Today marks the forty-seventh anniversary of the Orangeburg Massacre. On February 8, 1968, 3 students were killed and many more were injured during a clash with police in Orangeburg, South Carolina. All the students killed and injured were African American, individuals who attended the local Historically Black institution South Carolina State College (now University). It’s a moment that, frankly, deserves to be talked about more. Today I’d like to place it in the context of late 1960s discourse about civil rights, black power, and the position of African Americans in U.S. society.

The protests that resulted in the Orangeburg Massacre were over the segregation of a bowling alley in Orangeburg. But the very fact of the incident should serve as a reminder that the struggle for black political, social, and economic power in the Deep South was far from over. The historical narrative of the 1960s often goes as thus: African Americans protest Jim Crow segregation in Deep South. This culminates with the 1963 March on Washington, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Sure, everything’s not peachy in the South, but the action has moved north by late 1965. Black Power comes on the scene and…fin.

Of course many of us know this wasn’t the case. Consider that the phrase “Black Power” was invoked by Stokely Carmichael at a June 1966 rally…in Mississippi. But events like the Orangeburg Massacre of 1968, and the Jackson State murders of 1970 (in which black students were killed for protesting the invasion of Cambodia around the same time as the Kent State Massacre) remind us of the world American intellectuals, black and white, lived in during the late 1960s. It was an era not just of long, hot summers in Northern cities, but a time period of continued pushing by African American activists against the Southern status quo.

Right now, as South Carolina State University and other locations across South Carolina commemorate the 1968 event, we as intellectual historians should consider the following question: how do some moments become better remembered than others? Was the Orangeburg Massacre forgotten simply because it was but one tragic moments in a year full of them? That may be the case. A more practical matter to consider is that the shootings occurred at night, producing little in the way of photos or footage of the event. Fears of black militants also mitigated any potential sympathy for the protestors. It’s also worth considering how the events in Orangeburg upend our understanding of the history of race relations in the United States. The Orangeburg incident, occurring as it did during the height of debates about law and order, Vietnam, and poverty, also remind us that the South was still the site of arguments about all these issues.

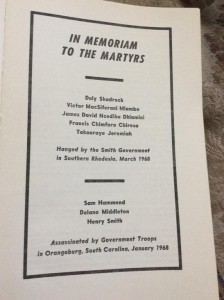

Finally, I wish to consider the ways in which African American activists viewed the incident. Freedomways magazine, a leading voice of the African American Left from the 1960s to the 1980s, highlighted the incident in an advertisement in their Spring 1968 issue. It was fitting that their tribute to the Orangeburg Massacre was coupled with the names of five individuals executed by the government of Ian Smith in Rhodesia. For the Freedomways editors, both were examples of local phases of a world problem. In what must have been a trying time for the Freedomways

editorial staff, the Spring 1968 issue also included a tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr., who himself had an essay in the magazine that was a speech he gave in tribute to W.E.B. Dubois that February on what would have been his one hundredth birthday.

What societies, and elements of society, choose to remember matters—they symbolize what kinds of historical narratives matter to people. Just as importantly, what we choose to forget also indicates what kind of society we are. Don’t forget the Orangeburg Three.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks so much for this really important corrective, Robert. It reminds of Vesla Weaver’s “frontlash” thesis on how elite racial conservatives–nominally a defeated cohort in the wake of a series of major civil rights victories–regrouped in the mid-’60s under the banner of “law and order” to begin rolling back the struggle for racial equality. The forgetting of Organeburg seems like the brutal outcome of this elite countermobilization to equate any social protest for racial egalitarianism with crime in the streets.

I’d like to echo Kit’s thoughts about how great this piece is, and to commend your writing here as a terrific example of how to do the work of public history.

Thanks for this, Robert! I was of course aware of the Kent State and Jackson State massacres, but not this one—until your post. Am I right in assuming the Orangeburg police were all white? And were the killings noted in Ebony, Jet, or the Chicago Defender? I ask because I wonder about the publication of reactions by prominent black thinkers and writers.

PS: What’s worse is that I recently reviewed a book on the Kent State massacre (*Democratic Narrative, History, and Memory*, 2012), and it mentioned Jackson State but missed Orangeburg.

Nice job, Robert. I’ve often wondered why the Orangeburg Massacre failed to receive the public attention it so obviously warranted. The whirlwind of major national events before and after the Orangeburg Massacre (King, RFK assassinations; Democratic Party meltdown in Chicago; Kent State massacre; and the Tet Offensive) helped to minimize the press coverage it received. The lack of national media coverage was also largely due to the Governor’s explanation of the tragedy, its nearly unanimous acceptance as fact by SC media and the majority of the state’s white citizens; and the FBI cover-up/Sellers kangaroo trial that followed. Lastly, Dr. Lacy is correct to point us in the direction of the media. To what extent were certain media figures involved in COINTELPRO and its local affiliate programs? If journalism is the “rough draft of history,” then historians should pay closer attention to those who held the eraser when events like this occurred.

Thanks from me as well, Robert; I also was not aware of this incident. That captures so well one of the major problems with the way the civil rights movement has been remembered and remains so powerful in the country’s racial politics; usually the public only holds up those who appear 100 percent moderate and committed to “the American way” as worthy of being mourned if killed by racist violence; as though #blacklivesmatter needs to be updated to #radicalblacklivesmatter.