As I get ready for another fall semester at the University of South Carolina—finishing a dissertation and teaching a course on “the New South” of late 19th century and 20th

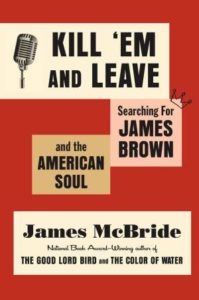

century America—I decided to finally complete a book I have longed to read on my coffee table. James McBride’s Kill ‘Em and Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul was released to considerable fanfare earlier this year. About the life and legacy of the musical legend, McBride’s book is a meditation on African American life during and after the age of segregation and Jim Crow (which, by the way, is a reminder that Tim Lacy’s series on Jesse Jackson is another reflection on that history). But beyond that, Kill ‘Em and Leave should leave any reader—certainly any historian—thinking about the places within America left behind by modern American history.

McBride, to his credit, does not set out to write a biography of James Brown. There are enough of those as it is, and McBride himself admitted in the book that he was not the best person for a new book on Brown. Yet McBride’s reporting and writing points to not just the mystery of who the real James Brown was—it’s something that can never be figured out, because as McBride pointed out in the book, no one knew who the real Brown was while he was alive—but also considers the relationship between Brown and the regions of  Georgia and South Carolina that shaped him the most.

Georgia and South Carolina that shaped him the most.

Before continuing, I have a confession to make. As a native of Augusta, Georgia, a city often considered Brown’s hometown, I had a keen interest in reading McBride’s book. I still recall the national attention the city received for Brown’s memorial service on December 30, 2006. Watching the memorial service on the local news (there was no way I would even try to go to the service), I was struck by a deep sadness. For all his flaws, for the fact that Brown was often the butt of national jokes in the 1990s and 2000s, Brown meant

something to African Americans in Augusta, Georgia and just across the Savannah River in South Carolina. He donated turkeys every year for Thanksgiving to locals. He often led toy drives during Christmas season (which still continue in his name). Augusta is really only known to outsiders for two things: the Masters golf tournament and James Brown. As McBride makes clear in his well-written book, while the Masters is a façade—an attempt to make Augusta look far better than it probably deserves—James Brown and his life story represents both what Augusta was and what, since the end of the Civil Rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, it has become.

McBride’s book makes a case for studying cities like Augusta in the context of American, Southern, and African American history since 1965. Smaller cities like Augusta have been especially hit hard by racial strife, white flight, deindustrialization, and the movement of other low-skill jobs from the American South to Mexico and elsewhere. As historians, cities like Augusta—or for that matter, Columbia and Greenville, South Carolina, among others—can provide new case studies to understand what happened in the South since the “end” of the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1960s. That history very much intersected with the life of James Brown. A symbol of the best of the rural and small city South, Brown thought of himself as an African American and a Southerner. He competed with African American singers and performers from Northern cities and labels after surviving fellow Southern performers in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

makes a case for studying cities like Augusta in the context of American, Southern, and African American history since 1965. Smaller cities like Augusta have been especially hit hard by racial strife, white flight, deindustrialization, and the movement of other low-skill jobs from the American South to Mexico and elsewhere. As historians, cities like Augusta—or for that matter, Columbia and Greenville, South Carolina, among others—can provide new case studies to understand what happened in the South since the “end” of the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1960s. That history very much intersected with the life of James Brown. A symbol of the best of the rural and small city South, Brown thought of himself as an African American and a Southerner. He competed with African American singers and performers from Northern cities and labels after surviving fellow Southern performers in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

James McBride deserves credit for delving into the life of James Brown from fresh angles. He approaches a curious sphinx of a public figure with a broad brush. It is the only way, thinking about James Brown, that such a man can be approached by a writer. But for  historians, it should spark fresh discussions about the Black South after Martin Luther King, Jr. It is a “post-Soul” South I have written about before. But Brown kept what was left of that soul alive, as long as he was with us. And despite his run-ins with the law, money problems, harsh relations with women, Brown remains something of a hero in the Deep South. The “American Soul” that Brown represented was unabashedly black and southern, and also unmistakably complicated. The man who sang “I’m Black and I’m Proud” was later criticized for meeting with, and supporting, President Richard Nixon. He was internationally known, yet James Brown always felt underappreciated by the citizens of Augusta. Brown often preached self-help—and was particularly close to two other controversial (yet also never-to-be forgotten) African American notables, Al Sharpton and Michael Jackson.

historians, it should spark fresh discussions about the Black South after Martin Luther King, Jr. It is a “post-Soul” South I have written about before. But Brown kept what was left of that soul alive, as long as he was with us. And despite his run-ins with the law, money problems, harsh relations with women, Brown remains something of a hero in the Deep South. The “American Soul” that Brown represented was unabashedly black and southern, and also unmistakably complicated. The man who sang “I’m Black and I’m Proud” was later criticized for meeting with, and supporting, President Richard Nixon. He was internationally known, yet James Brown always felt underappreciated by the citizens of Augusta. Brown often preached self-help—and was particularly close to two other controversial (yet also never-to-be forgotten) African American notables, Al Sharpton and Michael Jackson.

As I reflect on the one-year anniversary of the death of another son of the South, Julian Bond, I realize both these men witnessed incredible changes in the land of their birth and upbringing. But it is also clear to me that this story, like so many others, is still incomplete. As a historian it is fine to admit this. After all, if every historical narrative was at risk of being told and quickly accepted as “truth,” our field would be in dire straits. So, in reflecting upon people like Brown and the world he came from, I am comforted by knowing that there is still so much to be said about recent American history—just as there are so many forgotten, under-told, and unknown stories from history.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I like his retort to clueless and dishonest hidebound voices of that time (and this one), “I don’t want nobody to give me nothin’; open up the door, I’ll get it myself.” Music, and James Brown’s music in particular, has a more important role in creating community than people seem to give it credit for. I’ll be looking forward to your further thoughts on Mr. JB, especially if you focus on the music.

Thanks for the comment. You’re exactly right–he played a major role in creating community. I’ll definitely be saying more about James Brown soon.

and he saved boston as the documentary showed and he also showed up the stones something terrible on the TAMI show.