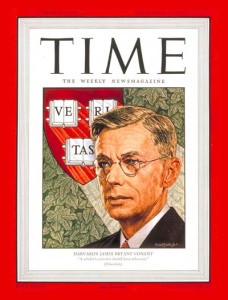

In 1945, a Harvard committee issued the extraordinarily influential report General Education in a Free Society, also known as the Red Book (or, often, the Redbook, which shouldn’t be confused with the women’s magazine, though that would be amusing). Issued under the leadership of, and with an introduction from, Harvard President James Bryant Conant, the report has received a great deal of attention from intellectual historians and from historians of education, so I will not repeat their labors here. What I do want to do is look at an earlier Conant project that I stumbled onto in the long digital corridors of HathiTrust.

In 1945, a Harvard committee issued the extraordinarily influential report General Education in a Free Society, also known as the Red Book (or, often, the Redbook, which shouldn’t be confused with the women’s magazine, though that would be amusing). Issued under the leadership of, and with an introduction from, Harvard President James Bryant Conant, the report has received a great deal of attention from intellectual historians and from historians of education, so I will not repeat their labors here. What I do want to do is look at an earlier Conant project that I stumbled onto in the long digital corridors of HathiTrust.

What I found are two reading lists in American history and literature from the Committee on Extra-Curricular Reading published for 1937 and 1938. The only reference I have found to this project in recent scholarship is a passing one in Wendy Wall’s (excellent) Inventing the American Way: The Politics of Consensus from the New Deal to the Civil Rights Movement. Debuting concurrently with the new doctoral program in the “History of American Civilization,” the Harvard lists were tied to exams that could be taken for monetary prizes to be bestowed upon, as The Crimson put it, “the top men.” (The prize was $100, or about $1650 in today’s dollars—not bad! The Crimson also noted tartly that “those who are not fortunate enough to receive the prizes will be given certificates merely for passing the examinations.” Guided by Howard Mumford Jones, F. O. Matthiessen, Frederick Merk, Arthur Schlesinger, Sr., and Samuel Eliot Morison (among others), the lists and examinations were also supplemented with public lectures; two sets of these sponsored lectures that I found in a brief scan of The Crimson were given by Felix Frankfurter, speaking to the topic, “The Court and Mr. Justice Holmes,”[1] and by Bernard De Voto, on “The American Historical Novel.”

The reading lists were aimed especially at undergraduates who were not pursuing courses in U.S. history, although copies of the reading list were also available to the public free of charge. My colleague Tim will be especially interested to note that Conant stated that he hoped the lists would “prove that an individual may continue his education throughout life by disciplined reading on an informal basis… It is an attempt to counteract the idea that the only road to knowledge lies through formal instruction in regular college courses.” Conant said elsewhere, “A true appreciation of this country’s past might be the common denominator among educated men which would enable them to face the future united and unafraid.” As Harvard historian Crane Brinton wrote in The American Scholar, “Nothing less than the genuine command of a whole culture is aimed at.”

The 1937 list included some 290 books, but the exam covered only 24, asking students to write essays on themes to be found in books such as the Beards’ Rise of American Civilization, Henry Adams’s Education, Francis Parkman’s Pioneers of France in the New World, Lewis Mumford’s The Golden Day, and Carl Sandburg’s biography of Lincoln, as well as Walden, Franklin’s Autobiography, Leaves of Grass, and the novels Moby-Dick, The House of the Seven Gables, and Henry James’s The American.

I am not quite sure what happened to these examinations; Brinton’s American Scholar article noted that Harvard had funding for this program for five years, but no further reading lists were issued after 1938 to the best of my knowledge, and January 1939 is the last announcement in The Crimson that I found for the bestowal of the prizes, named for William H. Bliss, though that article indicated that a second round of exams would be conducted that April.

There is much one can say here about this little chapter in U.S. intellectual history: a sort of bridge between Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf of Harvard Classics and the full flowering of American Civilization/American Studies programs after World War II, these exams and reading lists probably have more symbolic significance than they had real influence. But I offer them here for you to peruse the contents of the lists—evaluating canons from the past is always a fun activity for intellectual historians—and in the hopes that other researchers may find them useful!

[1] I can’t let the title of the Crimson article pass without comment: “Unveiling the Untouchable”—the article noted that “with the glorification of [Frankfurter] into a public figure, the immediate Harvard community is bound to suffer, for no one can be a household word and yet remain readily accessible for students or the public to tap the vast fountain of knowledge that is surely there. There was great danger that Professor Frankfurter, with the necessary anonymity that must cloak anyone who enters carefully hooded against the press, both the White House and Hyde Park by the side door, would soon vanish into the clouds and become an ‘informed source close to the President.’” Or, in other words, public service is great and all, but what about Harvard?

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this great post, Andy. My apologies for this slow reply, after getting a positive shout-out from you.

First, I love it that Harvard had a Committee on Extra-Curricular Reading. I wonder if it was making recs for alumni as well? Was it aimed at graduates and promoted for all?

Second, I wonder if it was meant as an answer of U of C’s great books programs, for which Chicago became famous around the same time?

Third, did Harvard also promote *discussion* of the books to be read, among undergrads or others (i.e. alumni)? Did they set up discussion groups?

Fourth, the timing is interesting. Adler’s How to Read a Book appeared in 1940. That book caused a rise in great books reading groups, at first sponsored by U of C’s University College for adults, but then taking on a life of their own at public libraries around the city. I wonder if Adler had heard of Harvard’s effort? I haven’t scanned this section of Adler’s autobio in several years, but I don’t recall him mentioning any Harvard lists as inspiring his own list for the public in the back of his 1940 book. Hmm…

Thanks for this little bit of the history of Harvard, which has now become a provocation for me. – TL

A comment on Tim’s comment (as well as Andy’s post).

First, the Harvard lists mentioned in the post were confined to American history and literature, it seems, whereas the U. of Chicago great books program was wider in scope than that (I assume).

Second, while the lists *might* have been meant as an answer to the U. of C. great books program, my guess would be not. For one thing, these were extra-curricular lists, not a part of the curriculum, so in that sense not an answer to Chicago’s program, which was part of its curriculum.

Harvard’s approach to ‘general education’, which has always differed sharply from the Chicago model in not requiring any particular readings or particular courses of all undergraduates, on the whole I think has not worked particularly well — at least since the 1970s, by which point the gen ed program had become a fairly motley collection of courses of varying quality and focus. The latest version of the gen ed program, in place for about a decade (I forget exactly how long), has just been evaluated by a committee and found wanting. This is off the topic of the post, so I’ll stop there.

p.s. It just occurred to me that Tim must be talking about the U of C great books programs that were aimed at the general reading public, not the great books part of its undergrad curriculum. So I’ll retract the second pt above.