I recently began reading sociologist Barry Schwartz’s 2008 Abraham Lincoln in the Post-Heroic Era: History and Memory in Late Twentieth-Century America. It is an argumentative and, to me, frustrating book which waffles deliberately on the question of whether what he refers to as a “weakening faith in human greatness” is a good or bad thing. “The moral and social leveling supporting the most congenial society in history, a society largely free of ethnic and racial hatred, inclusive of all peoples and solicitous of their rights, is precisely the kind of society in which great men and women and their achievements count for less, while the victimized, wounded, handicapped, and oppressed count for more than ever before,” he writes, and, later, “’The fading of the great man is part of a new moral order at once liberating and just, alienating and shallow” (8, 19). My suspicions are that this even-handedness is specious, that “alienating and shallow” expresses Schwartz’s deeper feelings, feelings which, as we know from recent eructations by eminent scholars, are becoming increasingly easy to state without the coy impartiality.

The question of the “post-heroic” or, as another recent book has it, “the end of greatness,” is, I think, little theorized and even less challenged among historians in large part because few historians any longer openly use the discourse of the heroic. Historians seldom respond to these insinuations that our world has lost something vital with our passing into a post-heroic era. Many historians tend to think that the Carlylean Great Man theory is essentially extinct. We understand that there is a cult of the Founders that requires our scholarly attention, but we regard the category of Great Men as an antique not worth the dusting off to disagree with.

But there is also a key ambiguity at the center of the term “post-heroic” which those who bemoan our society’s passage into the “post-heroic” are better off not resolving and which we ignore to our disadvantage. There is on the one hand a sense that, in a “post-heroic” age, there are no longer any Great Men (or women, when they’re remembered); that is, no one can rise to true greatness, to heroism in a world that, as Schwartz contends, celebrates victimhood instead. But there is another side as well to the term which suggests not that no one can rise to greatness, but that certain forces prevent broad public recognition of the Great Men who might still walk among us, unappreciated.

What this ambiguity permits is a subtle but devastating move: while under the cover of a social diagnosis—the “post-heroic age”—a direct attribution of blame is bruited: “there is nothing wrong with society, in fact, which wants heroes, wants Great Men,” it intimates. “It is only the [fill-in-the-blank: liberal elites, ivory tower intellectuals, postmodernists, multiculturalists] who enforce a false equality or tarnish good men and women with their accusations of racism, sexism, and so forth. They won’t let us have heroes; they just tear them down.” Or as William Bennett puts it in an introduction to his 2011 The Book of Man: Readings on the Path to Manhood:

In a recent survey of twelve hundred junior high school children, the most popular response to the question “Who is your hero?” was “None.” Nobody. Other answers far down the line in this and other polls have revealed the devaluation of the hero, at least. Students today cite rock musicians, Evel Knievel, and the bionic man and woman. This suggests—and my own informal poll and the reports of friends of mine who are teachers have confirmed my suspicion—that heroes are out of fashion. For some reason, perhaps for no reason, many of us think it is not proper to have heroes; or worse, that there aren’t any—or only shabby ones.[1]

This nescient or plain passive-aggressive note is characteristic: we all know precisely what Bennett imagines are the reasons behind this “devaluation of the hero,” and it is in the preterition of it that the lesson is taught: they (the postmodernists, the feminists, et al.) have stolen our innate reverence for heroes, have fooled us into believing we shouldn’t have them.

This devious little turn shifts the field of battle from the heroic and post-heroic to the question of what Carlyle called “hero-worship,” but which is more often described today as a craving for stories of heroism. It is the impulse that we are being told is driving the extraordinary box office success of the film American Sniper: people want to admire heroes, they want to be reassured that the world is not leveled, that heroes still walk amongst us and merit our worship.

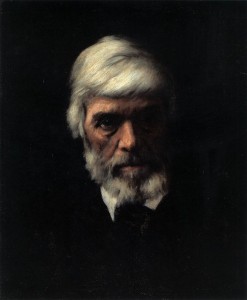

“Hero-worship endures forever while man endures,” Carlyle wrote. “We all love great men; love, venerate and bow down submissive before great men: nay can we honestly bow down to anything else? Ah, does not every true man feel that he is himself made higher by doing reverence to what is really above him? No nobler or more blessed feeling dwells in man’s heart.”

I am not sure that I have ever read a direct response by a historian to this kind of thinking, not in the way that Butterfield’s Whig Interpretation of History

directly tackled, for all its many faults, questions of teleology and assumptions of inevitable progress, or the way that a host of studies have excoriated the stadialism of vulgar Marxism. Social history, we might agree, is an oblique answer to Carlyle, but an outright rebuttal of Carlyle’s assertion that “we all love great men”—where is that?

In monographs, in lectures, certainly in graduate school classrooms, we hear “whiggish” and “teleological” as still active terms of reproach; we worry deeply and sincerely about the form of the narratives we tell, the way the arc of our stories bends tidily around adverse evidence of progress or improvement, obscuring the power of reaction and the potential for true defeat. We correctly cherish contingency both as the watchword of lost alternatives to the present and as an admonition against believing that fortune favors the good; it helps us maintain that Gramscian equipoise: pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.

But these are ideals about narrative, and when a Gordon Wood writes a Weekly Standard piece telling us that we are doing it wrong, we go to battle with him over narrative and over basically narratological meta-issues like presentism (which Eran laid out excellently). But aren’t we missing the other charge running through critiques like Wood’s, or Bennett’s, or Schwartz’s? We have picked the wrong protagonists, they say. We have chosen to honor not Odysseus but Thersites, not Alcibiades but the Melians, the “victimized, wounded, handicapped, and oppressed.”[2]

We choose, I think, not to defend that decision and say, yes, these are our protagonists, and they challenge traditional notions of heroism and that is a good thing. We avoid saying directly that no, there is no such thing as an innate desire to abase oneself before Great Men, there is no inchoate craving for hero-worship. Perhaps we are more conflicted about these statements than we are about the impossibility of reaching objective truth or shedding our politics at the threshold of history-writing. But this ground—a debate about heroes and hero-worship—is also the one that figures like Gordon Wood are parading around on. We ought to meet them there.

[1] Bennett, The Book of Man: Readings on the Path to Manhood (Nashville: Nelson Books, 2011), xxvii, my emphasis. The references to Knievel and the bionic man and woman betray that, as Bennett confesses, this part of the book was written “forty years ago.” Cut and paste.

[2] “In other words, unless the Indians became the main characters in his story, Bailyn couldn’t win,” Wood says. And historians from Vine Deloria to Ned Blackhawk say, “Yes—that is the point.”

20 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

What a beautifully written, generative post, Andy.

On challenging Carlyle…

Perhaps there’s a kind of hero worship that deeply structures the historical profession, both as something we accede to and something we struggle against. Our great men and women are those who have triumphed in the agon of writing history, who have led the field, who have changed the field. Historians’ heroes are other historians. We do our hero worship via historiography, so that every reconceptualization of the past entails a reconstruction of the pantheon. But of course the continuous reconstruction of the historiographic pantheon as an open-ended project that goes in tandem with the continuous re-envisioning of the past, so that if we are bowed down it is only because we are all carting around the building materials for this unending renovation project — well, that itself is our rebuttal to Carlyle. And, I think, to Wood, with his anxiety that a certain great historian is not as honored these days as he should be.

Thanks Andy, this is very interesting and reminded me of one of the interesting ironies of Wood’s piece–that Bernard Bailyn and to a certain extent Wood when he was younger do not seem to buy into the great men theme. Yes, they both studied the ideas of elite men, but both seemed to regard them as rather paranoid and perhaps even delusional at times. Indeed, Bailyn was primarily interested in empathizing with men caught in watershed moments, as they sought to make sense of such transformations. His book on Thomas Hutchinson is the best example, I think, of that theme in his work.

On that note, it’s also quite interesting that Wood alluded to Bailyn’s reverence for Ronald Syme, who perhaps more than any other historian helped us do away with the great man paradigm in history when he wrote his famous “The Roman Revolution”, which undermined the notion that Julius Caesar was an exceptional human being that transcended his historical circumstances.

And even Wood’s “Radicalism of the American Revolution” was not so much interested in valorizing the class of gentlemen that wrote and signed the Constitution, but with the common men that inherited it.

It was only later, I think, that Wood started to cherish great men left and right and started maligning anyone who tarnished the names of the founding fathers.

the other day i was looking at Ernst Cassirer’s *The Myth of the State*, I think his last book, immediately post-ww2, all about coming to terms with these events. he has a chapter on Carlyle, basically discussing the extent to which Carlyle’s notion of hero-worship was the most important ideological component of what eventually became the Hitler cult. this was apparently a not-uncommon way of understanding Carlyle’s importance in the 1930s and 40s. So this maybe has something to do with how we think about hero-worship today, or at least an inherited tendency to avoid taking the idea seriously over the last few generations?

also, i can’t imagine that the idea of the hero is really very easy to retain in any substantive sense after psychoanalysis?

One thing (among others) I’ve learned from Andy’s posts is an appreciation for the word “nescient,” which doesn’t seem to be used all that much these days (though it’s obviously a perfectly good word) — I looked it up (two senses basically: “ignorant” or “agnostic”). The online OED gives this among other examples of its use, from a Dec. 2000 piece in The Independent on Sunday: “George W Bush, the smirking and nescient scion of the most mediocre political dynasty in American history.”

Ok, that has nothing to do w/ the substance of the post, but hey… it’s the blogosphere.

I agree that Andy’s use of “nescient” is awesome.

Well, is Alcibiades really a “hero” in Thucydides? A curious juxtaposition with the Melians–and it raises a larger question of what exactly it means to “challenge traditional notions of heroism and that is a good thing”. I do not think Carlyle can stand in for the complicated conceptions of what a hero is and is not that existed before social historians arrived on the scene–and I’m not sure a debate framed thus would be all that useful.

Thanks, everyone, for these great comments. I’ll take them up in reverse order.

Wayne, I’m not sure precisely what you mean by the last part–that there were multiple definitions of the hero? or that Carlyle’s wasn’t influential?–but as for Alcibiades, the judgments about him are, as I’m sure you know, notoriously divided. I’m not sure if by “is Alcibiades really a ‘hero’ in Thucydides?” you are asking if Thucydides considers him a hero or if we should consider the character from Thucydides a hero. Nietzsche, for what it’s worth, has a noteworthy passage alluding to him in Beyond Good and Evil, and it’s approximately that kind of characterization that I had in mind here.

Thanks, Louis–I enjoyed that OED example a lot!

Eric, I’ll take a look at the Cassirer (I had seen a citation to it but hadn’t rounded it up), but my feeling is that it would be odd for Carlyle to go into eclipse alone when so many other thinkers and artists were likewise identified as “roots of Nazism,” and yet were (and are) read seriously and studied widely. Nor was this argument undisputed at the time. The drama critic Eric Bentley, in fact, wrote a book in 1944 called A Century of Hero-Worship investigating just this problem, but emphatically rejected a linear or uninterrupted relation between Carlyle and Hitlerism. Bentley’s argument is a little muddled and not exceptionally helpful or acute, but the argument against the notion that Carlyle was a forerunner to Nazism was certainly out there even during the war.

Eran, Like Eric, you’re sending me to the stacks! I haven’t read Syme–and given the thickness of The Roman Revolution likely won’t be able to in any depth–but it seems to me that “an exceptional human being that transcended his historical circumstances” isn’t precisely what Carlyle means by a hero or a Great Man. In fact, Carlyle is really one of the most thoroughgoing historicists of the Victorians: his Great Men do not transcend their moment but rather define it, concentrate or distill it and shape it around themselves. I’m not sure if that’s different from what you (or Syme) are saying–I need to read at least a little of Syme before saying more! And as for Bailyn and Wood, I think you’re absolutely right to point to the strange arc they–or rather Wood–have taken to get to this point.

L.D., I think there are definitely historians who look at the profession the way that you are describing here–which I take to be a sort of Harold Bloom-like anxiety of influence or strong misreading situation? But I feel that what is missing is a sense of reverence for one’s authorities (much less for one’s elders), and it is missing both in the warm admiration we have for our models and in the aggravation we have for the icons we set out to smash. I feel that in most monographs I read, revision is a foregone conclusion, all in a day’s work: not an agon. There are fields where that is not true–the history of the U.S. West, for instance, has a relationship with Frederick Jackson Turner worthy of a country song. But I guess I find less drama in the process of revision or renovation than I do diligence. Not that I’m upholding diligence over drama (necessarily)!

Andy, I’m sorry if I’m sending you to the stacks again, but for what it’s worth, I think that it’s best to read Syme in conjunction with Theodore Mommsen, who wrote almost a century earlier and against whom to a large extend I believe Syme wrote. Mommsen thought the Julius Caesar was the Bee’s Knees and wrote history with what I recall might be regarded as a similar reverence for great men in history as that of his contemporary Carlyle. For Mommsen Roman history was all about how great Caesar was while all the rest of the characters around him, Cato, Cicero, and even Pompey, kind of sucked. From what I recall, and granted I read this stuff ten years ago, Mommsen thought that Caesar’s greatness was his almost inhuman capacity to imagine new possibilities for the Roman Empire and to bring them about with the force of his conviction and will.

Oh no, I’m really excited to page through Syme and now Mommsen–thank you for pointing me to them! Believe me, I never mind being sent to the stacks!

Ah, Andy, thanks for your reply.

I don’t think I was very clear in my comment — this comes of w.b.c. (writing before coffee).

I meant the “agon” as a contest between the historian and “the past,” or maybe the historian and the blank page, not between historian and historian. So, our champions are the ones who have gotten into the arena and managed to wrest a coherent and illuminating narrative out of the inchoate mass and mess of “the past” and its detritus. We rightly admire and esteem those historians who have managed to explain something in a way that improves upon/enlarges our grasp of the matter at hand. So the historians who have managed to do that end up as “heroes” in historiography — if I can get away with the metaphor of historiography (or a “review of the literature”) as something like a Homeric roll call of the Greeks arrayed for battle.

What historians (taken as a whole) resist — through, as you point out, the revisionism that is a matter of course in our work — is any notion that this list is unchanging, that this “canon” is closed, that the last, best answer is sufficient to put an end to further questions. But I think that individual historians may become devotees of one particular explanatory scheme or another, one particular set of answers, and also perhaps one particular set of problems. So, when the field seems to have shifted to different concerns or questions, that shift can look like an abandonment of something (or someone?) worthy of continued regard. But we can’t be carrying a torch (a votive candle?) for the former explanation, or linger long before it, because we always have a new battle on our hands, turning “the past” into “history” on the damn. blank. page.

That’s what I was trying to get at. But I wasn’t very clear on that.

Thanks, L.D.–I think it has everything to do with the ambiguity of the word “historiography!” I took it in one direction, and I think you were going in a different one. Novick’s little disquisition on this problem at the beginning of That Noble Dream, IIRC, might come in handy sorting us out! But I definitely agree with you, and thank you for clarifying.

Thanks for an interesting post Andy. Just as a counter instance: Linda Gordon did choose to write a book about the history of domestic abuse entitled “Heroes of Their Own Lives,” and it’s not clear to me that the anti-heroic impulse goes hand in hand with progressivism. Emerson’s response to Carlyle was “Representative Men,” and the nineteenth-century notion of “representative” has an entirely different valence from Carlyle–instead of submission to the Greatness of the Hero, the politics run the other way–the “Great Man” embodies and represents the elements of the people and the age–he stands, not in contrast to the masses, but as an expression of the individual persons exemplified–as in a political theory of representation in a republic. So Progressives and those on the left have embraced various culture heroes–e.g. Martin Luther King, Eugene Debs, Frederick Douglass–who embody the will of the dispossessed and marginalized.

The debate, such as it is, over the Great Man Theory of History (which I agree is not a live debate at all) is also a debate about agency vs. determinism (which is a live debate). Sidney Hook, arguing against forms of structural determinism and for the contingent role of individual agency in the 1940s, saw a commitment to Heroes in history as a pragmatic (and perhaps democratic) alternative to forms of Marxian determinist thought, for instance. What I guess I’m suggesting here is that looked at from one angle, the focus on Heroes is an anti-democratic and elitist vision; from another, it represents an expansion of freedom and collective fulfillment against the impersonalism of social forces.

Dan, your post echoes my thoughts in this regard. I am particularly struck by your reference to Sidney Hook, I didn’t know that he invoked heroism positively in his work. In what text(s) does he do this and what other texts engage with the conundrum of anti-heroism versus individual agency? This discussion of course harks back to the 19th century, as you suggest yourself by alluding to Emerson–it reminds me too of Romantic and post-Romantic debates about social movements, which connect with the rise of so-called utopian socialism, anarchism, and of course Marxist thought.

Yes, it was The Hero in History (1943), as Andy notes below. Interestingly, this appeared the same year as Hook’s well known “The New Failure of Nerve,” in Partisan Review–in which he takes on all forms of absolutism and submission to established truths as a cowardly “theological” retreat, and embraces a critical and skeptical commitment to science, contingency, and revisionary consciousness as elemental to human freedom. So he embraced the idea of the Hero at the very moment that he rejected the ethic of submission to a greater power that transcends critical reason.

I’m looking forward to Andy’s further posts on this topic!

This is a question I think a lot about from the perspective of minority politics in the U.S.: how do we also reproduce Carlyle’s romantic theory of “hero-worship” in order to construct inspirational models for peoples of color, models that are not fully visible or are represented in deeply reductive ways in the mainstream eye. For instance, with the celebration of the birthday of Malcolm X, one sees, as Ilyasah Shabazz’s article in the NYT today does, a sacralization of the historical character, whose invocation seemingly can offer a pedagogy for the oppressed in the contemporary era. One can see this also in the debates about Selma and how in centering on the figure of MLK it neglects the importance of the broader social and political communities–from SNIC to the citizens of Selma–that were central in the struggle for racial equality.

What perhaps should also be discussed along with the issue of “the great men theory,” is the question of leadership, the symbolic figure of the leader. This applies to what L.D. says about our “heroes” and “leaders” within our disciplines, as well as other cultural, social, and political formations. My thoughts are not very clear on this matter, but I am always reminded of Freud’s writings on group psychology, the role of transference, and the leader as “ego ideal.” Also, I think of discussions of leadership in grass roots activism that come from the ideals of participatory democracy and anarchism–which can be seen in the “low ego / high impact” discourse:

http://www.stproject.org/from-the-field/blacklivesmatter-lessons/

And at the same time we have the common mainstream complaint of “we need more leaders, better leaders”.

In the end, I am not so sure about the diagnosis offered in Bennett’s book. What can we make then of the proliferation of both fictional and historical fllms centered around a heroic figure? These icons are alive and well, what has happened is a multiplication, or better, a fragmentation “the hero worship,” which of course would unsettle conservatives who desire a limited pantheon of heroic dead white men (or “whitened” black men, as the conservative reduction of MLK to his “I have a dream” exemplifies).

Dan and Kahlil,

Thank you so much for your comments–they point me in exceptionally fruitful directions for further work.

The text I think Dan is referring to is 1943’s The Hero in History. I haven’t read it yet (I’m working through a number of books from this era, like Dixon Wecter’s The Hero in American History (1941) and Gerald W. Johnson’s American Heroes and Hero-Worship (1943). In addition to the Bentley book noted above, and Matthiessen’s treatment of Emerson’s Representative Men in American Renaissance (1941), there’s quite a lot out there from this period! I’ll be following up on it further in subsequent posts–especially on Emerson.

Briefly, though, my take is that, just as scholars periodically lose sight of the tremendous influence of Emerson on Nietzsche (Stanley Cavell: “No matter how many people tell you the connection exists, you forget it, and you can’t believe it, and not until you begin to have both voices in your ears do you recognize what a transfiguration of an Emerson sentence sounds like when Nietzsche rewrites it”), Emerson scholars have tended for a long time to ignore the Carlyle relationship. That’s part of a more general current disregard for (or ignorance of) Carlyle’s influence and significance, but is, I believe, particularly acute in Emerson’s case. This in turn has quite large effects on our interpretation of the interrelations between heroes, hero-worship, and democracy as they emerge in Emerson’s thought and later American social thought (for example, in James). But that’s an argument I’ll need more space to flesh out than in a comment–sorry to defer to a sequel!

Excellent, thanks Andy! The influence of Carlyle also had rammifications beyond the Anglo American tradition: José Martí, for example, quoted him often: he considered him a “Shakespearean” writer, appropriating the great men theory of history unto the Latin American context. It would also be interesting, as Dan suggests, to trace a Carlylean genealogy in African American and Latino culture.

I’m coming late to the party, so I’ll just chime in with a running commentary on bibliography not mentioned thus far: Carlyle’s theory of the hero was well-known in the 19th century: it stands behind Walt Whitman’s motive in writing “Democratic Vistas” (1871), a polemical document written as a rejoinder to Carlyle’s “Shooting Niagara” and focusing on many of the same issues regarding individualism vs. egalitarianism taken up more famously in J.S. Mill’s “On Liberty” (1859). Mill’s third chapter on “Individuality” is also a kind of meditation on Carlyle’s idea of the hero–it is an effort to defend society’s need for aspirational personal qualities (“greatness”) without the mystical, quasi-fascist ideas of leadership that Carlyle sometimes promoted (and let us remember that Emerson celebrates martial figures like Napoleon, too). As Dan Wickberg pointed out, this debate often touches on issues of agency vs. determinism; in the 19th c., in addition to Marx, the main figure on the side of determinism was Herbert Spencer. William James wrote against Spencer’s position in “Great Men and Their Environment” in the 1890s, I think (the essay is in Vol. 1 of the Library of America editions). The debate picks up again around WWII, as Andy notes above (with some books on the “hero” from the early 1940s of which I was unaware!). I would add one more document to this list: Wallace Stevens’ poem, “Examination of the Hero in a Time of War” (1942). (Full disclosure: I have written an essay on this subject that situates Stevens in the context of 19th century intellectual debates about heroes and democracy. I’d be happy to distribute a .pdf to interested parties if they are not able to reach the essay via this link): http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/essays/77411943/everyday-nobility-stevens-paradoxes-democratic-heroism

Patrick,

Thank you so much for these references, and for the link to your great article–really enjoyed reading it. It’s been years since I read Mill’s On Liberty, so thank you in particular for the pointer to the chapter on individuality. I will have much more to say about Emerson and his representative men next week–I hope!