Anyone who attended the plenary this weekend on Russell Jacoby’s The Last Intellectuals, which was just one part of a vigorous and immensely pleasurable conference, knows that Leo Ribuffo in particular, but Claire Potter and Jonathan Holloway as well, were unsparing in their critiques of that book’s narrow vision of who an intellectual can be. Drawing from their own life experiences, Potter and Holloway demonstrated the intellectual vitality of communities for which Jacoby’s argument simply had no time and no apparent inclination to see in 1987. Ribuffo’s critique was in some ways more direct: Jacoby’s definition of “intellectual” was merely “honorific” (I imagine, since Ribuffo brought him up, that he meant that in the Veblenian sense: the word dots The Theory of the Leisure Class as a sort of leitmotiv of disdain and irony).

Yet Potter and Holloway and even Ribuffo’s frontal attack leave, in an odd way, the central contention (as I understand it) of The Last Intellectuals untouched. What each critique does is encourage us to look away from the center of the world Jacoby described and to acknowledge how much lies around that center, to find in the margins what Jacoby stipulates became impossible at the core. But what their critiques do not do, I feel, is challenge Jacoby’s argument that, within the same demographic category (white, urban, well-educated men), there was a distinctly visible decline in deliberate engagement with a broad readership. Considering The Last Intellectuals not as a social diagnosis but as an account of a failure of cohort replacement, I imagine that many intellectuals (in the non-honorific but rather sociological sense) today would still basically assent to Jacoby’s narrative. The university may have been the starting point for a “long march through the institutions of power” for women, sexual minorities, and persons of color, but it was, the consensus might reluctantly admit, the long, plump sofa on which the men who were to succeed the New York Intellectuals schluffed and schlumped. The message that so many have taken away from Jacoby’s work is that, well, not everyone can be Edmund Wilson or Irving Howe, but someone in the 1980s (or 1990s or 2000s or 2010s) should have been

.

Of course, there have been other critiques which point out how dependent even Jacoby’s icons were on university paychecks. Jacoby certainly understated the degree to which, even if they were not securing tenure-track appointments, the generation he lionized often picked up short-term university teaching to cover their bills. (The new biography of Saul Bellow provides abundant evidence of the prevalence of this pattern.) Yet the sociology behind The Last Intellectuals has never been the point for most people, although as Potter argued, it is probably at its best in its arguments about space. Instead, the book has been and continues to be read, I think, as literary criticism, as a diagnosis of a generational change in prose style; all other considerations–in what venues that prose appeared, whom it addressed, who or what paid for it, where it was written–are secondary. That is, my innermost materialist tells me, pretty silly.

There remains too often an unexamined assumption that style and accessibility go hand in hand. Anyone who has ever looked over a socialist pamphlet or the Catholic catechism will recognize this as a fallacy: the presence of “jargon” does not preclude wide readership, though one might object to these cases as ones where compulsion buffers the the more abstruse points of Christology or Marxism. Even still, there are many reasons why even “average, intelligent readers” (the hypothetical subject of the middlebrow) do tackle difficult texts; we can merely look to the current state of television for evidence that complexity is not in and of itself a deterrent.

Instead, what I imagine may have convinced Russell Jacoby’s readers in 1987 and still today that his diagnosis was correct is in reality a very simple fact, a very pedestrian observation. Great works of the mind once appeared in editions clearly meant to be widely read and continued to appear in those formats long enough to indicate that people actually were reading them widely. Now, they do not.

I have on my desk at this moment a mass-market paperback edition of H. Stuart Hughes’s Consciousness and Society: The Reorientation of European Social Thought, 1890-1930. From my desk I can see a row of mass-market paperbacks of a similar sort: Christopher Lasch’s The New Radicalism in America (1965); Eric Goldman’s Rendezvous with Destiny (1952); Digby Baltzell’s The Protestant Establishment (1964); Will Herberg’s Protestant Catholic Jew (1955); David Montgomery’s Beyond Equality (1967); Stanley Edgar Hyman’s The Armed Vision (1955); Erik Erikson’s Young Man Luther (1962); C. Wright Mill’s The Marxists (1962); John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Affluent Society

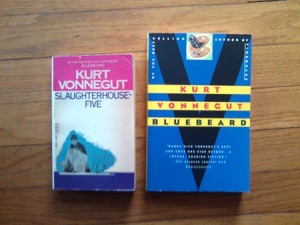

(1958); a clutch of Richard Hofstadter’s work; and, well, you get the point. It is difficult to imagine works published not even that much later as mass-market paperbacks–the kind on the left in this image, rather than the trade paperback on the right.  If anyone knows of a mass-market paperback version of Jackson Lears’s No Place of Grace, for instance, or Alan Brinkley’s Voices of Protest (1981 and 1983, respectively), please let me know. But we must all be familiar with this massive shift, albeit subliminally: there are probably few of us who do not own a mass-market copy of some mid-century scholarly study.

If anyone knows of a mass-market paperback version of Jackson Lears’s No Place of Grace, for instance, or Alan Brinkley’s Voices of Protest (1981 and 1983, respectively), please let me know. But we must all be familiar with this massive shift, albeit subliminally: there are probably few of us who do not own a mass-market copy of some mid-century scholarly study.

If there was, as I suspect, a sort of collapse in publishing books like Rendezvous with Destiny in mass-market form, a lot more needs to be explained than has been explained, and I don’t find the hypothesis that Eric Goldman wrote significantly differently than Alan Brinkley, or that Stuart Hughes’s prose is easier to read than Jackson Lears’s very convincing. Besides, in the back of my copy of Consciousness and Society

is a list of other books offered by Vintage Books, the paperback division of Random House. Presumably, the following books would also have been available as mass-market paperbacks:

- Robert Lekachman, The Age of Keynes

- Rodger Hurley, Poverty and Mental Retardation: A Causal Relationship

- Alfred Lindesmith, The Addict and the Law

- Robert Presthus, The Organizational Society

- Lionel Tiger (awesome name), Men in Groups

- F. S. Perls, Ego, Hunger and Aggression: Beginning of Gestalt Therapy

There are other, better-known titles as well in the list, but I singled these out because I have never heard of any of them and I’m guessing that few of you are familiar with any of these works either; they are not, it is safe to say, the work of “public intellectuals.” More impressive still is the full list, for even if I have heard of many of the other titles, it is very difficult to imagine any of them selling enough copies to merit reprinting as paperbacks. Otto Rank’s The Myth of the Birth of the Hero? How many copies did that sell? Even if a few sold decently, was it enough to make up the cost of those which did not?

The same question goes for those paperbacks on my shelf: did they actually sell well enough to justify the additional effort of reprinting? Of course, that is question we can answer empirically, and I have no evidence either way. And it is entirely possible that we don’t see any academic histories reprinted in mass-market editions because trade paperbacks are far cheaper to produce (and can still be sold for more than mass-market paperbacks). Note, for instance, that Erik Larson’s books, popular as they are, appear only in hardcover and trade paperback.

But the larger point is that we are not asking questions like these, and that without answers to them our attempts to attribute some monumental shift in the intellectual culture to style and ambition (or their lack) are essentially idle, a moralizing pastime rather than a serious effort to understand. Before we can have a real conversation about what kinds of history we must write to reach a broad audience, to generate public engagement, perhaps it would be better to be sure that those academic historians or other intellectuals whom we take to be models of public engagement really did reach the audience we imagine, and that they did so on their own merit, on the force of their writing, their moral urgency, and their eagerness to be read.

Instead we must take much more seriously the likelihood that other factors (the economic vagaries of publishing, the presence of philanthropic subventions which subsidized the cost of reprinting academic books, or some other influence) also had something to do with why we can still read battered old copies of C. Wright Mills and Will Herberg in hand-sized editions, as well as the works of scholars whom no one would call a public intellectual. It is in the explanation of the existence of those paperbacks published by non-public intellectuals that we may find our answers for why there was never a second Richard Hofstadter, why from a certain vantage point, Jacoby could see that generation as the last intellectuals.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I heartily agree, on every point. The consolidation of the publishing industry and the bookselling trade resulted in a collapse of physical space — space in catalogs, space on store shelves — for non-academic nonfiction aimed at that general educated reader. (I wrote about that some here: The Procrustean Publishing Market.) The market has had a narrowing, flattening effect on book publishing. Someone can argue that “the internet” has created a habitat in which a vast diversity of authors can reach an equally vast and diverse audience — but the market has had a flattening effect here too. Yes, writers can call out to publics — or call publics into being — and so work as public intellectuals. But the pay generally isn’t great (the pay generally isn’t there at all) and it’s not possible for most writers to make a living at it. So while the adjunctification of the academy is shutting down that stultifying sinecure that Jacoby warned against, and possibly driving “intellectuals” back out into engagement with “the public,” that move of writers to the virtual space of the internet hasn’t been accompanied by a move of salaries/compensation. It’s not the “content providers” making money off of the internet, but the companies who aggregate, index, data mine, and monetize that content.

Excellent points, L.D., and to his credit, I think Jacoby even recognizes how ghastly the shrinkage in remuneration for things like book reviews has been. (At least I remember him saying something about it in D.C.) Anecdotally, a number of my friends who have left academia are now writing or have written for some of these content aggregators in a more permanent, non-freelance role. And as we’ve seen with Gawker Media and a few other outlets, there is a move toward unionization among these writers, which could have quite profound effects on the way any of the Salon/Buzzfeed/Huffington empires run (and more importantly, on how they pay their “content providers”).

An indispensable work on the “paperback generation” that speaks in part to several questions and topics raised here is Loren Glass’s Counterculture Colophon: Grove Press, the Evergreen Review, and the Incorporation of the Avant-Garde (Stanford University Press, 2013). Here’s one snippet:

“On the one hand, individual ownership was one component of this [i.e., the boomers’] generation’s relationship to print, and in some ways a misleading one, since paperbacks were frequently shared as a form of collective property. On the other hand, assigned reading lists were only one delivery system whereby these books got into the hands of college students, whose loyalty to Grove Press nurtured a whole common culture of revolutionary reading in the 1960s. [….] [P]rivate reading and public life were powerfully stitched together in the 1960s; to be in the Movement meant, at least partly, to be reading certain books, and many, if not most, of those books were published by Grove Press.”

And another: “…[I]n the second half of the 1960s, Grove expanded and enhanced both the investigative reporting and radical rhetoric of the Evergreen Review, publishing double agent Ken Philby’s revelations about British and American intelligence; Ho Chi Minh’s prison poems; extensive reports on urban riots and ghetto activism; eyewitness accounts of the events of May 1968, the Democratic Convention in Chicago, and the trial of the ‘Chicago 8’; interviews with My Lai veterans and other exposés on the Vietnam War; and numerous articles by and about the New Left, Weather Underground, Black Panthers, and other revolutionary movements throughout the world. In these efforts, Grove sought to merge literary and political understandings of the term ‘avant-garde’ in the belief that reading radical literature could instill both the practical knowledge and psychological transformation necessary to precipitate a revolution.”

Thanks, Patrick! It sounds like I really need to read that book!

I second LD on her comments about the contraction of the publishing industry and the subsequent shrinking of the remunerative space for public intellectuals. I also cannot help but think the transformation and fragmentation of the “public” is central our ongoing fascination with Jacoby’s declensionist narrative. Hearing about those paperbacks makes me ask: who read them? How many of those who bought a C. Wright Mills mass market paperback ever read it? I wonder how much of the market for public intellectuals was one of prestige transference, whereby having it on your person or in your personal library would signal to others that you were a certain type of sophisticated reader or thinker. You still see that in fiction to a certain extent (lugging around “Infinite Jest” seems to be an example of this, at least in Boston) and, even more so, in prestige TV. Nonfiction lacks the nuance of these other mediums because simply reading nonfiction, no matter its origins, already paints you into a certain elite readership distinct from the young adult reading masses and the Man-Booker-Prize-reading fiction snobs.

I just do not think being well-read means the same thing that it did 25 or 30 years ago. There are still a few topics where a historian can still make a sophisticated argument and find a wide readership (Timothy Snyder’s work on World War II and the Holocaust seems to have done this). Still, I think the decline of the public intellectual says much more about the changing public than about the changing intellectual. I think we would be mistaken as a professional class if we thought re-capturing a lost public was a solution to the crises in the humanities and social sciences. Rescuing these fields requires a reassertion of the value of our work to universities in the thrall of STEM instrumentality, a process less about public engagement and more about communicating with our peers in other disciplines.

Andy,

I haven’t read the comments properly yet but I have read your post.

I hope you won’t take this the wrong way, because I have very great respect for your erudition and wide range of reference, but simply because you have not heard of an author does not necessarily mean the author is obscure.

On that list you provide, I’m familiar in a general way with Robert Leckachman and Lionel Tiger. Lekachman (no longer alive) was indisputably a public intellectual in the ‘sociological’ sense; he wrote fairly prolifically for a range of publications from The New York Times Book Review at one end of the circulation spectrum to Dissent at the other. Lionel Tiger (who might or might not still be alive, sorry I don’t have time to check) is perhaps somewhat more difficult to classify, since I don’t think he published a a huge amt in the kind of outlets Leckachman did. But Tiger’s popular books on anthropology sold well, I’m fairly sure, and are frequently cited. The book of his you list, Men in Groups, is an anthropological take on ‘male bonding’, written for a wide audience, and not an obscure title by any stretch. How this affects your basic argument in the post, I don’t know.

p.s. Leckachman was the sort of public-intellectual economist who helped convey left-liberal economics to a wide non-specialist audience; probably just a notch or two in terms of readership below, say, J.K. Galbraith or Robert Heilbroner.

Andy,

This is a fascinating line of inquiry and I couldn’t agree with your argument more–Jacoby’s thesis demands more sociological research. It has almost nothing to do (as Robin pointed out) with public style. Was Trilling a particularly “readable” writer? Was Sontag? Was Lasch? I suspect all three were far more difficult in tone and pacing and syntax than your average Partisan Review / NYRB public intellectual, and yet they are held up as paragons of the PI species.

Does anyone seriously doubt that, given the chance to go “public,” the folks who write these days for the LA Review of Books, Avidly, Public Culture, or indeed, this blog would shrug off the mantle of intellectual and devote themselves to specialized academic research? No, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Let me just add two more links to the pile accumulating. Back in January, Louis Menand wrote in the NY’er about the paperback revolution and the difference this made to middle-class taste: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/01/05/pulps-big-moment

_ALH_ editor Gordon Hutner has a study called _What American Read_ covering the years 1920-1960 that focuses some on marketing of middle-class books.

http://www.amazon.com/What-America-Read-Taste-1920-1960/dp/0807832278/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1445389283&sr=8-1&keywords=gordon+hutner

Funny, b/c that anecdote at the beginning of Greif’s book about discovering the discourse of man in his parent’s basement turns out to fit your thesis as well–the discourse of man by way of Fromm, Arendt, etc. was delivered via old paperbacks.

I’m looking over at my tiny little 1950s copies of _To the Finland Station_ and _The Liberal Imagination_ as I write this . . . .

Oh, and the brutal empiricist in me would like to know: how does one go about researching sales figures for paperback publications? Through Publisher’s Weekly or by going directly to a particular publisher’s historical records?

In a recent re-issue of _The Liberal Imagination_, Menand noted that Trilling’s book sold 70,000 copies in hardcover and a whopping 100,000 copies in paperback in 1950. Where did he get those #s from? How could we find out the same for, say, Hofstadter, Kazin, Howe, etc.?

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/09/29/regrets-only-2

Great piece. Cf. Corey Robin’s remarks at the same convention.

Yikes! I was going to reply to each comment, but I don’t want to swamp the “Recent Comments” section on the right toolbar, so I’ll just reply in a batch.

Matt,

Very good points. I suppose I am simply interested–even apart from the larger stakes of the argument about “how the humanities can be saved”–in whether Jacoby is *right.* Even a little bit. I don’t think he is, but I feel that we have not asked the right questions to validate or invalidate his basic narrative about the non-replacement of a cohort of publicly-engaged, white, metropolitan-based male scholars and critics. Were the NY Intellectuals really not replaced, or have we been looking at them wrong (and giving them too much credit)?

Louis,

No offense taken at all–I’m thrilled to have more information about these two figures. I mean, in a larger sense, this is my point: we need to know more about this world that we think we’ve lost, and until we do, we’re just shooting in the dark. My sense is that, generally speaking, there *were* many books published as mass-market paperbacks that were not written by people who would have been recognized as public intellectuals at the time. But perhaps that’s wrong! What we need is research into the broader ecosystem of these paperbacks–why were so many published, how did publishers choose which books to reprint, and did they actually sell? If so, who bought them? And if not, why did publishers stick to this business model of reprinting what appears to be a fairly large number of academic-oriented studies on a fairly wide range of topics? Those are questions we can’t answer with Jacoby.

Patrick,

Absolutely. I should have flagged work that has been done (Menand’s piece is in part on Paula Rabinowitz’s book) and, as the other Patrick pointed out above, the Loren Glass book has much to say about these questions. I hope (for all our sakes) that we’ll have better answers on some of these questions soon–both the empirical ones about sales figures and more interpretive/synthetic ones as well.

FWIW, I think some of this credit should also go to Franco Moretti; while many of his techniques are held at arm’s length in History and English, I think the orientation toward refusing to generalize about “Literature” based on our knowledge of the canon alone has taken root. Of course, that wasn’t Moretti alone–Margaret Cohen has been important, and research on the middlebrow like Hutner’s–but I think Moretti has pushed it the most effectively.

Jim,

Thanks! I wanted to leave the connections to Robin’s talk open (I’m hoping others will be reflecting on his keynote here), but I was absolutely thinking about it as I wrote.

A couple belated comments:

1 I still miss the WPost’s BookWorld, just one of the now gone newspaper book reviews.

2 on the brighter side, I don’t remember in the 1960’s a lot of authors on book tours. And there certainly wasn’t a Book TV channel. From wikipedia: “Book TV covers established and upcoming nonfiction authors, mainly in the subject areas of history, biography and public affairs. Approximately 2,000 authors are featured annually,[3] and in one year may cover as many as 60,000 titles.[4]”