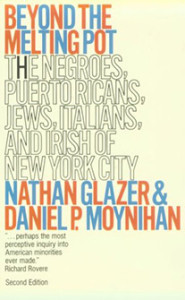

In his book A War for the Soul of America, Andrew Hartman argues that the contribution of neoconservatives to the culture wars is greatly underestimated. Today, I hope to bolster this claim by examining the number of soon-to-be-ubiquitous tropes and arguments made by Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan in the course of their 86-page introduction to the 1970 edition of Beyond the Melting Pot.

First, a quick introduction. Beyond the Melting Pot was a co-authored book by Glazer and Moynihan first published in 1963. Its primary thesis was that ethnicities and the cultural ties and practices based on them still persisted in New York City, which they took to be roughly representative of most urban spaces in America. Yet despite the argument about the persistence of particularity, the book was also concerned with how ethnic identity remained even after certain groups – such as the Italians and the Irish – were incorporated into political power structures through traditional practices and institutions.

The rest of the 1960s, however, dampened their hopes for continued ethnic culture combined with successful political assimilation. The civil rights movement, and especially the radicalization of some segments of black activism, had made the question of race a divisive, hotly contested arena, and several portions of the population – including white radicals – had decided to disregard the usual channels of political lobbying and representation. This was, to put it bluntly and without danger of exaggerating, simply terrifying to Glazer and Moynihan. Consequently, most of the lengthy intro of the 1970 edition concerns itself with either taking jabs at the absolutely irredeemable and unrespectable tactics of black militants, or scolding white radicals and a sensationalist press for legitimizing their claims either by agreeing with them or, much to Glazer’s and Moynihan’s chagrin, reporting on their activities and arguments.

Thus the introduction to this 1970 edition provides historians with an excellent example of how neoconservatives helped create some of the most basic talking points of yes, conservatives, but also, later on, some liberals. However, due to time and length constraints, I’m going to go over these tropes and arguments rather methodically and in list form, so excuse the lack of narrative these will be presented with.

1. Black militants ruined the chance for gently negotiating with whites. Had they been spoken softly to, they would have been much more happy to help out.

A favorite among some liberals even today, this is one of the most-repeated arguments in the book.

Black demands for power “ignored that other groups did have interests, and did have power, and would and could react against militant and arrogant demands, which owed to the black culture of the streets a good deal of their peculiar bite and arrogance. Whatever the effect of this new black style in creating self-satisfaction among those who used it, it did little to reach the other side and create conditions for accommodation.”[1]

“For just as a ‘nigger’ can be made by treating him like a ‘nigger’ and calling him a ‘nigger,’ just as a black can be made by educating him to a new, proud, black image – and this education is carried on in words and images, as well as in deeds – so can racists be made, by calling them racists and treating them like racists. And we have to ask ourselves, as we react to the myriad cases of group conflict in the city, what words shall we use, what images shall we present, with what effect? If a group of housewives insists that it does not want its children bussed to black schools because it fears for the safety of its children, or it does not want blacks bussed in because it fears for the academic quality of the schools, do we denounce this as ‘racism’ or do we recognize that these fears have a base in reality and deal seriously with the issues? When a union insists that it has nothing against blacks but it must protect its jobs for its members and their children, do we deal with those fears directly, or do we denounce them as racists? When a neighborhood insists that it wants to maintain its character and its institutions, do we take this seriously or do we cry racism again?”[2]

2. Moreover, an obsession with racism actually creates racism.

After listing two black politicians to be either granted significant political office or considered for it, they argue that before the rise of black power “It was becoming routine for Negroes to have ‘a place on the slate.’ Only after a decade of intense preoccupation with injustices done black people, with ‘white racism,’ ‘genocide,’ and the rhetoric of social revolution did it become a chancy thing to nominate a black for the least significant of statewide posts.”[3]

3a. The intellectuals, liberal elites, and militant blacks are combining against the average American and the American way.

“In New York a game followed in which there were in essence the five players constituting the groups described in Beyond the Melting Pot and, in addition, an elite Protestant group. The play went something as follows. The Protestants and better-off Jews determined that the Negroes and Puerto Ricans were deserving and in need and, on those grounds, further determined that these needs would be met by concessions of various kinds from the Italians and the Irish (or, generally speaking, from the Catholic players) and the worse-off Jews. The Catholics resisted, and were promptly further judged to be opposed to helping the deserving and needy. On these grounds their traditional rights to govern in New York City because they were so representative of just such groups were taken from them and conferred on the two other players, who had commenced the game and had in the course of it demonstrated that those at the top of the social hierarchy are better able to emphathize with those at the bottom. Whereupon ended a century of experiment with governance by men of the people. Liberalism triumphed and the haute bourgeoisie was back in power.”[4]

“The difficult question we face today is whether black groups that insist – rhetorically or not, who is to tell? – on armed revolution, on the killing of whites, on violence toward every moderate black element, should be tolerated. Even if they are, however, they should not receive public support and encouragement. Intellectuals in New York have done a good deal to encourage and publicize this kind of madness.”[5]

3b. And the media is guilty of the same thing.

“In the 1960’s, the black Invisible Man became the working class and the middle class, people who had been leaders in their communities. They were now pushed aside by young militants, who were supported by white mass media and some white political leaders.”[6]

4. Reverse racism.

Approvingly quoting Michael Lerner: “An extraordinary amount of bigotry on the part of the elite, liberal students goes unexamined. … The violence of the ghetto is patronized as it is ‘understood’ and forgiven; the violence of a Cicero racist convinced that Martin Luther King threatens his lawn and house and powerboat is detested without being understood. Yet the two bigotries are very similar.”[7]

Back to Glazer and Moynihan: “In the course of the 1960’s, the etiquette of race relations changed. It became possible, even, from the point of view of the attackers desirable for blacks to attack and vilify whites in a manner no ethnic group had ever really done since the period of anti-Irish feeling of the 1840’s and 1850’s. This was yet another feature of the Southern pattern of race relations, as against the Northern pattern of ethnic group relations, making its impress on the life of the city. There was, of course, an inversion. The ‘nigger’ speech of the Georgia legislature became the ‘honky’ speech of the Harlem street corner, or the national television studio, complete with threats of violence. In this case, it was the whites who were required to remain silent and impotent in the face of the attack. But the pattern was identical./ The calamity of this development will be obvious. The whites in the North responded much as did the blacks in the South.”[8]

5. Northern innocence.

“The Northern model is quite different. [From the Southern model.] There are many groups. They differ in wealth, power, occupation, values, but in effect an open society prevails for individuals and for groups. Over time a substantial and rough equalization of wealth and power can be hoped for even if not attained, and each group participates sufficiently in the goods and values and social life of a common society so that all can accept the common society as good and fair.”[9]

6. The black community did not know how to do politics correctly; if they had, they would have had a much easier time.

“There was another political failure of the sixties, and this was the failure of Negroes (and Puerto Ricans) to develop and seize the political opportunities that were open to them. It was less clear in 1960-61 than in 1969 how massively Negroes (and Puerto Ricans) abstained from politics, in some of the key ways that counted, for example, voting.”[10]

“To our minds, whether blacks in the end see themselves as ethnic within the American context, or as only black – a distinct race defined only by color, bearing a unique burden through American history – will determine whether race relations in this country is an unending tragedy or in some measure – to the limited measure that anything human can be – moderately successful.”[11]

“The white ethnic groups were familiar with the processes of bureaucratic advancement – how long a time was necessary at one level to reach the next. Many Negroes, excluded from this kind of experience, were not, and were unaware when they made demands for Negroes in high position in various bureaucratic organizations, government and nongovernment, how shocking and immoral these demands appeared to those who had served their time.”[12]

—————————–

Alas, this does not exhaust the list; but I had to stop somewhere, lest the length of this post get out of control.

A final note. In the midst of the section on “The Catholics and the Jews,” Moynihan and Glazer spend several pages expounding on what they perceive to be a rising demonization of Italians in popular culture, arguing that they have been accused of “persistent criminality.” I have absolutely no idea where this idea came from, if anyone else was articulating it at the time, or if it has even the remotest basis in reality. The only evidence they really offer is the popularity of shows and movies about the mob, and Robert Kennedy going after said mob. It is strange, I think, to think books like The Godfather made people dislike Italians – my impression is that it made them incredibly cool, especially, after the movies came out, amongst young people in the black community – but perhaps this is wrong. Any thoughts?[13]

[1] Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italia ns, and Irish of New York City (Second Edition) (Cambridge and London: The M.I.T. Press, 1970), xvii.

[2] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, xl-xli.

[3] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, xxii.

[4] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, lxii-lxiii, emphasis in original.

[5] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, lxxxvii.

[6] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, xliv.

[7] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, lxxiii.

[8] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, lxxiv – lxxv.

[9] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, xxiii.

[10] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, xviii.

[11] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, xl.

[12] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, lv.

[13] Glazer and Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot, lxvi-lxviii.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is such a great piece. I hope we all keep it in mind when it comes time to nominate things for “blog post of year” awards: it is lucid, timely, and strikes a great tonal balance.

I have a kind of stray thought, triggered by your discussion. So much of the anti-communist line in the humanities, beginning at the latest with the formation of the ADA, hinged on the allegation that the CP was dictating lines to activists and artists. The danger of “conspiracy” (as opposed to “heresy”)–in the Hookian formulation–always had something to do with the idea of ideology as a mode of address, and of African American social actors as uniquely open to manipulation (for this, we have white popular culture’s representations of African American subjectivity largely to thank). But here is the very interesting thing: the mode of address adopted by Glazer and Moynihan vis-a-vis black activists could not be more programmatic, absolutist, and manipulative, both in form and content. I suppose that the main takeaway from this would be: liberals and proto-neocons were hypocrites or tended to argue in bad faith (there wouldn’t be anything much new in that charge). But I sense that there is something deeper in the affinity of the disavowed CP ideological command and control model and the assumption of that very model by, eg, Glazer and Moynihan. What do you think?

Kurt, thanks for this really thought-provoking comment! I’m wondering if I could ask you to elaborate here about the parallels you’re seeing; on the one hand, I think there really is something here, but I’m wondering as to what specific similarities you are noticing, so as to not put words in your mouth.

Sure.

I guess what I am trying to tease out is an answer to the question: why does the Glazer/Moynihan text strike us today as so offensive? And the answer would seem to be: because their arrogance in dictating to African Americans the “proper” way of doing politics is so inflated and lacking in self-consciousness.

The reader cannot help but find this idiom at least tacitly racist.

What seems interesting is that the main takeaway from, say, Richard Wright’s contribution to The God That Failed, is that the CP was bad for African Americans because it arrogantly dictated to African Americans the “proper” way to do politics and art; the same may be said of Harold Cruse’s Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. So, the implicit ethical premise––members of a dominant group should not dictate to another group the “proper” way to do anything––underlying the anti-communist critique of the Popular Front is violated rather spectacularly in a text like Beyond the Melting Pot. If there is something deeper in this contradiction than hypocrisy, I don’t know, but I am interested in the idea that there might be…

Thanks Kurt, I’m following you much better now; and yeah, you’re absolutely right. As for if I have any ideas as to whether there is anything more to this than rank hypocrisy, I must confess nothing particularly compelling comes to mind; my only possible thought is that a lot of these neoconservatives were, as we know, former Marxists of various partisan predilections; once they became liberals they need critiqued much of what was “wrong” with Marxism, while nonetheless, as Andrew talks about in his book, retaining a lot of their style and mode of analysis. So it’s also possible that they carried on a tradition of simply seeing black Americans as a means to an end, and not as a distinctly oppressed group that indicated a serious problem with their political perspectives and orthodoxies, with their own insights on how to do politics “properly.” However, that’s pure speculation.

Great post, Robin. This brings me back. The summer before starting graduate school I processed the papers of Michael Novak’s short-lived Ethnic Millions Political Action Committee (EMPAC!) at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. It lasted, I think, from roughly 1974 to 1978, when Novak departed for the American Enterprise Institute. Anyway, EMPAC! (yes, it really has an exclamation point) presents a case study in the kind of politics you dissect here. Novak, as you probably know, was a close ally of Glazer and Moynihan—veering from FDR liberal to neoconservative around the same time.

Specifically, Novak invested a great deal in the concept of “ethnicity” as a way out of “race,” which he saw as divisive. His argument was that race-peddlers–black militants and liberal allies, for Novak–short-circuited democratic debate and discussion, the kind of pluralistic power politics that Novak, Glazer, and Moynihan idolized, for political and cultural ransom: i.e., obey us or risk being branded a racist. Novak greatly resented this logic, on a personal level. The thing about negative white ethnic stereotypes was deeply important to him. He liked to call white ethnics “the new niggers of America,” the words he used to describe the guards at Attica in his review of Tom Wicker’s reporting on the hostage crisis and massacre (Commentary, May 1975). Whereas ethnicity, in Novak’s view, was all-inclusive and more egalitarian. All could claim some unique cultural identity.

EMPAC! was Novak’s attempt to deploy similar ideas as those in Glazer and Moynihan’s book. The organization really does belong to this post-Civil Rights moment when many groups were borrowing or taking inspiration from African American political mobilization. Novak envisioned white ethnic pride as a way to counter an out-of-control, white-guilt-fueled liberalism and also, less explicitly, to restore the traditional balance of power, i.e., with “responsible” people firmly in control of the political process. Novak relished PC culture before it came into its own, calling out people for making Polish jokes, for example. From his EMPAC! correspondence, he appears both genuine and a little cynical, clearly aware of the political capital of claiming personal injury for racial or ethnic bias.

Novak was uncomfortable and ultimately unwilling to address the historic and structural racism that had positioned white ethnics to thrive in urban politics while systematically depriving African Americans of that same opportunity. His celebration of ethnicity was always also about minimizing the damage done by racism—and, consequently, treating racial identity as illegitimate. He therefore was opposed to a racial-justice oriented social policy because it seemed to come at the expense of other groups—namely those he identified with. And so, he dug in. He waved the banner of white ethnic pride. He insisted on white ethnic victimhood. He celebrated the Polish people fighting in the Revolutionary War. Reading his letters at the time, you get the sense that he took Black Power as a personal jab at him and his kind.

Alex, thanks so much for this summary of your research on Novak. Indeed he followed pretty much the same pattern as so many neocons or just grass-root white reactionaries at the time. What’s interesting, of course, is how they both play up the victimization of white ethnics, largely from borrowing from the ways African Americans had critiqued American society, while using those critiques are arguments to stipulate that blacks weren’t nearly the victims they claimed! Hence the irony of someone arguing against racially conscious policy getting very serious about tackling jokes about whites ethnics. I think this goes to yet another illustration of Corey Robin’s argument that the Right is always borrowing from the tactics and modes of the Left that they are reacting against.

Also, it is interesting how much of this “reverse racism” argument has remained, but I think the posture of taking offense has been drastically reduced as a rhetorical move. I’m thinking of all while we still constantly hear references to the mostly-mythical “Irish Need Not Apply” signs, what we hear a lot less of is the open taking of offense at white ethnic jokes — indeed, as we all learned from Gran Torino, white people often point to their *lack* of sensitivity about these things as a model for how other minorities ought to be doing things; it’s not big deal if I call him a pollack!, he’s not an overly-sensitive baby, etc. (Of course Jews being the one major exception to this, for good reason.) I wonder why that became less common; perhaps it just wasn’t ever fully believable, and it definitely failed, in any case, to privilege the category of ethnicity over that of race in terms of the dynamics of American politics. Anyway, so much to chew on!

(And oh, the explanation mark is hilarious. Love it!)

Re: Italian-Americans. The public discussion which presumably accompanied passage of the RICO Act in 1970 which was focused on the Mafia may account for part of Glazer/Moynihan’s concern with the Italian image. Jimmy Hoffa was still living and a prime weapon for conservatives to attack the unions. I also think by 1970 the theory linking the Mafia to JFK’s assassination was also floating around.

Puzo’s novel was just published in 1969 and the movie was yet to come. It would be interesting to know what Glazer and Moynihan thought of it.

re. mostly-mythical “Irish Need Not Apply”

http://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/new-york-times-finds-no-irish-need-apply-in-classified-ads-1.2345597

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/08/insider/1854-no-irish-need-apply.html

perhaps a small point and correction, yet I think an important and disconcerting one. As yo have made the valid argument elsewhere on the blog, empirical evidence is critical to the academic practice of history. It is especially so in the attempt to clearly demarcate the power boundaries of identity that shaped and defined what it meant to be, and who was allowed to be (culturally speaking ) an American. I dont want to wade into theory or to speak, anachronistically of Intersectionality, However I do think historically delineating between victim and villain is not as easy as I once assumed, and if the process devolves into a morality tale, it can blind scholars to larger structural forces that can better Illuminate the past and perhaps issues of today. A thirst for Justice in the present ( a righteous thirst that should be quenched as often as possible) can not obliterate nuance from the discipline or blind us to the distinct possibility of hubris and and Clericalism within the profession. Such ailments can do as much if not more harm to Clios record as can popular preJudice. That being said thank you for your work on this blog Dr. Averbeck, I very often find it engaging and stimulating. I know it is was some time ago but I especially appreciated yor post on mental illness. It was a deeply compassionate, empathetic and one of the more moving pieces of writing id read on the topic in some time. The epitome of a public intellectuals work.