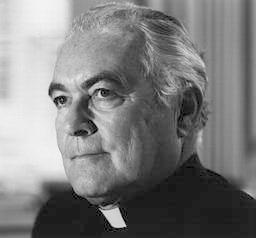

I began by forwarding a key distinction and discussing how I became acquainted with Hesburgh as a historical figure in higher education (i.e. his support for a great books program at the University of Notre Dame). But I neglected to emphasize a key reason, however, for thinking historically about Hesburgh as a Catholic intellectual. The goal was to underscore his intellectualism as opposed to simply recognizing him as a long-serving, popular, and prominent university president—i.e. as an administrator, in a word.

Last week I did note that Hesburgh was “more than a university president.” But I didn’t emphasize that a president can and perhaps should be more than that. I also noted that this was a “compliment, but partially by way of contrast.” I made a historical contrast in relation to midcentury Catholic intellectual life, but I should have also contrasted Hesburgh’s life and legacy to present-day university presidents. The conversation about university presidents today centers on their role as executives—i.e. their pay (and here), better marketing and increased prestige, building new buildings, overseeing tuition increases, and their role in the overall general increase in administrators. Presidents today are known for creating programs and expanding facilities, not necessarily for leading the way intellectually.

I don’t yearn, nostalgically, for a false past of presidents as scholars. But I think Hesburgh was different in that he most certainly approached his presidency as a thinker. I don’t mean to suggest that he was some kind of higher education saint. Rather, his concerns were about Catholic intellectual life and about the nation’s direction broadly. He was a public intellectual while also being a university president. In his historical context, Hesburgh displayed a balance between his identities as a Catholic and as a liberal-leaning public intellectual that transcended his role as university president and the general run of intellectual Catholics in the United States.

Notes on Hesburgh’s Intellectual Biography

You can find more on Hesburgh’s life at a remembrance page set up by the University of Notre Dame, as well as in a biography of Hesburgh, authored by Michael O’Brien and published in 1998. But here’s a rough and abbreviated recap—with an emphasis on his intellectual output and development: He was born in 1917 in Syracuse, New York. Hesburgh attended Notre Dame and Gregorian University in Rome, completing a bachelors in philosophy in 1939.

In 1943 he was ordained at Notre Dame as a priest of the Congregation of Holy Cross, at the age of 26. Hesburgh earned a doctorate in sacred theology from Catholic University of America in 1945.From the dissertation Hesburgh produced a book, The Theology of Catholic Action (1946). He went on to write five other books: God and the World of Man (1950), The Humane Imperative: A Challenge for the Year 2000 (1974), The Hesburgh Papers: Higher Values in Higher Education (1979), God, Country, Notre Dame (with Jerry Reedy, 1990), and Travels with Ted and Ned (also with Jerry Reedy, 1992). On the last, here’s how The New York Times described its inspiration: “He retired from Notre Dame in 1987. Soon after stepping down, he and the Rev. Edmund P. “Ned” Joyce, who was Notre Dame’s executive vice president under Father Hesburgh, took a year to travel across the country in a recreational vehicle.”

Although Hesburgh’s thought is also present in his numerous articles, addresses, speeches and essays (205 from 1940-1988, said Michael O’Brien in 1988), two essay collections bear on his intellectual interests and role as a Catholic public intellectual:  Hesburgh and Louis J. Halle (eds.), Foreign Policy and Morality: Framework for a Moral Audit (1979) and Hesburgh (ed.), The Challenge and Promise of a Catholic University (1994). Aside: O’Brien noted that Hesburgh had also produced seventeen unpublished diaries (totaling over 2200 pages) from 1973 to 1989.

Hesburgh and Louis J. Halle (eds.), Foreign Policy and Morality: Framework for a Moral Audit (1979) and Hesburgh (ed.), The Challenge and Promise of a Catholic University (1994). Aside: O’Brien noted that Hesburgh had also produced seventeen unpublished diaries (totaling over 2200 pages) from 1973 to 1989.

Hesburgh resigned as president on June 1, 1987.[1]

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

In DePalma’s NYT obituary he relays the following about Hesburgh’s participation in the Civil Rights Commission:

“Mr. Eisenhower made him a charter member of the Commission on Civil Rights in 1957. He became its chairman in 1969. Under his leadership the commission criticized President Richard M. Nixon for not directing his administration to enforce civil rights laws. During Mr. Nixon’s re-election campaign, in 1972, Father Hesburgh blasted the president’s opposition to school busing, calling it “the most phony issue in the country.” Mr. Nixon demanded his resignation a few weeks after the election.” [2]

Created by the Civil Rights Act of 1957, other members of the Commission during Hesburgh’s tenure included (from Wikipedia): John A. Hannah, President of Michigan State University; Robert Storey, Dean of the Southern Methodist University Law School; John Stewart Battle, former governor of Virginia; Ernest Wilkins, a Department of Labor attorney; and Doyle E. Carlton, former governor of Florida.

The Commission as of 1954 (from Michigan State University’s President’s page — http://president.msu.edu/from-the-presidents-desk/2015/honoring-father-hesburgh.html)

Tasks of the Commission included gathering facts (i.e. holding hearings) on topics such as voter registration and elections in Alabama, desegregation after the Brown decision, and housing discrimination in major urban areas.

For his work on the commission, DePalma relays that “President Lyndon B. Johnson…awarded [Hesburgh] the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964.” That said, Hesburgh did, in fact, leave the Commission in 1972. His work there earned him consideration, from George McGovern, as a v.p./running mate in 1972. [3]

Next week I’ll move the story back a bit, chronologically, to demonstrate Hesburgh’s intellectual leadership in higher education and on campus. I’ll discuss the Land O’Lakes Statement, campus unrest at Notre Dame in 1969, and his involvement with the Knight Commission.

——————————————————–

Notes

[1] Anthony DePalma, “Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, Influential Ex-President of Notre Dame, Dies at 97,” The New York Times, February 27, 2015; “Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., 1917 – 2015,” University of Notre Dame, http://hesburgh.nd.edu/, accessed March 18, 2015; Michael O’Brien, Hesburgh: A Biography (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1998)

[2] DePalma

[3] DePalma; Pierre Salinger, “Four Blows That Crippled McGovern’s Campaign,” LIFE (Dec. 29, 1972), 73.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Interesting. I either didn’t know or had forgotten that Hesburgh had been considered as McGovern’s running mate. (But then, that ill-fated, alas, campaign ran through a large number of vice-presidential possibilities, probably both before and after the Eagleton episode.)

McGovern was forced into “considering” lots of candidates—because so many turned him down. I like what the anecdote indicates about Hesburgh’s own integration of Catholicism and politics. – TL