With it being Black History Month, I find myself thinking about works written by African American men and women that have influenced me the most during my career as a student of history. There are many to choose from, and I hope you, the reader, will chime in with your own favorite works of intellectual history written by African Americans. I would argue that the subfield of African American intellectual history has its roots in the slave narratives written by Olaudah Equiano, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Jacobs, among others; the poetry of a Phillis Wheatley and the plays of William Wells Brown; and the histories written by George Washington Williams. In all of these works, African Americans defended their humanity to skeptical white audiences by proving their intellect to be the equal of anyone else. Since then, African American intellectual history has continued to push the contours of whose voices deserve attention from intellectual historians and intellectuals in general, as the United States continues to wrestle with the multifaceted question of “race relations.” Interest in the field has never been higher, evidenced by the existence of the African American Intellectual History Society (and their upcoming conference), and strenuous debate about the writings of individuals such as Ta-Nehisi Coates.

The following list is, of course, not meant to be comprehensive. And by all means, add yours in the comments below:

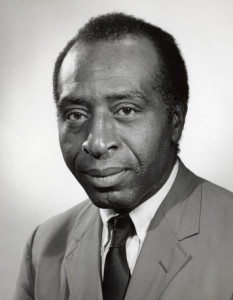

The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967)—Harold Cruse’s polemic on African American intellec tuals during the Cold War era leaves a bit to be desired. He barely talks about intellectuals from beyond Harlem. Cruse’s personal grudges get in the way of critique and analysis that, at times, needs a healthy dose of nuance to be interesting to readers unfamiliar with American Left rivalries from the 1950s and 1960s. Yet, I could not put this list together without mentioning Cruse’s magnum opus.

tuals during the Cold War era leaves a bit to be desired. He barely talks about intellectuals from beyond Harlem. Cruse’s personal grudges get in the way of critique and analysis that, at times, needs a healthy dose of nuance to be interesting to readers unfamiliar with American Left rivalries from the 1950s and 1960s. Yet, I could not put this list together without mentioning Cruse’s magnum opus.

Jim Crow Wisdom (2013)—Jonathan Holloway’s reflection on African American memory, cultural identity, and intellectual debate after 1941 is a fascinating mix of memoir and narrative history. Jim Crow Wisdom is, admittedly, the kind of book I would like to write someday. By examining the relatively untapped and rich history of African Americans remembering the past through their shared experiences, Holloway brings to the surface areas of American memory and intellectual history that would otherwise have been forgotten in the memory hole of recent history.

Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women (2015)—The editors of this book—Mia Bay, Farah J. Griffin, Martha Jones, and Barbara Savage—deserve considerable credit for assembling a collection on a mostly ignored subfield of intellectual history: Black women’s intellectual history. I can think of numerous figures who would make excellent subjects for any intellectual historian: Anna Julia Cooper, Coretta Scott King, bell hooks, Angela Davis, Ida B. Wells-Barnett. However, what makes Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women

so important is that the authors point to numerous topics for intellectual historians to tackle and say, in essence, “The material and interest is there. Join us!”

The Challenge of Blackness (1970/2011)— I have here two books with the same title. The 1970 iteration, a collection of essays by Lerone Bennett, capture the intellectual, cultural, and political ferment in America during the early 1970s. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s declaration of “Where do we go from here?” rang with increased urgency in Bennett’s essays. Would it be liberation, separation, or integration, as a special issue of Ebony asked in 1970? Or something else entirely? Even Bennett wasn’t entirely sure. But his work, and the work of other public intellectuals such as Vincent Harding, shaped black intellectual thought for decades to come. That story was captured by Derrick White in his book on the Institute of the Black World. Reminding us that, for many black intellectuals, the choice between black power and civil rights integration was too simplistic and not satisfying at all, White’s study of this Atlanta-based think tank is an illuminating study of the 1970s.

The Souls of Black Folk (1903)/Black Reconstruction (1935)— Both these works by W.E.B. Du Bois show where his mind was during two different moments in the first half of the twentieth century. Souls represents Du Bois still hoping to change opinion on the “Negro Question” of the age. By 1935, Du Bois’ turn to the Left meant that he saw the Reconstruction era as a moment of lost promise for white and black Southerners. These two books have shaped me the most as a scholar and thinker. Black Reconstruction’s chapter “The Propaganda of History,” when I read it as an undergrad at Georgia Southern ten years ago, pushed me to take the plunge into a career as a historian. But both books also opened up my interest in black intellectual history. Without them, it is not an exaggeration to say you would not be reading a blog post from me right now.

Enough about me—what are some of your favorites? Is it C.L.R. James The Black Jacobins? Daryl Scott’s Contempt and Pity? Lawrence P. Jackson’s The Indignant Generation? I look forward to seeing more entries.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this excellent list, Robert. I’m currently reading & enjoying theologian Howard Thurman’s autobiography, “With Head and Heart,” with an eye toward tackling next the documentary editions of his writings and sermons (more: http://www.bu.edu/htpp/). Pauli Murray’s “Proud Shoes” also helped me think about family history and American identity.

Thanks for both these recommendations! Thurman and Murray are both fascinating figures in their own right–and Murray, especially, seems to occupy an underrated role in American history. Not only was she involved with the Civil Rights Movement, she also co-founded the National Organization for Women.

I learn something new — and admire it even more — during my annual re-read of Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom

That’s a classic. Thanks for mentioning–one of the best on capturing intellectual history from the bottom up, i.e. from activists on the ground.

One of my favorite recent works, although not by an historian, is Anthony Pinn, The End of God-Talk, where he maps out the major themes in black humanist theology. I also really love Erik McDuffie, Sojourning for Freedom, an amazing look at the ideas of black female Communists before the Civil Rights Movement.

And thanks for the shoutout for the AAIHS conference. I hope you can make the trip up to Chapel Hill.

I’ll have to check those out! Black humanist belief is something that’s started to interest me more, especially after reading your work.

And I’m looking forward to the AAIHS conference–I’ll be there!

Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider and Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark were absolutely earth-shattering for me when I first read them in college.

And I haven’t read it since, but Cornel West’s American Evasion of Philosophy was probably the first work that I read as intellectual history, as a narrative about a tradition and pattern of thought across time. But it is important and worthwhile for far more than those biographical reasons!

Thanks for mentioning these Andy. All *crucial* works fro American intellectual history. And West’s book, in particular, is important, because it often seems overshadowed by his later work.