finally, although it is not the main point of your post here, I gasped when I saw your opener about five syllabi and sharing office space with so many other lecturers. No one with your accomplishments–especially a book–should have to endure these conditions. It’s almost like we’re hamsters on a wheel…

Steve, thanks for the kind words. I probably should have run some form of that post here, but really didn’t want to leave anyone with the impression that it’s in any way an official position of USIH.

But for those who are wondering, here’s a link:

Quick Thoughts on the OAH “Amplified Initiative”

As to my load last fall, that was actually pretty light as adjuncts go. I have a friend who has regularly taught 10-14 sections a semester — face-to-face at two or three different college/university systems, and online as well — to make ends meet.

More on all this later/elsewhere.